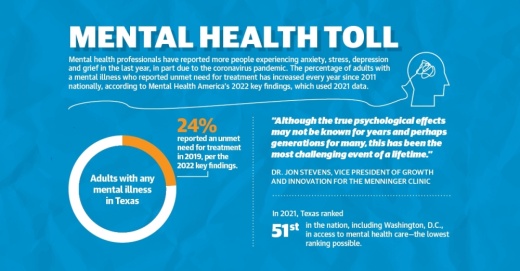

Mental Health America’s 2022 key findings, which use 2021 data, organized each state and Washington, D.C., based on mental illness prevalence and access to mental health care. Texas ranked 27th overall but was fourth in terms of prevalence of mental illness and 51st—the lowest possible—for access to care.

Local experts said access to mental health care has been an issue in Texas since long before the pandemic. In 2017, Mental Illness Policy Org. reported the state allocated 1.2% of its total state expenditures to mental illness; this compares with states on the higher end of spending, such as Arizona, Pennsylvania and Maine, which allocated 4.8%-5.6% of their expenditures to mental illness.

“Unfortunately, the mental health care system[s] in Houston and Texas proper were already inferior to many other states prior to the pandemic,” said Dr. Jon Stevens, vice president of growth and innovation for The Menninger Clinic, a Houston psychiatric facility. “Although the true psychological effects may not be known for years and perhaps generations for many, this has been the most challenging event of a lifetime.”

Mental health centers in Brazoria and Galveston counties said COVID-19 has exacerbated the anxiety and depression already present among residents as well as put even more strain on already understaffed clinics. Telehealth has improved access for some patients, and providers point to group support as a potential path forward for those hoping to improve their mental well-being.

Skyrocketing demand

Across the Pearland and Friendswood area, mental health providers and experts said the pandemic has underscored the need for more services as demand climbs.

In Galveston and Brazoria counties, the Gulf Coast Center serves as the local mental health, intellectual and developmental disability authority as well as a substance use recovery provider.

CEO Melissa Meadows said via email the center implemented a crisis counseling program designed for those in need of no-cost emotional support caused by the pandemic. From October 2020 to Jan. 25, 2022, the program served 908 individual participants and 2,041 group counseling participants, Gulf Coast Center officials said.

The center also gave mental health first aid courses to help participants learn to recognize when someone needs emotional support or mental health services, she said. Gulf Coast Center gave 29 trainings in Galveston County from fall 2019 to fall 2021.

Meanwhile, UTMB Health has two Webster locations that provide mental health services. While the patient volume has remained steady during the pandemic, clinics are limited based on the number of providers and their caps on caseloads, UTMB officials said.

UTMB Health Psychiatry Webster on Texas Avenue saw about 9,900 patients from September 2019 to August 2020; that number increased nearly 20% to about 11,800 patients seen from September 2020 to August 2021, according to UTMB data.

While the introduction of telehealth has opened doors in terms of access, the demand is greatly outpacing the number of providers available for counseling, said Jeff Temple, a professor and licensed psychologist at UTMB.

“There’s only so many hours and only so many people that an individual [provider] can see,” Temple said. “The increased access has helped, but the demand is so great that it still is leaving people lacking.”

COVID-19 stressors

The pandemic’s uncertainty combined with other major events, such as the February freeze, has created conditions that many are unable to cope with on their own, Temple said. He and Dwight Wolf, medical director for UTMB Health’s psychiatry and behavioral services outpatient clinic, said anxiety and depression among area patients have dramatically increased throughout COVID-19.

Burnout is a real possibility for providers as they try to tackle patients’ varying needs, whether remotely or in an office, Temple said.

“I could hire 10 psychologists, and they’d probably be full in a couple of months,” Temple said. “The demand is there. ... The providers just aren’t there.”

Many people wait until they are in crisis to seek help, resulting in a need for immediate intervention, and behavioral therapy is best provided in person, Meadows said. The increased stress and vulnerability people are feeling have led to higher incidents of crisis, she said.

According to Meadows and Galveston County Health District CEO Philip Keiser, the county has seen a rise in opiate-associated deaths and substance use during COVID-19.

Keiser emphasized substance use disorder clinics are needed now more than ever, and existing clinics can barely meet current needs. For those seeking mental health treatment, waitlists are long, Keiser added.

“If people have mental health issues, there are very few options for them if they don’t have money and insurance,” he said. “Quite frankly, there’s not a lot of options for people even if they do.”

Kristi Ottis, clinical therapist and CEO of Friendswood Counseling Center, said the waitlist at her center reached an all-time high in late 2021.

Ottis said she frequently must refer new patients requesting services to other centers when the Friendswood center’s caseloads are full. At least 100 new patients requested services in November and December who had to be referred elsewhere.

While Ottis also attributed the volume to holiday stressors, she said the waitlist shows an ongoing increase in need for mental health services.

“I’m definitely looking to hire additional clinicians ... because we have the need, and we really want to be able to meet the needs of the community,” she said.

Group support

Providers in Brazoria and Galveston counties said they hope community-centric interventions, from group therapy to support phone lines, can help residents make sustainable changes to their mental health moving forward.

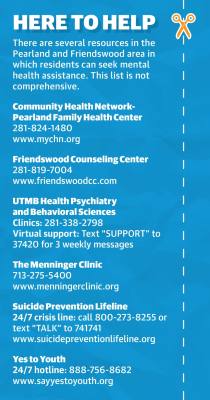

Community Health Network-Pearland Family Health Center offers primary care and behavioral health services, including individual and group counseling as well as psychiatry services.

In 2019, the CHN locations in Brazoria, Galveston and Harris counties provided behavioral health services to 16,585 patients. The patient load increased almost 53% between 2019 and 2020 to 25,375 patients, per CHN data. The demand for services increased again in 2021, with CHN providing behavioral health services to 35,843 individuals last year.

Additionally, CHN provided mental health services to more patients in the month of January than any other month; 3,400 patients were served—7.5% of which were in Pearland ZIP codes, said Ezreal Garcia, CHN director of community relations and emergency preparedness. He said he does not see it slowing down anytime soon.

“Just because an emergency situation dissipates or is eventually no longer in existence doesn’t mean that the trauma is [not] necessarily prevalent,” he said. “Some individuals may be more ... prepared or willing to come in to see counseling services because they can recognize those early onset challenges, [but] most individuals are not.”

He said this can happen for a variety of reasons, including the person may not have the time or capacity to evaluate their mental health or they may not be comfortable seeing a mental health specialist.

CHN offers individual and group counseling as well as psychiatry services in person and virtually. Although CHN offered telehealth prior to the pandemic, Garcia said virtual visits made up 85%-95% of patient visits in 2020. Now, virtual visits make up about 65%-70% of mental health-related visits, he said.

Meanwhile, UTMB has a text-based support service in which subscribers receive three weekly messages. Temple said these can be useful for substance use disorder tips and motivation.

For those hesitant to reach out for support, Ottis said help is available for those looking to reduce their symptoms and live a happier and healthier life.

“Asking for help is definitely not a sign of weakness; it’s actually a sign of strength, and it takes courage and vulnerability to reach out,” she said. “So I would encourage anyone who was having any type of struggle to not feel like, oh, it’s too big or this is too small to reach out for us for assistance or help with.”

Kelly Schafler contributed to this report.