When Irving campaigned for a seat on the CFISD school board in November—which was ultimately won by Gilbert Sarabia—the Langham Creek High School alumnus and University of Houston student said one of his top priorities was equal representation in an increasingly diverse school district.

“When you have a majority-minority school district like we’re becoming ... especially from a student perspective, it’s important to have educators that look like you or that can relate to you or that may understand the different backgrounds that you come from,” Irving said.

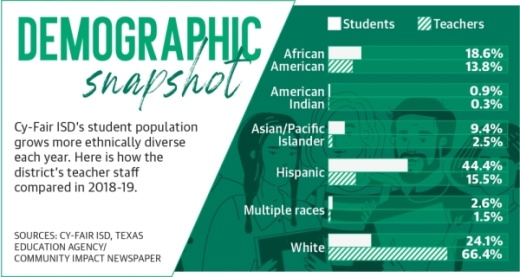

While the district’s student population speaks more than 100 languages and dialects and is only 24% white, the majority of educators are white.

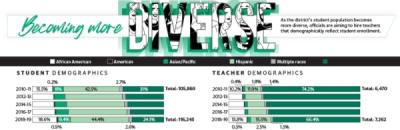

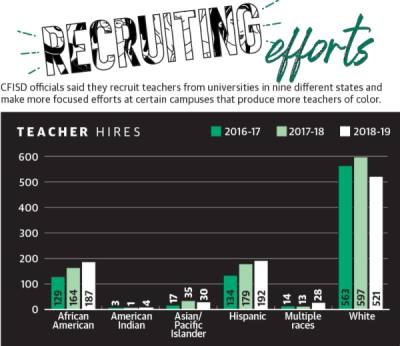

Last year, 66% of teachers in CFISD were white, according to state data. CFISD officials have managed to hire more teachers of color in recent years—from 297 teachers in 2016-17 to 441 in 2018-19—and said their goal is to recruit diverse educators who reflect student demographics.

Statewide, teachers are 11% black, 28% Hispanic and 58% white. Students across the state are 13% black, 53% Hispanic and 27% white, according to the Texas Education Agency.

“Providing diverse environments prepares our students for the diverse global roles they will have as leaders,” said Deborah Stewart, the chief of employee and student services.

Black and Hispanic students in CFISD are passing standardized tests and graduating on time less frequently than their white counterparts, although officials said they believe this achievement gap may correlate with poverty rates more than demographics.

Diverse teacher representation can positively affect student outcomes and better set them up for future success, according to Laura Owen, who serves as the director of the Center for Postsecondary Readiness and Success as well as a research associate professor at American University.

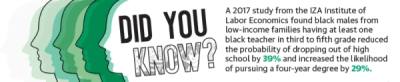

A 2017 study from the IZA Institute of Labor Economics found black males from low-income families who had at least one black teacher in third to fifth grade were 39% less likely to drop out of high school and 29% more likely to pursue a four-year degree.

“We know that if our minority students have at least one same-race teacher ... they do better on standardized tests; they have better attendance; they’re suspended less frequently,” Owen said. “If we do not have teachers of color who are on our staff who are working with our students, then we miss opportunities to question assumptions that we make about race and privilege.”

Changing demographics

In the last 10 years, CFISD’s student enrollment has gone from 36% white students in 2009-10 to 24% in 2018-19, and minority populations have increased every year since.

“I remember when I was in first grade, I was the only African-American male in my class,” Irving said. “Probably when I got to middle school, I started to notice a whole lot more diversity—not just with African Americans and Hispanics, but [also] with different people from the Middle Eastern communities.”

A 2019 report from demographics firm Population and Survey Analysts found CFISD saw 1,200 new immigrant students in 2018-19 and stated the trend is likely to continue.

Owen said racially disproportionate student-to-teacher ratios in Texas can be traced back to the U.S. Supreme Court deeming racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional in 1954.

Following the integration of public schools, many black teachers who formerly worked at black schools were pushed out of the system, said Wes Pratt, chief diversity officer at Missouri State University.

“Such teachers [were] inspirational, educational, supportive and nurturing for students denied access and were not permitted to integrate into a public school infrastructure that was legally required to educate their children,” he said.

By the time the U.S. Department of Justice mandated desegregation, 800 students attended Carverdale School, which served black students from 1925-67 in Cy-Fair. The district now enrolls nearly 22,000 black students.

CFISD officials said they have initiatives in place to meet its diverse population’s needs, including New Arrival Centers to support students who are new to the country, a team of youth service specialists who support and direct resources to at-risk students and their families, and the College Academy, which allows economically disadvantaged students to earn an associate degree through the Lone Star College System at minimal cost.

“The demographics of Cypress-Fairbanks ISD mirror those of the state, and we welcome the opportunities that a diverse student population provides,” Chief Academic Officer Linda Macias said.

Diversifying hires

Andrea Chevalier grew up learning about the different cultures of her diverse peers in Spring Branch ISD and went on to teach for four years in Dallas and Leander before moving into her role as a lobbyist with the Association of Texas Professional Educators based in Austin.

Having grown up in a diverse community, Chevalier said she thought she was prepared to cater to children from different backgrounds, but when she became a teacher she began to recognize implicit biases.

“A challenge is more so for the adults to remember that the world that we grew up in is not the world that exists now, and so they need to still be willing to change the way that they think,” she said. “Changing adult behavior is pretty hard. It takes a lot of ... professional development and a lot of uncomfortable situations, especially when you’re talking about race.”

CFISD’s 2019-20 board monitoring system—an annual report that measures the district’s progress on various objectives—lays out a goal to “recruit, develop and retain highly qualified and effective personnel reflective of student demographics.”

Chairita Franklin, the district’s assistant superintendent for human resources, said of the 25,000 teacher applications CFISD received in 2018-19, 962 were hired—54% of which were white. Just two years earlier in 2016-17, 66% of teacher hires were white, according to the district.

“Our district’s goal is to focus on recruiting a diverse leadership staff ... which includes executives, principals and teachers,” Franklin said at a November board work session.

According to Franklin, focused efforts are made in CFISD to recruit ethnically and racially diverse teachers from schools including the University of Houston, Texas Southern University, Houston Baptist University and Prairie View A&M University.

“Partnerships with universities and alternative certification programs have proven to be beneficial in our efforts to recruit diverse educators,” she said.

The district also tries to provide competitive salaries for all employees, according to the board monitoring system. In June, the district increased the starting teacher salary from $54,000 to $55,500. All teachers have access to professional development and internal promotion opportunities as well, Stewart said.

Natasha Truitt, executive director of human resources for the Harris County Department of Education, said the organization recruits from the communities it serves—which includes CFISD and 24 other school districts—to ensure its workforce is equally diverse.

Truitt said employees, students and parents alike appreciate when a district’s educators reflect their cultural and racial backgrounds.

“With a diverse teaching staff, students benefit from a variety of perspectives, experiences and talents,” she said. “In addition, a diverse staff often allows parents and students to have confidence that the organization and staff can readily identify needs of students and provide programs and services to ensure student success.”

Addressing poverty

When Irving reached third grade, he had his first black teacher in CFISD. He said this was especially meaningful for him while he was being raised by a single mother.

“I had someone who’s kind of like a father figure—someone that’s understanding the background of my community and culture,” he said. “As [someone who] was almost homeless twice during my sophomore year during oil and gas layoffs, it would have been extremely helpful if I had somebody ... that would have understood the different things that happen to minorities in different communities.”

Owen said there is progress to be made toward diversifying the teacher pool in Texas schools, but many districts across the state have embraced this goal because of the research that shows students benefit socially, emotionally and academically.

While black and Hispanic students are passing standardized tests 9%-21% less often than their white peers, districts officials said they believe a student’s economic status is a more significant factor than his or her race and ethnicity. Economically disadvantaged students passed standardized tests 5%-9% less often than the total student population in 2018-19, according to CFISD.

Even so, the district’s overall student population outperformed the state’s overall student population in every subject tested by 4%-9%.

“Our goal is to eliminate the achievement gap by providing meaningful educational experiences to economically disadvantaged students,” Macias said.

Chevalier said the correlation between test scores and poverty is one seen across the state, but there is typically a similar correlation between poverty and demographics.

The Texas school finance system has certain formula weights that provide additional revenue for low-income students and English language learners, Chevalier said, and she believes increasing those weights is important.

“It’s not that those students are less capable of learning,” she said. “There are other things happening around them, other struggles in their lives—maybe there’s food insecurity, housing insecurity—things that are causing them to struggle academically.”