Formed amid calls for reform in 2011, Houston’s Police Oversight Board is facing new scrutiny in the aftermath of Houstonian George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody this spring.

The volunteer board serves as an independent check on Houston Police Department’s Internal Affairs Division, which investigates officer misconduct.

In recent years, criticism of the board has grown, even from some of its own members.

“There are a lot of great police officers, and I would’ve thought they would want to get rid of these guys that we see as repeat offenders,” board member Shelley Kennedy said. “You can see them, and it’s a sure pattern of their behavior when you read these complaints.”

The main concerns raised are that complaints are too difficult to file, that misconduct investigations by HPD’s Internal Affairs Division favor police and that too many members of the oversight board consistently approve Internal Affair’s assessments regardless of other members’ dissent.

Mayor Sylvester Turner’s task force on police reform dedicated a 15-page section of its Sept. 30 report to potential changes to the board.

Turner has publicly expressed interest in some of the recommendations, but changes are still being debated.

“With every single one of these recommendations, it requires resources, and there is a cost,” Houston City Council Member Abbie Kamin said; Kamin is also the chair of the city’s safety and homeland security committee.

At the same time, members of the Houston Police Officers Union have said the board is working as intended.

“[Activists] think that officers are just getting away with stuff all the time. It’s just not true,” HPOU Executive Director Ray Hunt said. “If they had ever been investigated by Internal Affairs, they wouldn’t believe that.”

Keeping track

Activists, task force members and former board members have all said the current misconduct review process makes filing complaints difficult and does little to factor in the number of complaints an officer receives over the course of their career.

Former board member Juan Antonio Sorto said that from the start of the process, filing complaints is not easy.

“I don’t even know how [complaints] work, and that’s a problem,” he said.

The board’s website lists local NAACP and League of United Latin American Citizens chapters and the Houston Office of Inspector General as collection points for complaints, but the mayor’s task force found those avenues have “fallen into disuse.”

Only allowing residents to submit complaints directly to HPD via phone or a notarized form creates a barrier, the task force concluded.

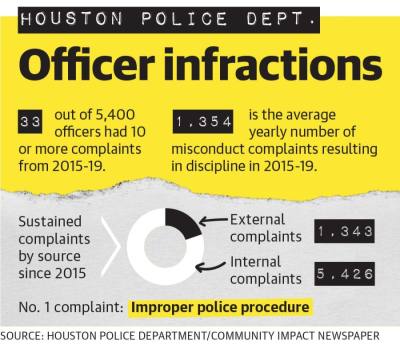

HPD data shows that between 2015 and 2019, 20 percent of complaints that ended with any type of sanction came from the public. The rest were filed internally among HPD personnel.

This lack of accessibility prompted local advocacy group Houston Justice to begin an effort to form its own online complaint system. Karla Brown, an organizer with the group, said the issue was highlighted by a botched no-knock raid in January 2019 that resulted in the deaths of an East End Houston couple, Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas. The aftermath of the raid, which was based on disputed evidence, saw several Houston police officers indicted—including Gerald Goines, who Brown said was known as a threat.

“What we’re seeing is that it takes somebody to die to bring attention to something that an officer had been doing for years,” she said.

The loss of community trust in misconduct reviews can have long-lasting effects, according to a November Kinder Institute of Urban Research report. It found Houston’s board the least effective oversight system among those in major Texas cities.

“Research suggests that the complete lack of an oversight agency is better for a city ... than if they have an agency that lacks effective legal and investigative powers,” it read.

Reviewing allegations

By the time a complaint makes it to the board, the task force and some board members argue, the HPD investigation of it favors police.

In August, nine-year board member Kristin Anderson wrote a resignation letter referring to the issue.

“[The Independent Police Oversight Board] operates inside a closed system without the ability to investigate, conduct its own interviews, or do anything else but follow the narrative offered to them,” she wrote.

Hunt, however, said he believes the process keeps out political influence.

“This is our careers on the line. So we want experienced investigators doing this and not some board created by a bunch of activists,” he said.

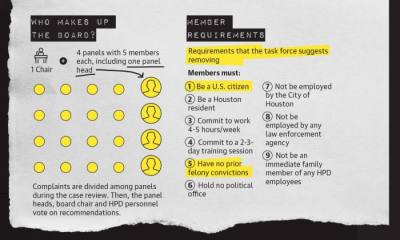

After complaints are reviewed by Internal Affairs, they are split among the board’s members, who are divided into four panels led by one panel head each. The members vote on whether to approve of Internal Affairs assessment.

All cases then return to HPD’s Administrative Disciplinary Committee, which is a combination of HPD staff and the board’s panel heads and chair. The disciplinary committee decides the officer’s punishment.

Kennedy said she has been troubled by the process because some panel heads and discipline committee members, she said, consistently vote in favor of Iax disciplinary measures regardless of the severity or frequency of complaints against an officer.

“No matter how much we scream and holler, we can still be outvoted,” she said.

This conflict came to head Sept. 10 when Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo fired four officers who shot and killed 27-year-old Nicolas Chavez while he was in a mental health crisis.

“It is distressing to the Task Force that the civilians put in place to hold officers accountable would defend these officers’ actions when even the Chief of Police himself said that he ‘cannot defend [the officers’] actions,’’ the task force report read, referencing Acevedo’s public remarks.

Hunt contended that the union and the police department do not have influence over the appointees, who are recommended by the mayor and approved by City Council.

“I really have great respect for our current Independent Police Oversight Board,” he said. “Sometimes, they agree with us. Sometimes, they don’t.”

When the panel heads do vote to overturn Internal Affairs’ assessments, Sorto said, he rarely gets confirmation that their opinion was considered.

“If we had any disagreements ... it was really hard to know what the outcomes were,” he said. “It still felt like we were just there to say there was a board representing the communities.”

What’s next

The task force report ultimately calls for a “hybrid” model of oversight borrowing from other cities’ accountability systems. It proposes forming an investigative unit paid by the city to serve alongside the board as well as reducing the number of two-year terms the board members can serve.

In the short-term, they suggest translating complaint forms into foreign languages and changing board membership requirements. Kamin said the investigative powers could come from strengthening the Office of Inspector General.

“One of my priorities is making sure that the Office of the Inspector General has the capacity to do those investigations as the public demands, and that is going to go hand in hand with [board] restructuring,” she said.

At the state level, Sen. Boris Miles, D-Houston, has filed legislation aiming to add subpoena power to the board’s investigative abilities.

Meanwhile, Brown said Houston Justice will continue working on its own database to track complaints. “It’s kind of like you’re asking the city to tell on themselves,” she said. “They tend to skew things in a more positive way.”