“I felt the need to be present in the protest in Houston because I believe the murder of George Floyd is a watershed moment in our country on the issue of injustice and police brutality,” he said. “I went there to let it be known that I’m a part of what I would call righteous indignation over what happened to George Floyd.”

As Floyd was handcuffed and lying face-down on the street, former Minneapolis PD Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds until he became unresponsive and was later pronounced dead at the hospital. Floyd was accused of using a counterfeit $20 bill at a market.

Alongside tens of thousands of others, Ogletree said he marched for justice and in the hope that those in positions of authority would recognize the rights endowed to all Americans in the Declaration of Independence: the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. He said his fellow protestors included individuals of all races and religious backgrounds unified in the same purpose.

“[Floyd’s] cry of ‘I can’t breathe’ is really a metaphor for every black, brown, Asian, Jew, every immigrant, every person in poverty ... basically, everybody’s saying ‘I want to breathe,’” Ogletree said. “I want to be able to get a job and not be looked at for the color of my skin. If I’ve been speeding or you suspect me of a crime, treat me like you would treat a white gentleman from River Oaks.”

Ogletree said while this rally was special for him to attend with his oldest son and three of his grandchildren, his experience protesting for justice began when he was a student at the University of Texas at Arlington. The school’s mascot from 1951-71 was the Rebels, and at every football game, the mascot would ride out on a horse waving a Confederate flag when the team scored a touchdown.

“Students got together and said, ‘We can’t take [this] anymore,’” he said. “We were in the stands, hoping our team never scored.”

Although this took place several decades ago, Ogletree said black Americans still deal with discrimination from their white neighbors who largely do not understand what African-Americans have experienced in the past or the present.

Most of the original signers of the Declaration of Independence were slave owners, and slavery was justified because many believed black Americans were not viewed as humans, Ogletree said.

“Even though they said, ‘All men are created equal,’ what they meant was ... all white men are created equal,” he said.

Because America’s foundation was set during this time of white men profiting off the free labor of African-Americans, Ogletree said white people should study this history to understand how America got to where it is today.

For instance, he said, following the Civil War, Southern states enacted Black Codes, which allowed white citizens to charge innocent black people with crimes and force them to work for low wages. Thousands of lynchings took place between the eras of the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, which legalized segregation in the South, he said.

“There are whites that say, ‘Well, gosh, I didn’t do that, so why do you want to hold it against me?’” Ogletree said. “But the bottom line is you benefited from it. It’s not your fault, but you benefited from it, and it still [is] a problem in America.”

For those looking to understand more about racism in America, Ogletree recommended the books “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander and “Just Mercy” by Bryan Stevenson as well as an article titled “The Double Standard of the American Riot” published by Kellie Carter Jackson in The Atlantic.

Prejudice persists

The Cy-Fair community is not immune to racial profiling, Ogletree said. In fact, he said he still periodically reminds his three sons, all of whom are CFISD graduates and are married with children of their own now, to drive carefully and always follow speed limits.

One of his church members who lives in the Fairfield community recently shared with Ogletree that his teenage son was pulled over by law enforcement in his own neighborhood, asked to get out of the vehicle, questioned about where he was going and frisked. The officer did not bother to question the son’s two white friends, who were in the car with him, he said.

“It was this real, scary moment where ... there are three guys in a car, and you’re only messing with one. And of course, none of them had done anything,” he said. “There is story after story like that, but it’s something that you always are conscious of."

Ogletree recalls seeing reports of racial discrimination in a Houston-area Dillard’s department store years ago.

“I’ll never forget, I had to go into Dillard’s a short time after that, and I was so conscious of that that I stayed in the big center aisles as I walked through there trying to make sure I didn’t do anything that looked suspicious,” he said. “That’s just stuff you go through.”

Faith and justice

Ogletree founded First Metropolitan Church in 1986 and serves as senior pastor at the church, which is located off Beltway 8 near West Road.

He said he preaches that Christians should love their neighbor as they love themselves, as Jesus taught in the New Testament, which spends a lot of time on the topic of forgiveness.

The Old Testament repeatedly covers the concept of justice, which Ogletree said is defined in the Bible as righting a wrong.

“I believe in love and forgiveness, in being neighborly,” he said. “But I do believe in taking a stand, trying to address a wrong and fighting for justice. ... In the Old Testament, the word 'justice' is used over 200 times. That’s how important it is to God.”

Striving for diversity

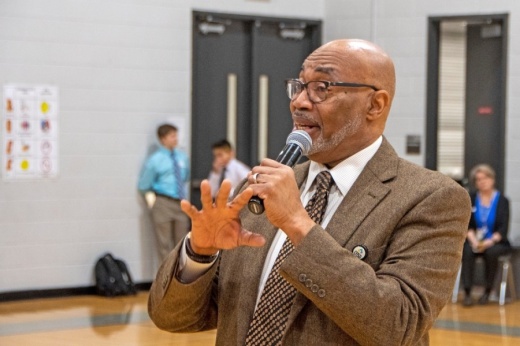

As the only black member of CFISD’s board of trustees, Ogletree said it is important that those in authority can bring different perspectives to their work.

“Diversity is so important because it helps to always have someone at the table whose experiences are different than yours, whose perception is different and who can add something ... you hadn’t even thought of,” he said.

CFISD promotes “opportunity for all” in the district, and Ogletree said officials are striving to increase representation to better serve its students.

In a district with more than 100 ethnicities represented among its student population, Ogletree said embracing diversity is necessary.

“What would it say to them if all they saw on our school board were white men?” he said. “They need to see diversity. It helps them to see a model.”