First it was a messaging campaign to let people know how to prepare for what ended up being a historic storm for Texas. League City prepared by purchasing salt, making sure vehicles worked and readying road barricades for potential closures.

At this point, the city did not know what it was in for, City Manager John Baumgartner said.

The second wave was keeping people warm and buildings operational during nearly 72 hours of power outages. The city opened park buildings, City Hall and other facilities for residents to charge their phones and warm up. All but 15 traffic signals across the city lost power, and city workers had to use portable generators to keep wastewater, Public Works Director Jodi Hooks said.

“Folks were working 20-hour days easy,” Baumgartner said.

Yet another wave was responding to endless calls for burst pipes. City staff had to be ready 24/7 to go to residents’ homes to shut off water mains to prevent broken pipes from continuing to flood homes, Baumgartner said.

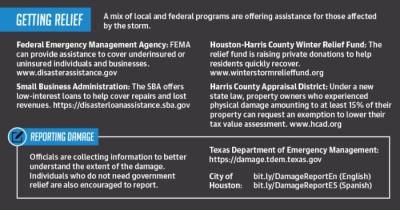

Now, over a month later, residents most affected are still reeling and trying to restore their lives after a storm that was just as destructive to some as Hurricane Harvey. Meanwhile, policymakers are trying to make sure something like this does not happen again.

Devastation

Bobby Jo “BJ” Stampley, owner of Maverick Remodeling and Construction in Clear Lake, began working around Feb. 10.

He did not take a day off until March 13.

For over a month, Stampley and his disaster response crew worked tirelessly to help Bay Area residents recover from the storm. Stampley, who was around for Harvey and other hurricanes, said this storm was just as horrible for those affected.

“This is the biggest cluster I have ever seen in my entire life,” he said.

Thousands across the area had burst pipes that damaged their homes. The pipes broke due to water freezing from a lack of heat after power outages. Some breaks were so bad that homes’ interiors were completely destroyed, causing tens of thousands of dollars worth of damage, Stampley said.

One large home on Garden Drive in Friendswood has been almost completely gutted, Stampley said. The pipes burst while the family was vacationing, and the family returned to a flooded home.

Similar destruction occurred at a house on Cameo Court in League City and another on Throndon Park Court in Clear Lake. The homes have to have their walls ripped out, their floors and ceilings replaced, and potentially new piping put in before their owners can move back in, Stampley said.

The damage was so great because many were not aware their homes were flooding; they were staying with friends or family who had power and returned to a flooded house.

“It’s sickening,” Stampley said of the realization that your home has been destroyed. “It’s absolutely sickening.”

Stampley and his crews are in the process of drying out many of these houses, a process that takes days. With temperatures rising, the risk of mold growing is increasing, Stampley said.

After, the interiors that cannot be salvaged are demolished, and then Stampley’s business helps remodel the homes. In the meantime, it is difficult to witness the devastation the storm has caused for so many, he said.

“I don’t know what to do,” Stampley said.

Learning from experience

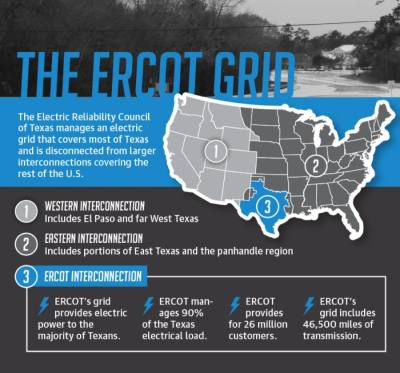

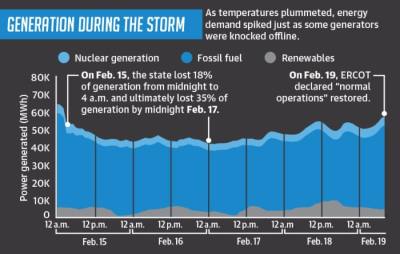

The morning of Feb. 15, the winter storm knocked power plants out across the state, at its peak affecting 4 million customers. What began as planned rolling blackouts to conserve power became up to 72 hours of no power for some, which is what led to burst pipes, officials said.

The state narrowly avoided a statewide blackout, which would have taken weeks to fix, said Bill Magness, the former CEO of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas.

“If we have a blackout of the system, the system is out for an indeterminate amount of time,” Magness said in a Feb. 24 emergency meeting. “We may still be here today talking about when is the power going to come back on.”

Magness said the crisis was a result of the storm and the state’s power generators’ inability to work in such extreme weather, as there are no regulations requiring power plants to reinforce themselves against the weather.

League City officials said they learned a lot from the storm.

For instance, one responsibility the city had was using 100-gallon tanks to transport diesel fuel from gas stations and other sources to generators across the city.

“That was a full 24-hour task,” Hooks said.

At one point, the city borrowed about 3,000 gallons of diesel from Clear Creek ISD to keep generators operational. The city is considering getting bigger tanks to transport more at once and having more diesel readily available to begin with, Hooks and Baumgartner said.

With cell service out, city staff had to rely on radios to communicate, which was another lesson, Baumgartner said.

Baumgartner commended the public works staff for their tireless work throughout the weeklong storm.

“They were the champions of the event,” he said.

Community comes together

Despite the destruction, residents have reported seeing people helping each other throughout the storm and its aftermath.

“Neighbors are helping neighbors, especially the elderly,” Stampley said.

One of Stampley’s customers is an elderly Vietnam veteran. When her home was destroyed from a burst pipe, an “army” of people showed up to help her pack her things and move them to the garage to dry or to her new temporary residence, Stampley said.

Mike Lopez, owner of TGS Home Services, a home repair business, said younger neighbors checked on him during the storm, and he took the time to check on single women in the area. Since the storm receded, he has seen neighbors help each other pull out wet insulation and carpet in damaged homes, Lopez said.

Eileen Halm, who lives in Pipers Meadows, lost power for nearly three full days. Being prepared for a hurricane meant she was prepared for the winter storm. She, too, saw people helping each other during the cold weather, including residents across the street who shared a generator with their neighbors so they could at least keep their lights on, she said.

“We have a lot of neighbors that look out for neighbors,” Halm said of her subdivision.

When it came to League City workers, the community stepped up to keep them fed. Esteban’s provided free food to hundreds of city staff during the storm, as did other local restaurants. Clear Creek ISD opened a cafeteria and fed League City police, fire and medical workers, Baumgartner said.

Additionally, cities are trying to be compassionate to those who experienced leaks. Both Houston and League City approved temporarily lowering water rates throughout the storm so those who ran their faucets to prevent frozen pipes and those who had burst pipes will see smaller water bills.

Making changes

Several ERCOT board members resigned in the aftermath of the storm, and Magness was fired.

Additionally, ERCOT has announced plans to better manage large-scale power outages going forward. Some efforts, such as winterizing the physical grid infrastructure, will more likely come from the state Legislature, ERCOT adviser Cliff Lange said. Others, he said, will be dictated by the Public Utility Commission of Texas, the regulatory body that oversees ERCOT.

“We have one major regulator with the Public Utility Commission, and that independence has been jealously guarded, I think, both by policymakers and by the industry and ERCOT,” Magness said in an informational video published by the council.

Ramanan Krishnamoorti, a chemical engineering professor and chief energy officer at the University of Houston, said ERCOT’s longstanding independence also came from the state’s desire to avoid federal interference in its power grid.

“If you go national, you have the federal government putting its full force behind it—of rules and regulations,” he said. “So the Texas uniqueness has really sort of stemmed from the idea that they did not want the federal government to dictate what happens with generation and distribution of electricity.”

While the state continues to make changes, cities and businesses will continue day-to-day operations to ensure safety during the next major event.

“We learn something at every storm,” Baumgartner said.