When he asked national experts which city to use as a model for mental health crisis response systems, Harris Center for Mental Health CEO Wayne Young said he was pointed back to Houston.

“They said, ‘If anyone else had made this call and asked where to look, we would have told them that Houston was the place to look in terms of innovation and collaboration,” said Young, a member of the mayor’s police reform task force who spoke to the City Council’s public safety committee in November.

In a separate report, the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration noted that Houston’s crisis intervention practices exceed national standards. It is one of 10 departments in the U.S. used to train other law enforcement agencies.

However, amid a national reckoning on policing and racial justice, Mayor Sylvester Turner’s Sept. 30 police reform task force report found, while Houston serves as a model and mental health initiatives are broadly supported, at least $13 million worth of added investment is needed.

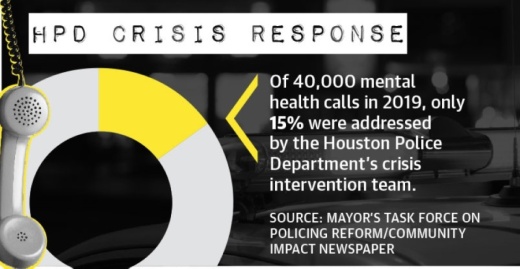

Of the 40,000 mental health-related calls made to the Houston Police Department in 2019, just 15% were addressed by the HPD Crisis Intervention Response Team, which deploys mental health professionals alongside police officers, department data shows. “The system is overburdened, and we have a shortage of mental health care providers,” said Renae Vania Tomczak, CEO of Mental Health America of Greater Houston. “There are ways to mitigate that, but as with everything, it comes down to the funding.”

Answering the call

For a city of over 600 square miles, the Houston Police Department has 12 Crisis Intervention Response Teams, but depending on staffing levels, the department may have only one team on duty during a given shift, HPD Assistant Chief Wendy Bainbridge told council members at the November committee meeting. The teams address situations during which a resident is experiencing a mental health crisis such as attempting suicide.

“The team could be responding to a call in Kingwood, and all of the sudden, they get dispatched to Southwest Houston,” she said.

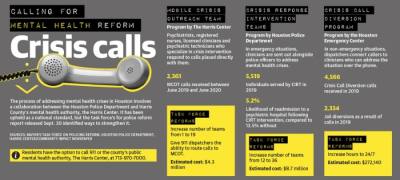

Another program, the Harris Center’s Mobile Crisis Outreach Team, attends to similar crises without the presence of law enforcement. However, the teams are not dispatched through the region’s 911 system and must be called directly.

The mayor’s task force recommended boosting funding for both programs and adding the mobile crisis outreach team to the 911 network to respond to calls that do not pose a public safety threat.

By making both programs more accessible, the task force said, the city can build upon its current successes.

Since 2014, only 4.1% of calls handled through HPD’s various mental health diversion initiatives have ended with the subject booked in the Harris County Jail, according to the task force report. The rest were diverted to psychiatric care or were resolved on-site, HPD data shows.

The likelihood of a resident being re-admitted into an area hospital for psychiatric evaluation declines after they interact with a crisis intervention team, the report found.

To fully staff both existing programs, the task force called for 24 new Crisis Intervention Response Teams, which would cost $8.7 million, and 18 more Mobile Crisis Outreach Teams, which would cost $4.3 million. It also calls for $272,140 in funding for the Crisis Call Diversion program, which connects 911 callers in less urgent situations with crisis counselors who can help them resolve issues over the phone. Additional funding would make the counselors available 24/7 rather than limit them to their existing schedule.

One program piloted within the Harris County Sheriff’s Office in 2019 put electronic tablets in the hands of officers to give them telehealth capabilities. A similar effort would cost HPD about $850,000, the report found.Despite these projected costs, staffing up also bears the potential for cost savings, the task force reported.

“It allows for that cost to be redirected to responding to something like a chest pain call or a significant public safety issue,” Young said.

In the meantime, a lack of capacity to respond to all mental health crisis related calls could have serious consequences, City Council Member Carolyn Evans Shabazz told fellow public safety committee members. In September, four Houston police officers were fired for shooting resident Nicolas Chavez 21 times while he was experiencing a mental health crisis.“I am concerned because a lot of times, I hear people say, ‘He just needed some mental help,’ and then, it escalates to someone getting shot and killed,” she said.

Pathways to funding

Funding the task force’s recommendations could simply be a matter of priorities, At-Large Council Member Sallie Alcorn said at the November public safety meeting.

“You have to look no further than the 2021 budget to see that this mental health division... is only $7 million out of a $944 million budget,” she said.However, as over 90% of the police budget is dedicated to personnel costs, there may be less leeway in the budget than some realize. Salaries and benefits are determined during contract negotiations between the Houston Police Officers Union and the mayor. The city’s contract is now under review.

Some see these negotiations and the annual budget process as opportunities to shift funds away from police and toward mental health programs housed in other departments, such as public health.

“Law enforcement wasn’t designed to manage people with mental health crises,” Vania Tomczak said. “We tend to think that people who have mental health issues are a danger, but that is not always the case. If we think about the flight or fight response, law enforcement has not been trained to think of the flight piece. They do what they can to mitigate the situation, but between their training and a physician’s training, it’s two totally different worlds.”

However, HPD may continue to play a key role in mental health response, said District C Council Member Abbie Kamin, who is also the chair of City Council’s Public Safety Committee.

“HPD does a really good job of getting federal grants. That’s part of why certain things fall under them. Just because something goes through the HPD budget doesn’t mean it doesn’t end up somewhere else,” Kamin said. “The mental health and crisis diversion money goes into HPD, but some of it goes to Harris Center for their programming.”

In some cases, current programs work because of relationships that have already been built, Bainbridge said.

“What is so vital to [the programs] is that the crisis teams will say, ‘This is their trigger word. Don’t say this.’ We work very well, and we know each other very well. ...this collaboration...[is] key to the great outcomes we see,” she said.