Real estate agents have experienced a new hurdle amid the pandemic: buyers making a decision after a virtual tour, then backing out once they see it in person.

Potential homeowners can look at homes via video tour or FaceTime, but the experience of walking inside a home cannot be replaced virtually, said Steve Spicer, a Houston-area Realtor who manages a team of agents in the Clear Lake area. A buyer might back out based on factors they could not see virtually, from the drive into the neighborhood and appearance of area homes to local road conditions, he said.

“They feel at home when they have found the home, and you don’t get that benefit from doing it via video,” he said.

While Spicer said the virtual aspect of selling homes during a pandemic has been useful in some ways, it has complicated the process in others. Some buyers will tour only vacant homes, and many photographers or other support team members will not go into a property if the seller is still in the house.

“When I walk into a house, or any agent walks into a house, they don’t know who’s been there and how careful they’ve been or not been,” he said.

Home touring, buying goes virtual

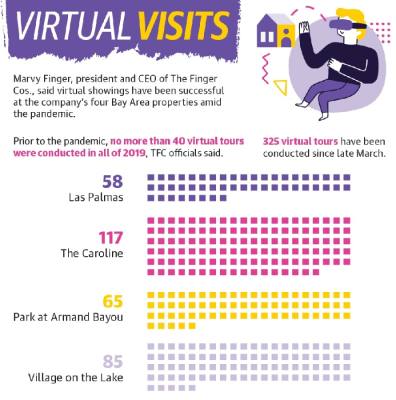

Marvy Finger, the president and CEO of property developer The Finger Cos., said in an email to Community Impact Newspaper the popularity of virtual tours has exploded at the four luxury housing communities in the Bay Area. Most people, though, still prefer an in-person tour with the new safety precautions in place, Finger said.

“On average, about 75% of prospective residents prefer to physically tour the property at some point prior to signing a lease, whereas approximately 25% are comfortable with taking a virtual tour by itself before signing on the dotted line,” he said via email.

During in-person tours, every staff member and prospective resident wears a face mask at all times and adheres to proper social distancing guidelines. The leasing office, common areas and models are thoroughly cleaned and sanitized between tours as well as multiple times a day, and staff and prospective residents are asked to avoid touching surfaces in models and common areas, Finger said.

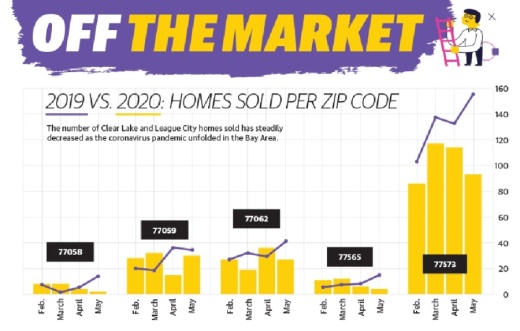

Spicer said from mid-March to the end of April, he saw a 25% decrease in the number of new Houston-area listings. Houses are being removed from the market, with sellers not wanting extra foot traffic in their spaces and being unsure about their employment status.

Virtual homebuying can create issues in marketing and selling a home: When a virtual buyer takes a house off the market, then cancels the contract, the number of days a property has been on the market is not reflective of the home’s actual market condition, Spicer said. Homes that have been on the market for longer are generally stigmatized, he added.

Despite the challenges of closing the deal on a home through an all-virtual process, he said the shift to virtual and video tours has been a long time coming. Buyers being able to prescreen homes via video has been helpful for buyers, he said.

“We should have been doing this a long time ago; it’s just [that COVID-19] has forced our hand,” he said.

New workforce possibilities

The pandemic did not result in commercial office spaces being rapidly vacated, mainly because walk-ups are much more common in League City as opposed to multiple-story buildings, said David Hoover, the city’s planning and development director. The city is characterized by individually based companies in smaller commercial spaces, such as insurance offices or medical professionals.

While the ongoing nature of the pandemic makes it difficult to assess how commercial office spaces will be affected, Hoover said it could trigger an eventual shift away from the open-office concept that has become popular in recent years.

“Long term, people are going to remember this, and it’s probably not the last time it’s going to happen,” he said. “Even in the smaller-size buildings, I do think there’s going to be some changes going forward.”

As the pandemic forced City Hall to go virtual, Hoover noted a change in pace as conversations happened virtually. Hourlong Zoom meetings have replaced multiple days of in-person meetings in his line of work, and people will remember this when it comes to forming a post-pandemic workplace, he said.

League City is in a secure financial place, he added, because commercial development in Pearland, Webster, and the general southeast Houston and NASA areas has not experienced any pandemic-related slowdown. Some larger projects, such as the Alamo Drafthouse coming to League City, have had target dates extended, but smaller projects have remained on schedule, he said.

Scott Livingston, the city’s director for economic development, said the next year to 18 months will be uncertain, making it difficult to predict how the real estate market might react. However, he said the investors and businesses with “the long perspective in mind” can still try to make gains by planning and taking advantage of the opportunities present now.

“None of us have a crystal ball,” he said, “[but] this is Texas; this is the Greater Houston region. ... We do not take positions of defeat. We’re going to figure this out one way or the other.”

Shifting from ‘bedroom’ status

Spicer said as more people work from home, they have different needs for space. Generally, homeowners have been selling smaller spaces to purchase bigger ones, and homeowners are more willing to move farther from their work centers if they have a remote option.

“That’s going to be a huge game changer,” he said.

Livingston predicted a U-turn in the maximizing of density and building the “urban core”; like Hoover, he expects a renewed push for commercial investment in the suburbs. Additionally, he said there will likely be a new look at office rents, especially if people can work from home and reduce the amount of necessary office space.

People have formed new habits during their time working remotely, and this will result in different desires for corporate spaces once Bay Area workers are able to return to their offices, Livingston said. More than eight in every 10 full-time workers who reside in League City commute outside the city to their place of employment, according to city data, he added.

Office spaces themselves will evolve to be more spacious and allow for social distancing but also will likely evolve to include more greenery and aesthetically pleasing aspects, Livingston said.

“If people are going to spend time away from home, there has to be something that attracts them to that space,” he said.

The underlying push toward working near or from home could accelerate League City’s shift from a “bedroom community”—one where a significant portion of workers commutes to an employer outside the city—into a suburban one, with more primary, locally based employment in the same community where people live, Livingston said. While this shift may have taken decades prepandemic, he said it could now happen in a matter of years.

Moreover, community identity may become increasingly important as workers return to their offices. Patronizing local businesses will create new possibilities for business growth and foster community pride, Livingston said.

Hoover agreed.

“When folks are out developing buildings, there might be a propensity to do ... more smaller things in suburbs,” he said. “Downtown [Houston] isn’t going away, but there will be a shift moving forward.”

Regional collaboration will still be necessary for the health of the Bay Area and the Greater Houston region, Livingston added, encouraging residents to remember isolation is not the answer.

“We can’t all just pull up the drawbridges. ... There’s a limit,” he said.

As local communities find ways to stabilize and create a new normal amid the effects of the pandemic, Livingston said a positive domino effect is likely to happen. The Bay Area has the potential to emerge from the pandemic more economically competitive than before, he said.

“Stability will also give us diversity—and I’m talking about in every sense of the word—and also make us more globally competitive as a region,” he said.