At the same time, local educators training the next generation of nurses said programming was temporarily paused, already-limited capacities in clinical programs became even more restrictive and graduations were delayed.

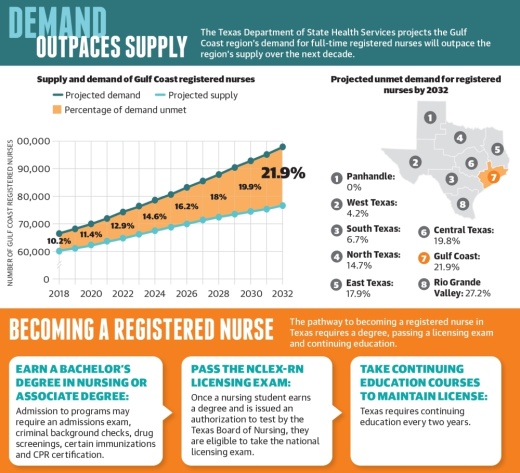

But hospitals across the state have faced nursing shortages since long before the pandemic, health care officials said. The Texas Department of State Health Services projects the Gulf Coast region will have a deficit of 21,400 registered nurses by 2032 as the growing demand continues to outweigh supply.

“Health care workforce shortages existed before the pandemic. We didn’t have enough doctors; we didn’t have enough nurses, and the pandemic has definitely exacerbated that problem,” American Medical Association President Susan Bailey said.

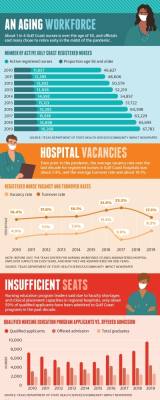

The median turnover rate for registered nurses in Gulf Coast hospitals was 17.5% in 2019, according to DSHS data. Since the pandemic began, many nurses have considered leaving the profession between the anxiety over bringing COVID-19 home to their families and losing at least 4,000 health care workers to the virus nationally, Bailey said.

On the other hand, health care workers have been promoted as heroes during the pandemic, and many have decided to enter the field as they learn more about the role, said Dr. Renae Schumann, the former dean of Houston Baptist University’s School of Nursing and Allied Health who now serves as District 9 president of the Texas Nurse Association.

“There’s the part of nursing where people are tired; they’re burned out; and they’re having a hard time staying in it. But there’s another part where people are looking at nursing and go, ‘I really want to be a part of that,’” Schumann said.

In the last decade, the Gulf Coast region’s supply of registered nurses has grown by 45%, according to the DSHS, but that growth is not enough to keep up with the population. Nursing education leaders said there is not necessarily a shortage of individuals interested in the profession, but admission to training programs is competitive and expensive.

Marinela Castano, director of the nursing program at Lone Star College-North Harris, said while the college’s nursing program had 600 applicants this past spring semester, LSC-North Harris is only able to accept a limited number of students to its programs.

The college accepts 30-50 students to its transition track—which is geared for students who are already licensed vocational nurses or paramedics—and 120 students to its basic track, which is geared for students with no prior health care experience. Castano said this capacity limit is in place because hospitals are only able to accept a few students for clinical placements.

“We are only allowed 10 students per faculty member when it comes to completing required clinical rotations, so we have to be thoughtful ... to ensure we can get students through all aspects of the program and into their nursing career in a timely manner,” she said. “We are continually seeking partnerships to expand the number of clinical sites at which our students can train.”

Long-standing shortage

While the pandemic amplified the state’s nursing shortage, experts said it has been a concern for years.

“I don’t believe we have ... at least in my career as a nurse in the last 25 years—that we’ve had an excess of nurses. We definitely have a shortage,” said Kelli Nations, chief nursing executive for HCA Houston Healthcare, which has a hospital in the Spring and Klein community.

“As our nursing workforce is aging and our population is aging, the nurses are retiring at a greater rate than we can hire, and our patient volume is increasing.”

About 24% of the region’s registered nursing workforce in 2019 was over the age of 55, according to the DSHS.

Nations said while Texas leaders have made efforts to increase the number of seats available in nursing schools, the rate of nurses graduating from those programs simply does not meet demand.

Additionally, Nations said nurses today can choose from a more diverse range of career pathways than ever before. HCA Houston Healthcare’s nursing senior team includes roles in clinical practice and operations, nursing clinical informatics, nursing analytics and care experience.

“We are quickly realizing that nurses play such an important role in the health care delivery model [and] that they have skills and talents that are beneficial for many roles that are not necessarily just at the bedside, so that bedside role is competing for a lot of other roles that need that nursing skillset and talent as well,” she said.

COVID-19, education complications

The pandemic has led to more nurses retiring early than hospitals would see in a typical year, according to Schumann. Others transitioned to travel nursing or part-time assignments to alleviate some of the stressors they faced, she said.

“When you are in a full-time position, most of the hospitals will have 12-hour shifts, which sounds great if you’re thinking, ‘Oh, well that means I get to work fewer days,’” she said. “Well, that’s true, but if you’re so tired that you’re sleeping through all your days off, then that’s not very helpful. COVID has been very difficult for nurses and health care workers in general.”

Despite this, many are still eager to enter the field of nursing, as applications to both medical and nursing schools are at an all-time high as the pandemic put a spotlight on these careers, Bailey said.

“One thing the pandemic has done, I think, is really shown that taking care of a patient in their most desperate hour is one of the most honorable things that a human being can do,” she said.

However, COVID-19 also interrupted nurse training programs at institutions such as LSC-North Harris. While faculty members continued instruction online last spring, lab hours could only be completed on campus, and capacity limitations in local hospitals grew stricter, Castano said.

To give students a head start, Spring, Klein and Cy-Fair ISDs each offer nursing pathways through their respective career and technical education programs at the secondary level.

In KISD, students who complete the district’s six-year advanced nursing pathway—which begins in ninth grade in partnership with Lone Star College-Tomball—can earn an associate of arts degree and an associate of applied sciences degree, while also becoming credentialed as a certified nursing assistant, a licensed vocational nurse and a registered nurse.

“Some of those kids are just barely 19 or 20 when they finish that program,” KISD CTE Director Deborah Bronner-Westerduin said. “And then students can continue on for a bachelor’s degree or go directly into the workforce, and many hospitals—if you’re an RN—they’ll pay for their employees to get their bachelor’s degree. So it’s a true win-win for our students.”

At the post-secondary level, the Spring and Klein community is also home to several workforce development programs including Springville Academy, Nursing Bridges Institute and Dotson Healthcare Institute, which offer CNA and phlebotomy courses as well as continuing education classes for health care workers.

Despite these offerings, however, faculty shortages and clinical placement capacities limit the number of new nurses produced e•very year. The DSHS reported 54% of qualified applicants were not granted admission to one of the region’s 27 prelicensure registered nurse education programs in 2019 due to a limited number of seats available.

The Texas Legislature created the Nursing Shortage Reduction Program in 2001, allowing the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board to provide dedicated funds to nursing education programs that increase the number of nursing graduates. According to the Texas Nurses Association, the number of new nurses produced grew by nearly 180% from 2002-19.

Schumann said faculty shortages remain an issue because earning the advanced degrees required is time consuming and expensive. The nursing faculty turnover rate in 2019 was 13%, and the vacancy rate was 6.5% for Gulf Coast-area programs.

“We absolutely need more faculty, which means that the schools have to pay the faculty something that they consider desirable enough to leave the hospital,” she said.