On Oct. 30, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Texas General Land Office released the Coastal Texas Study, which proposes several projects to protect Galveston Island, the Bolivar Peninsula, Galveston Bay and the rest of the coast from storm surge flooding caused by hurricanes.

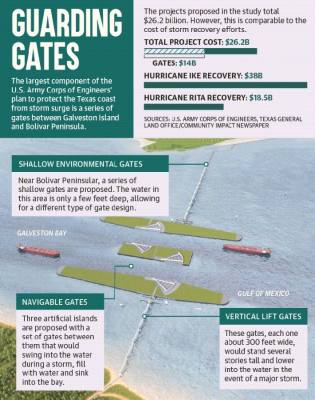

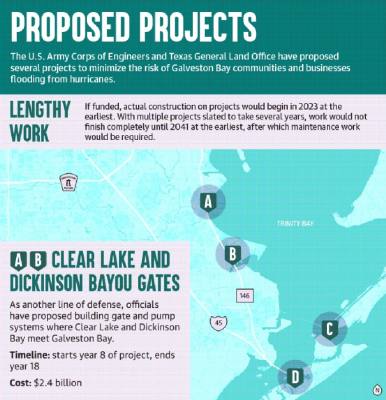

The study calls for $26.2 billion worth of projects, including building gates between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula; constructing miles of beaches and sand dunes along Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula; creating a ring barrier system of various defenses around Galveston Island; building gate systems and pumps at Clear Lake and Dickinson Bay; and conducting “nonstructural improvements,” such as home elevations, along the west side of the bay.

The study will go before U.S. Congress in the summer, and, pending funding, work would begin as soon as 2023. It has been over a decade since the idea of a coastal barrier was first proposed, and local officials are excited to see the study close to potential funding, especially considering recent storms.

In September, Tropical Storm Beta dropped up to a dozen inches of rain on the area while also causing coastal storm surge, giving the creeks nowhere to drain, officials said.

“Every day we delay keeps us at risk,” League City Mayor Pat Hallisey said. “When we get a coastal surge of 10 feet or above and inland rain, we’re all going underwater.”

Multibillion-dollar, decadeslong plan

In addition to dealing with COVID-19, Texas saw an active hurricane season in 2020. While no hurricanes hit Texas directly, residents across the coast want to see protection before another Hurricane Harvey or Ike strikes, Army Corps Col. Tim Vail said.

“There’s definitely a sense of urgency,” he said. “We’ve had some very close calls.”

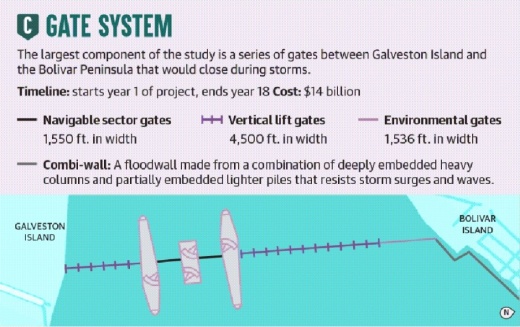

The study’s proposed projects include two large sector gates between three artificial islands that would be constructed between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula. These gates would swing closed from the islands, according to the the Corps and the GLO.

Adjacent to the large gates, a series of 15 vertical lift gates, each about 300 feet wide, would be installed. They would lower into the water in the event of a storm to hold back water as well.

To the north, where the water is 5 feet deep or less, about 1,500 feet worth of shallow environmental gates would be installed. In all, the different types of gates would work together to protect the about 7,500-foot channel between the island and peninsula.

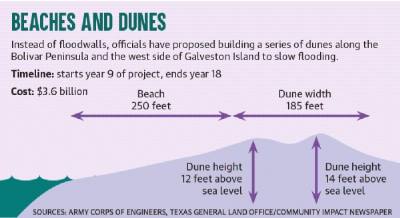

Additionally, the Corps and the GLO have proposed building a series of beaches and sand dunes to protect the coast—particularly the peninsula and the west side of Galveston Island. A total of 39 million cubic yards of sand—17 million for Galveston Island and 22 million for the Bolivar Peninsula—would be required to build the beaches and dunes, officials said.

Contractors would build beaches 250 feet back from the water’s edge and then build two dunes totaling 185 feet wide—a 12-foot-high dune and a 14-foot-high dune behind it. The dune option is more environmentally acceptable and aesthetically pleasing than floodwalls, according to the Corps and the GLO.

Other proposals include a 15-mile Galveston ring barrier system—a series of walls, gates, levees and pumps surrounding the back side of the island to protect it from flooding. The proposals are a result of years’ worth of ideas and adjustments to residents’ and other stakeholders’ feedback, said Mark Havens, the GLO chief clerk and deputy land commissioner.

“We’re here today to say: We heard you,” he said. “There have been numerous changes to this study.”

In addition, the study proposes improving the existing Galveston seawall. A gate system with pumps would be built where Clear Lake and Dickinson Bay reach Galveston Bay as a second line of defense from coastal flooding. About 1,750 residences along the west side of the bay in various cities, such as Seabrook and La Porte, would be elevated to minimize flood risk, and ecosystem restoration efforts would be made up and down the coast, according to officials.

The projects proposed in the study total $26.2 billion. However, this is comparable to the cost of storm recovery efforts: It cost $38 billion for the coast to recover from Hurricane Ike in 2008 and $18.5 billion to recover from Hurricane Rita in 2005, officials said.

If the proposed projects are constructed, they would result in about $2.3 billion in equivalent annual benefits. During a 100-year storm, there would be about a 77% reduction in damaged structures and about a 66% reduction in flooded critical infrastructure, officials said.

Local politicians have said the coastal barrier and its funding is a priority for the 87th Texas Legislature, which began Jan. 12.

“The coastal spine’s a huge priority not just for our region, but it has a huge national economic impact and [importance], so we’re all certainly supportive of that,” said state Rep. Greg Bonnen, R-Friendswood.

Additionally, experts are confident the plan is “truly competitive” for federal investment, Vail said. If funded, the projects would be constructed over 12-20 years, and to-be-determined local sponsors would help maintain the projects, such as the dunes.

Environmental concerns

While Army Corps and GLO experts and politicians are anxious to see the project underway, several local environmental groups and experts have opposed entire portions of the coastal barrier plan.

Representatives from Bayou City Waterkeeper, Galveston Bay Foundation, Rice University and Turtle Island Restoration Network as well as other environmental experts have all spoken out against some proposed projects, saying they are more expensive than necessary and harmful to the environment.

Of the $26.2 billion in projects, over half—$14 billion—would fund the gate system. The gates would dramatically affect the flow of water in and out of the Galveston Bay, and its environmental impacts have not been studied, coastal ecologist Azure Bevington said.

“There’s a lot of questions that haven’t been answered,” she said. “There’s so many what-ifs about how this will function based on the sedimentation and hydrodynamics that we experience.”

Nonstructural improvements, estimated at $220 million, should be considered everywhere in the Bay Area, Bevington said, as they could be cheaper than and even eliminate the need for the $14 billion gate system.

If the plan is approved, nonstructural improvements would not begin until 14 years after the start of the overall project, according to the Corps’ timeline. They need to happen earlier because they are cheaper and faster while providing adequate benefits, Bevington said.

“That they left this ... [measure for] last shows me that they do not have the coastal communities’ welfare in mind,” she said. “This is easy and cheap compared to the rest of this, and it should be first.”

Additionally, if approved and funded by Congress, the proposed beaches and dunes would not be constructed for 10-15 years, Bevington said.

“We need projects that are more realistic to be built sooner,” she said.

Bevington said experts conducting the study need to consider the advantages of looking at each potential project individually instead of tying it all together in a single, large plan.

Environmentalists have also indicated concerns about how the projects would affect commercial and recreational fisheries, shellfish, dolphins and other marine life. According to Scott Jones, the government and regulatory affairs manager for the Galveston Bay Foundation, the Corps has said it has not completed environmental studies and will not do so until Congress approves the plan, after which environmentalists will have less influence on the plan.

“This is a big problem,” Jones said.

Commercial and recreational fisheries account for one-third of fishing activity in Texas. The gate system will affect them as well as marine life, so environmentalists need details before the project is approved, he said.

Naomi Yoder, a scientist for Healthy Gulf, said the Corps’ plan could result in a 7% decrease between low and high tides, and salt marshes depend on high tides. Additionally, it could limit the water exchange into and out of the bay by up to 6%.

“That’s enough to starve a marsh and a shrimp fishery,” she said.

Jordan Macha, the executive director of Bayou City Waterkeeper, said projects should be tailored to communities.

“Protecting our communities is critical, but we can’t rely or wait on a silver-bullet solution that will take decades to build and can cause [significant] risk and harm to the bay,” Macha said.

Galveston Bay Park

A separate proposal to build a 25-foot-high wall through Galveston Bay along with manmade islands to protect the area from flooding is meant to complement the proposed coastal barrier.

Jim Blackburn, co-director of the Severe Storm Prediction, Education, & Evacuation from Disasters Center at Rice University, said the SSPEED Center in 2009 was given a grant to study the effects of Hurricane Ike. In 2015, the SSPEED Center came up with the concept of Galveston Bay Park.

The idea includes widening the Houston Ship Channel hundreds of feet and using the clay from the widening to build a 25-foot-tall barrier along the channel from its mouth up north to Texas City down south.

“It’s a multipurpose flood protection concept,” Blackburn said, noting the project would protect cities such as Seabrook and Kemah while also protecting petrochemical and other industries.

Additionally, miles of artificial islands would be built along the wall. These would give residents easier access to Galveston Bay, which normally can only be accessed with a boat, Blackburn said.

“This has the chance to really open up Galveston Bay to the public,” he said.

Blackburn said Galveston Bay Park could eliminate the need for the Clear Lake and Dickinson Bay gate systems included in the Coastal Texas Study but would complement the rest of the Army Corps’ plan. Even with the gates between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula, communities on the west side of the bay are at risk of flooding, but Galveston Bay Park could mitigate those risks, Blackburn said.

The SSPEED Center is working with the Corps on the project, and the Corps has officially indicated the park would work with the coastal barrier project. The idea is to have multiple lines of defense, Blackburn said.

The park will go through another round of studies to determine its feasibility. If the project is feasible, local governments will consider ways to permit and fund the project, with construction beginning as early as 2025, Blackburn said.

Blackburn said he supports the coastal barrier and said the park is not a competitor.

“I think it is a needed project,” he said of the barrier project. “We need protection as soon as we can.”