These anxieties were piled on top of the effects the pandemic has had on students outside of school, said Najmuddin, who taught Spanish at Rowe Middle School until February, when she left the position over her own concerns about the virus. About 85% of Rowe’s students are classified as economically disadvantaged, and 94% are students of color.

“Communities of color tend to have other issues that they have to deal with, whether that be poverty, food insecurity, job security [or] home insecurity,” Najmuddin said. “All of these other things that communities of color have historically been facing due to systemic racism is compounded in a pandemic. If you’re worried about where you’re getting your food from, you are not going to show up for Zoom [instruction].”

She said CFISD students and educators have faced challenges no one could have expected for a full year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and district data shows students are falling behind academically—especially those who were already at risk.

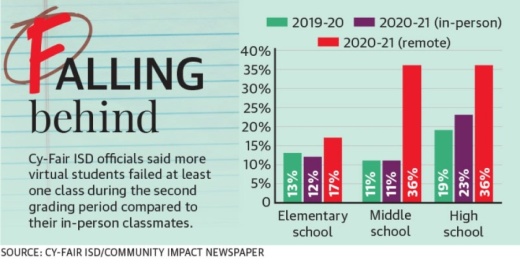

Chief Academic Officer Linda Macias told the board of trustees Feb. 8 she believes it would take two years to get students back to where they need to be academically due to the lost instruction time from this past year. District officials said they are also concerned about students who have participated in virtual learning all school year as they are lagging behind their peers taking their classes in person.

“These data are certainly indicating that the lost instructional time due to the COVID-19 pandemic has indeed created some significant learning gaps for our students,” she said. “I heard a presenter that called it not so much gaps as much as unfinished learning—they have not had the opportunity to have all the instruction, the learning that needs to be occurring.”

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, learning loss that began as early as March 2020 could affect students down the road. A study from global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimates an additional 232,000 high-school dropouts may be among the group of U.S. students who returned to in-person classrooms in September.

The district has implemented new initiatives and expanded the availability of existing programs to help close the learning gaps as quickly as possible. But officials said they rely on state funding to provide resources and sufficient staff members to execute them, and that stream of revenue could dwindle as attendance has dropped this school year.

Student performance

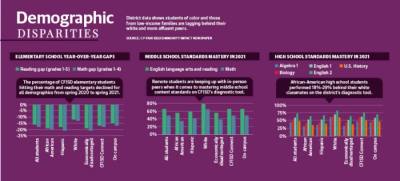

While the pandemic may have exacerbated the achievement gap among these demographics, it is not new. Students of color and English language learners, for example, are considered at risk due to a lack of equity in resources, said Robert Long, regional director for advocacy and research at statewide education nonprofit Raise Your Hand Texas.

“All those imprints become a barrier for students, and when they come to school ... we have to pour in more resources just in normal every day to make sure we can bring these kids to a point to where they can leave and really live [successful] lives on their own,” he said.

Fifty-five percent of CFISD’s enrollment is classified as economically disadvantaged, and most are students of color—45% are Hispanic and 19% are African American, according to the district.

The African American, economically disadvantaged and Hispanic populations appear to be struggling the most this school year based on district data. Officials said these subgroups have historically performed below their peers.

Najmuddin said she believes parent engagement is a key factor in the achievement gap, especially when parents are not native English speakers. While the district translates many of its messages in English and Spanish, there is a communication breakdown between teachers and parents on the day-to-day interactions about student performance, she said.

“If I were the parent of a child in Cy-Fair who didn’t know English, I would have to figure out Schoology in another language, how to email teachers in another language, how to figure out my child’s password. Things that are easy questions [for others] to just call the school and ask aren’t immediate things for those parents,” she said.

In addition to demographic disparities, Najmuddin said there is a gap between students learning remotely and those in the classroom setting.

While virtual students as a whole mastered the district’s content standards as often as or more often than those taking classes in person, data shows 36% of remote students were failing at least one course in the second grading period compared to 18% of on-campus students and 16% overall in 2019-20.

“It’s so hard trying to make sure that the students at home are getting the same quality of education as the students in person,” Najmuddin said.

She said the in-person students receive more attention than those learning online, but the expectations are the same for both groups. Additionally, the curriculum is often designed for on-campus instruction, and in-class activities that are not necessarily graded still feel like an assignment for students at home.

“We are all working around the clock. I receive messages from kids at 11 at night,” Najmuddin said. “Not only am I too exhausted to respond to that message, but now I know that 12-year-old kid who has to be in my class at 7 the next morning is also staying up all night doing work.”

Exploring solutions

Teachers are able to extend grace to struggling students, Najmuddin said, including giving 50s instead of 0s for missing assignments, being more flexible with late-work policies and creating make-up assignments—which can be difficult because teachers are already so stretched thin.

Macias said high school teachers are also offering multiple chances on assignments and assessments for seniors at risk of failing classes to keep them on track to graduate.

“Our teachers are doing a fantastic job, but there’s a lot of missed instructional time just because of the situation that we’re in,” Macias said. “They’ve got their groups going in their classroom, they have their groups going virtually, and it takes time to go from group to group to group.”

Several efforts are being made to help close learning gaps, including summer school availability for any student needing extra support; in-person and virtual tutoring opportunities; and additional resources in the Schoology platform.

Elementary reading levels have improved by 9% overall from fall 2020 to spring 2021, and Macias said 82%-87% of high school students are on track to pass their end-of-course exams this spring—compared to 78%-97% in 2019, according to the TEA.

Superintendent Mark Henry has expressed his concern of losing out on state funding due to lower attendance this school year if the state’s hold harmless policy was not extended into the spring semester. This provision, which state leaders announced in early March would be extended through the end of the school year, guarantees funding based on districts’ anticipated enrollment rather than their actual attendance numbers.

"As more districts return to in-person instruction, we are ensuring that schools are not financially penalized for declines in attendance due to COVID-19," Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said in a March 4 statement. "Providing a hold harmless for the remainder of the 2020-21 school year is a crucial part of our state's commitment to supporting our school systems and teachers and getting more students back in the classroom."

State Rep. Sam Harless, R-Spring, signed on to House Bill 1246 on Feb. 10, which would change the state’s funding formula for public schools to be based on student enrollment instead of attendance.

State Sen. Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston, who serves Cy-Fair and the Senate Education Committee, said he believes extending hold harmless through the first semester was the right decision but that the state must ultimately incentivize districts to locate students who have not been in school this year.

Bettencourt has been an advocate of reopening schools since the start of the school year and said he believes virtual learning is not the right long-term solution for most students.

“Eventually we’re going to have what I call a snapback problem because ... by August [I believe] we’re going to have a fully normalized school year,” he said. “That means there’s going to be a lot of catch-up learning that needs to be done.”