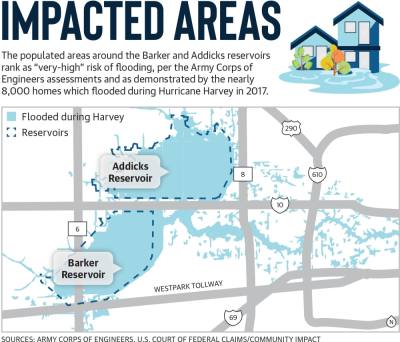

Harvey caused $125 billion in damages and flooded more than 25,000 homes in the Addicks, Barker and Buffalo Bayou watersheds, according to a post-Harvey analysis from the Harris County Flood Control District.

In one of several lawsuits following the storm, Presiding Judge Charles F. Lettow for the U.S. Court of Federal Claims awarded about $500,000 to homeowners in six test cases in an Oct. 28 ruling. Residents who saw similar damages have until Aug. 30 to file their own lawsuits for compensation.

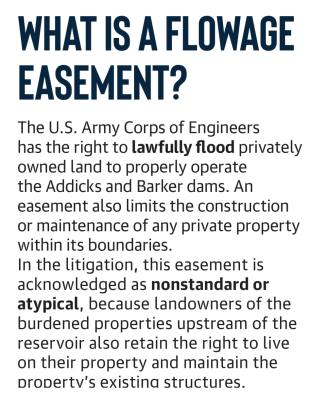

However, Lettow also ruled the Corps is afforded a “flowage easement,” which grants the agency permanent access to flood properties within the reservoirs up to the pool elevation met during Harvey, per the litigation docket.

Residents cannot sue if flooding occurs again, though the Corps’ policies for operating the dams remain unchanged, said Bear Creek Village resident Bill Cook, whose home sustained 12 inches of water in the storm.

“An easement that’s based upon reservoir elevation is very difficult for individual property owners to determine whether or not it covers them,” Cook said. “Most people do not know the elevation of their property, and so they may not even be aware that there’s a measurement or that it’s significant.”

The Corps appealed this decision in December, and a final ruling is not expected to come until 2024. The U.S. Department of Justice, which represents the Corps and other government entities in court, declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation.

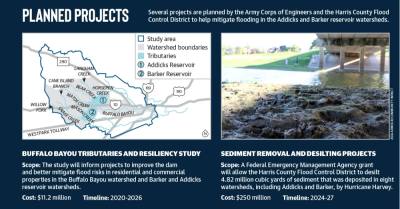

Meanwhile, the Corps and the HCFCD announced a new path forward for the Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Resiliency study Feb. 17. The $11.2 million study aims to find solutions that better mitigate flood risks to properties within Buffalo Bayou and the Addicks and Barker reservoirs.

Continued litigation

To protect downtown Houston during Hurricane Harvey, the Corps had to store water within the Barker and Addicks watersheds.

The Corps released water from the reservoirs to avoid an uncontrolled release over the dams, which caused homes both upstream and downstream to be inundated by the overflow, according to the HCFCD analysis.

A class action lawsuit, which was divided into homeowners upstream and downstream of the reservoirs, was filed against the Corps, Community Impact previously reported.

The October ruling determined the Corps may flood these areas. Local advocates and residents said they worry what protections they have if a similar event occurs.

Cook, who purchased his home in 1979, said he was told his neighborhood’s proximity to the reservoir at Hwy. 6 and Clay Road added to the marketability of his home.

“Because it would collect any flood water [and] rainwater, it had a park [and] recreational, open green space,” Cook said. “So it was presented to us as a benefit rather than a possible detriment.”

To Cook, the concept of a flowage easement is significant in determining future risks to property and people who live near the reservoirs.

“The people who are purchasing those homes have no familiarity at all with what any of this means or even if it’s going on,” he said.

Historical risks

The original intention of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs—which are owned by the federal government and operated by the Corps—was to reduce the risk of downstream flooding in the Houston area and the Houston Ship Channel, said David Mackintosh, chief of the Corps’ Houston Project Office. This mission has not changed, he said.

The reservoirs provide approximately 26,000 acres of flood storage to help reduce flooding downstream.

When the Addicks and Barker reservoirs were constructed in the 1940s, the area west of Houston was sparsely populated. However, the areas are now heavily urbanized with a population of 440,000 within its drainage area, according to initial analysis from the resiliency study.

Mike Dach, a homeowner with two rental properties on the perimeter of Barker Reservoir, has applied for compensation in the ongoing lawsuit. Each of his properties received 18-24 inches of water during Harvey.

If all eligible homeowners impacted by flooding apply for and receive the average award from the October judgement, the government could be liable for over $1 billion in damages. “When those dams were constructed, they were constructed out of dirt. Reinforced dirt, but just simply dirt,” Dach said.

Preliminary research for the Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Resiliency Study released in 2020 found that high water events and a need to release more water from the Addicks and Barker dams “pose unacceptable risks to life safety, private property and public infrastructure.”

Flood mitigation projects

The Corps and the HCFCD have implemented several projects in the Addicks and Barker reservoir watersheds, including the Corps’ $84 million project to replace the open outlet structures with adjacent gated dams.

The purpose of the dam project, which started in 2015 and finished in 2020, was to reduce the risk of dam failure, Mackintosh said. He confirmed the new gate’s intention is not to reduce flooding outcomes in a Harvey event.

“What they’ve done is they’ve taken a structure that was well past that service life that had been retrofitted, and it gave us ... [the ability] to build a stronger structure,” he said.

Additionally, the Federal Emergency Management Agency awarded the HCFCD $250 million in August 2021 to desilt 4.82 million cubic yards of sediment in eight watersheds, including Addicks and Barker, an HCFCD spokesperson said via email. HCFCD expects to hire a designer for the project this spring, and the first construction contracts will bid in early 2024. Construction could last 24-36 months.

The largest project, however, is the Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Resiliency Study, which the Corps began in 2020 to analyze the integrity of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs as well as the larger Buffalo Bayou watershed.

The HCFCD increased its participation in the study in February. The agency’s portion of the study will wrap up by December 2024, while the Corps will continue working on its portion of the study through 2026. The Corps plans to secure federal funding for the design and construction of any improvement project, per the study documents.

A system of underground tunnels from Barker Reservoir to the Galveston Bay is back in consideration. Previous estimates for the tunnel pegged the cost at around $2.6 billion, though the Corps’ study suggested it could cost as much as $12 billion.

Other alternatives for flood risk management listed in the interim report of the study include a third dam and reservoir at Cypress Creek.

The Barker Flood Prevention Advocacy Group released a statement of support Feb. 16, after the HCFCD announced its temporary leadership on the study, calling the agency’s move to provide funding “a significant one.”

“By partnering with the Galveston District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and expanding the scope [of drainage solutions] to include tunnels, the study will now continue instead of going the way of some past flood control studies which were closed and shelved with no tangible results,” the advocacy group said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has the right to lawfully flood privately owned land to properly operate the Addicks and Barker dams. An easement also limits the construction or maintenance of any private property within its boundaries. In the litigation, this easement is acknowledged as nonstandard or atypical, because landowners of the burdened properties upstream of the reservoir also retain the right to live on their property and maintain the property’s existing structures.