“This pandemic is different ... from anything anyone has ever seen,” said Jennifer Landers, the executive director of Community Assistance Center, a Conroe-based essential assistance organization. “We have a lot of folks that have never needed assistance before that are having to come out for financial assistance [and] for food assistance.”

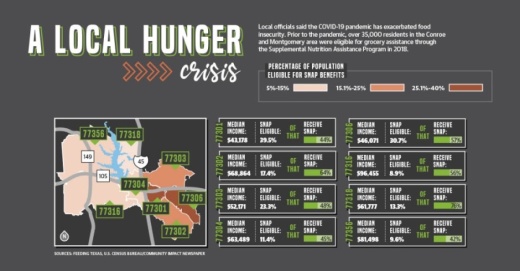

Even before the onset of the pandemic this spring, about 12.5% of Montgomery County’s population struggled with food insecurity—a term defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.

Higher unemployment rates this year have since driven an increase in food insecurity, and the area has seen a greater need for food, said Kristine Marlow, the president and CEO of the Montgomery County Food Bank.

The Texas Workforce Commission reported a total of 60,347 unemployment claims from Montgomery County residents from early March to mid-October, up from 7,138 claims during the same time last year—which is a 745.43% increase year over year.

“When the pandemic began ... in March, a lot of people lost their jobs or found themselves in a place where they couldn’t pay their bills or were not able to afford food,” Marlow said. “So, the food bank ... increased their giving and the way that they were distributing food.”

Financial strains

Celia Cole, the CEO of hunger relief organization Feeding Texas, said food insecurity is directly related to economic insecurity.“For some, that means an intermittent bout of hunger toward the end of the month when funds are low,” Cole said. “For others, it’s a constant state of hunger and reduced access to food.”

At the height of the pandemic from April to June, Landers said the nonprofit saw a 1,043% increase in the amount of food being served to individuals.

Landers said many of these new faces are households that fall under the ALICE threshold—households that are asset limited, income constrained and employed, according to research by United For ALICE, a national financial hardship research project. For these households, families often earn more than the federal poverty level, but it is still not enough to cover the basic cost of living.

While 14% and 13% of households in the census-designated places of Willis and Conroe, respectively, lived under the federal poverty level in 2019, almost 47% and 41%, respectively, lived below the ALICE threshold. In Montgomery, 27% of households lived under the ALICE threshold, while 18% lived below the poverty line.

“[For] some of these folks that are ... middle class or upper middle class—just because they’re making great money and doing well doesn’t mean they’re not living paycheck to paycheck,” Landers said.

Effects of food insecurity••Local organizations and food pantries try to provide nutritious food to those in need, as food insecurity often leads to a poor diet, which can cause heart disease, obesity and other health conditions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Marlow said over 44% of food given out by the Montgomery County Food Bank, located in Conroe, is nutritious items such as fresh produce, dairy and meat.

Residents in Texas spend the second most per capita on health care costs associated with food insecurity among all states, according to a 2019 study from Preventing Chronic Disease, a journal sponsored by the CDC.

“If you’re worried about where your next meal is coming from ... or how you’re going to keep a roof over everyone else’s head, you can’t even begin to think about stabilizing,” Landers said. “A lot of the folks we’re seeing are just in survival mode.”

School districts and local organizations have also worked to supply food to children during this time. Montgomery ISD distributed 15,388 free curbside meals from March to May for students as campuses were closed this spring and summer. Willis ISD provided 297,954 free meals from April to October, according to the district. Conroe ISD also provided meals but did not provide the number distributed before press time.

According to Feeding America, 12.5% of Montgomery County’s overall population and 18.5% of its children were considered food insecure in 2018. Due in part to the pandemic, those numbers in 2020 are projected to be 16.1% and 25.5%, respectively, as of press time.

School districts are partnering with the USDA to continue offering on-campus and curbside meals free to all students regardless of financial need throughout the 2020-21 school year, the USDA announced in an Oct. 9 press release.

“As our nation recovers and reopens, we want to ensure that children continue to receive the nutritious breakfasts and lunches they count on during the school year wherever they are, and however they are learning,” U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said in the release.

Nonprofits step up

Federal programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program can help offset the cost of groceries for low-income families. But according to Feeding Texas, the program covers only about $1.26 of the $2.80 it costs to purchase a nutritious meal at the average Montgomery County grocery store. Community organizations can help families fill the gap. ••Kids’ Meals is one such nonprofit ramping up to meet an increased demand for food services in Montgomery County, specifically against childhood hunger. With 14 years of service in Harris County, the organization expanded its services into Montgomery County in 2019 to provide food for families with children who are too young to attend school.Laran Cone, the Montgomery County expansion route director for Kids’ Meals, said the program typically serves preschoolers who are not enrolled in school yet to receive free meals.

“With all the kids home and extra families coming on the program because ... they’re out of work [or] they don’t have the funds to provide, ... we’re just trying to keep them from being homeless,” Cone said. “Basically, we’re trying to help them feed their kids so they don’t have to wonder if they have to feed the kids or pay their electric bill or pay the rent.”

Landers said the Community Assistance Center in Montgomery County has seen a 600% increase in food assistance and 200% increase in financial assistance needs compared to last year. At the pandemic’s onset in late March, Landers said an estimated 500 families came to collect food donations at the organization’s weekly Saturday market, which usually serves fewer than 300.

According to Landers, an influx of community support through volunteers and donations has helped the organizations meet increased demand.

“Our community is incredibly giving and incredibly resilient,” Landers said. “We have had so many new volunteers come out and join us and start helping; so many new donors come out and step up and make sure that we have what we need.”

The Montgomery County Food Bank has also seen a greater demand for food donations, as the organization has offered over 150 mobile markets since the pandemic began this spring compared to 33 markets total last year. Marlow said the food bank has served 6.9 million meals to an estimated 462,000 individuals since March.

With the holiday season around the corner, Marlow said more resources and volunteers will be needed to keep up the help and continue meeting needs.

“[In] seeing businesses that still have not opened up yet, still seeing the schools that are struggling to be at max capacity, ... there are still ... thousands of people being laid off. We’re prepared to keep up this pace for just, you know, as long as we need to,” Marlow said.

Additional reporting by Danica Lloyd