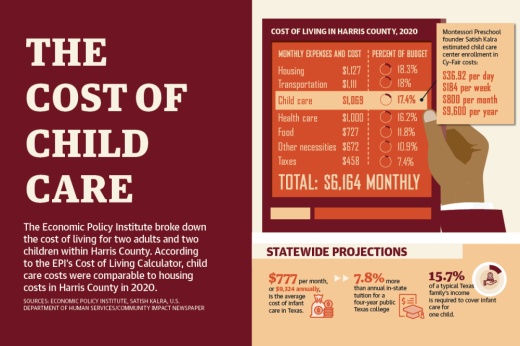

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, child care is considered unaffordable if it requires over 7% of a family’s income. As of October 2020, the typical Texas family was paying 15.7% of its income for infant care for one child, according to the Economic Policy Institute. By this standard, 15.8% of families could afford infant care.

While child care is an important service for working parents, it can be costly due to state staffing requirements, local child care officials said.

At The Honey Tree Preschool, a child care center serving Cy-Fair for 40 years, owner Helen Fox said she exceeds required staffing numbers to avoid burnout among employees. She said she has not raised prices in almost six years but is now having to balance the cost of paying her employees fairly and not pricing out the parents who rely on her.

“So the main concern for us is keeping these children healthy, happy and safe,” Fox said. “We just are seriously considering what we’re going to do price wise right now because you don’t want to price yourself to a point where the parents can’t afford to bring their children here or even have day care.”

On June 14, the Harris County Commissioners Court approved the use of $48 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds for a new child care and early childhood development program that aims to increase the accessibility of child care in Harris County by 10%.

According to a June 13 news release, the program will be a three-year pilot to create more child care options for children age 3 and younger in Harris County communities. Funds will also be allocated to provide child care workers with better wages and to help child care centers recover from pandemic-induced hardships. County officials said once a request for proposal is awarded, the program will come back to commissioners for approval.

“Early childhood programs have one of the strongest returns on investment of any type of public program,” Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo said in a statement. “Those positive effects also endure throughout the child’s life.”

Increasing costs

As of October 2020, the average cost of infant care in Texas was $777 per month, or $9,324 annually—7.8% more expensive than the annual in-state tuition for a four-year public college in Texas, according to the EPI.

Comparatively, Brightwheel, a child care management software company, reported June 8 the average price of child care in the Houston region as $1,087 monthly. The group reported an 8% average increase in prices for child care between 2021 and 2022. However, Brightwheel reported Cy-Fair ZIP code 77064 as one of the most affordable in the metropolitan area with an average monthly cost of $495.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index—a measure of the average change in prices—the cost for day care and preschool rose 3.2% nationally from May 2021 to May 2022.

Fox said she is proud of not raising her prices in almost six years but is now having to look at incrementally raising prices to provide her staff with adequate pay.

“If every room was at capacity where we’re supposed to be we would be fine,” Fox said. “But right now because we’re not at capacity, but I then have to consider salaries. I have staff that haven’t had raises in a while and they need them, so that’s what I’m slowly doing is boosting [rates] because I want to take care of the staff.”

While parents are spending more on child care than they were two years ago, child care centers are also facing higher costs and other industry issues related to the economic downturn.

Satish Kalra, founder of Montessori Preschool, which has three locations in Cy-Fair, said while some supply costs have gone up, his business has been hit harder by other costs.

“The biggest cost in the center besides all others is the real estate cost and the staff costs,” he said.

As for real estate costs, Satish Kalra said child care centers are required to have a minimum of 30 square feet per child. This means a facility aiming to hold 100 children would require at least 3,000 square feet—excluding office space, entryways and playgrounds—making renting or owning a facility costly in the current real estate market.

About 21% of child care centers in Texas had closed due to financial hardships induced by the pandemic as of September 2021, said Kim Kofron, the director of early childhood education with Texas-based nonprofit Children at Risk. Kofron said these closures further exacerbated child care deserts, or ZIP codes with fewer than 36 child care seats per 100 children of working parents.

According to data from the Center for American Progress, there is an adequate supply of child care centers in the southeast portion of Cy-Fair. However, the more recently developed neighborhoods in northwest Cy-Fair do not yet have sufficient centers to meet the needs of families.

Kevin Kalra, director of innovation and global strategy for Montessori Preschool, said he believes the number of early education centers in Cy-Fair is not enough to meet the needs of the community’s growing population. According to a 2021-22 report from demographics firm Population and Survey Analysts, local families have about 56 private preschool options.

“If you look and calculate the total number of seats that are actually available, ... we don’t have enough seats to meet the overall demand,” Kevin Kalra said.

Staffing challenges

Satish Kalra said staffing cost increases are being felt as Texas requires certain teacher-to-student ratios for child care centers. While having more teachers helps with managing classrooms and ensuring facilities are able to host full classes when a teacher is out sick, new employees are hard to come by.

“So because of the pandemic, you can say whether it was strictly because of the pandemic or other policies that came into force, the staff availability has gone down, and staff costs have gone up,” he said.

A survey released in February by the National Association for the Education of Young Children reported two-thirds of child care centers in the U.S. are experiencing a staffing shortage. A September 2021 NAEYC survey reported 86% of child care centers in Texas saw staffing shortages; 79% of those surveyed identified wages as the main recruitment challenge.

In May 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the average annual wage for a child care worker in the Greater Houston area was $24,150—the ninth lowest-paying occupation out of the 709 occupations in the region that receive an annual wage.

Officials with Montessori Preschool and The Honey Tree Preschool said they have retained staff members for years but have had to find more teachers to fill in when one is unable to work. This has proven a challenge for both centers as they maintain high standards to ensure parents are pleased with the care they provide.

Resources and funding

With the 88th Texas Legislature set to begin Jan. 10, many parents are looking to local legislators for assistance. In a June 23 email, state Rep. Sam Harless, R-Spring, said child care costs are “eating up a larger portion of income” for families with children.

“We are hearing more requests and higher demand for increased state funding in a number of areas. ... In the end, it will likely come down to available budget dollars,” Harless said.

Parents whose children meet certain eligibility criteria can take advantage of Cy-Fair ISD’s free pre-K program, which serves those who are age 4 on or before Sept. 1. The child must be unable to speak or comprehend English, be economically disadvantaged, be homeless, be a child of an active duty service member or have been in foster care.

Many local child care centers offer financial aid to ease the burden for low-income families. The Honey Tree Preschool partners with Workforce Solutions, a group that helps employers meet their human resource needs and aids individuals in career development, to help student and working parents pay for child care.

“In other words, I agree to accept less than what my normal tuition is, and the Workforce [Solutions] pays me a certain amount,” Fox said. “And plus, whatever the parent fees; some parents have zero fees.”

Kofron said she hopes to see state and federal legislators continue to invest in child care in the future.

“We really want to make sure that as we plan into next year as when those funds run out that there’s some mechanisms in place to make sure that the bottom doesn’t fall out,” Kofron said.

Ally Bolender contributed to this report.