On Nov. 19, representatives from Bayou City Waterkeeper, Galveston Bay Foundation, Rice University, Turtle Island Restoration Network and other environmental experts hosted a presentation on the Coastal Texas Study, the study by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Texas General Land Office on how to protect Galveston Bay and its communities during major storms.

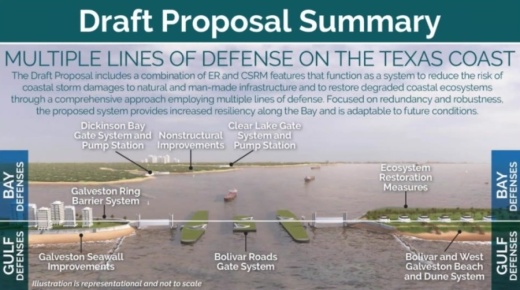

The proposed $26.2 billion plan calls for two miles of gates between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula; a ring barrier of various levees and walls surrounding Galveston Island; the creation of miles of beaches and dunes along the shore; gate systems at Clear Lake and Dickinson Bay; improvements to the existing seawall; and “nonstructural improvements,” such as home elevations.

Of the $26.2 billion in projects, over half—$14 billion—would fund the gate system between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula. Environmentalists said this would dramatically affect the flow of water in and out of the Galveston Bay, and its environmental impacts have not been studied, according to coastal ecologist Azure Bevington.

The miles of gates leave a lot of room for error, which has raised questions among environmentalists, Bevington said: "Could sediment run up against the gates or their pillars and potentially make the gates malfunction? What happens if the gates malfunction while closed and are not able to be opened back up for days or weeks?"

“There’s a lot of questions that haven’t been answered,” Bevington said. “There’s so many what-ifs about how this will function based on the sedimentation and hydrodynamics that we experience.”

The proposal for the beaches and dunes is to bring in millions of cubic yards of sand and create longer beaches toward the water, and then, to create dunes away from the water to protect the coast during storms. Residents enjoy easy access to the bay’s water, which makes such an idea unappealing to some, Bevington said.

“This is not realistic for this part of the Texas coast,” she said.

Additionally, if approved and funded by Congress, the beaches and dunes would not be constructed for 10-15 years, Bevington said.

“We need projects that are more realistic to be built sooner,” she said.

The plan also calls for areas along the west side of the bay to receive nonstructural improvements, such as flood-proofing buildings and elevating homes. The cost of this effort is $220 million—still a lot, but only a fraction of the overall price of the project, Bevington said.

Nonstructural improvements, she said, should be considered everywhere in the Bay Area, as they could be cheaper than and even eliminate the need for the $14 billion gate system between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula.

“I really think this should be a model for communities that are located on the coasts,” Bevington said of nonstructural improvements.

If the plan is approved, nonstructural improvements would not begin until 14 years after the start of the overall project, according to the Corps’ timeline. However, Bevington said, they need to happen earlier because they are cheaper and faster while providing adequate benefits.

“That they left this ... [measure for] last shows me that they do not have the coastal communities’ welfare in mind,” she said. “This is easy and cheap compared to the rest of this, and it should be first. There’s no excuse whatsoever for that not to come first.”

Bevington said experts conducting the study need to consider the advantages of looking at each potential project individually instead of tying it all together in a single large plan.

As for the cost, Bevington said, it will eventually come back on Bay Area residents. The federal government will pay for a portion, and the state—or a taxing jurisdiction, which has yet to be created—will fund the local share. This means that the $26.2 billion will come back to Bay Area taxpayers.

In addition to project concerns, environmentalists have indicated worry about how the projects will affect fish, shellfish, commercial and recreational fisheries, dolphins, turtles, birds and other marine life. According to Scott Jones, government and regulatory affairs manager for the Galveston Bay Foundation, the Corps has said it have not completed environmental studies and will not do so until Congress approves the plan, after which environmentalists will have less influence on the plan.

“This is a big problem,” Jones said.

Commercial and recreational fisheries account for one third of such activity in Texas. The gate system will affect them as well as marine life, so environmentalists need details before the project is approved, he said.

Naomi Yoder, a scientist for Healthy Gulf, said the Corps’ plan could limit the water exchange into and out of the bay by up to 6%.

“That’s enough to starve a marsh and a shrimp fishery, for example,” she said.

Additionally, the plan could result in a 7% decrease between low and high tides, and salt marshes depend on high tides. The Corps expects the plan to affect 1,148 acres of marshes, and their response, Yoder said. is not meant to protect those marshes but to use other marshes as surrogates for restoration. This, she said, is not adequate.

Jordan Macha, executive director Bayou City Waterkeeper, said projects should be tailored to communities.

“Protecting our communities is critical, but we can’t rely or wait on a silver bullet solution that will take decades to build and can cause [significant] risk and harm to the bay.”

Macha encouraged concerned residents to go to bit.ly/barrierextension to request the Corps extend its public comment portion on the proposed plan from Dec. 14 to Feb. 1. An extension would give groups and individuals more time to review the complex plan report and respond, Macha said.