Clear Creek and Dickinson Bayou, two major bodies of water in the area, have been studied several times over the decades by various groups, including the Army Corps of Engineers, League City City Manager John Baumgartner said. A few times, officials have tried to push for projects along these waterways to address flooding issues, but due to conflicting objectives or a lack of consensus, nothing ever happened—until now.

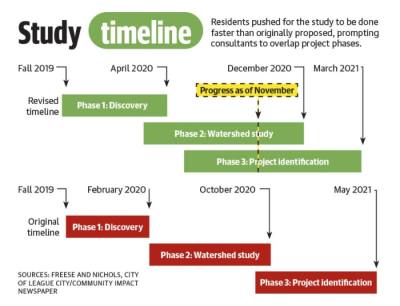

Since November 2019, consulting firm Freese and Nichols and League City officials have been studying both the lower portion of the Clear Creek watershed and all of the Dickinson Bayou watershed. The goal of the study—which has buy in from several cities in the area, including Pearland, Friendswood, Webster and others—is to determine projects that could alleviate flooding both watersheds experience during heavy rainfall, benefiting the southeast Houston area, officials said.

The study is getting close to wrapping up, and final project ideas will soon be proposed.

“Everybody knows we need to do something,” Baumgartner said. “It just wasn’t clear what something was when we started this initiative.”

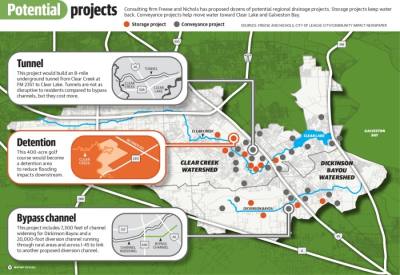

Potential projects

While the study is not yet complete, officials have identified some early potential projects for consideration, Freese and Nichols Project Manager Brian Gettinger said.

Along Clear Creek, officials have identified 18 conveyance-related projects and nine storage projects. Meanwhile, there are nine conveyance-related projects and four storage projects along Dickinson Bayou.

Conveyance projects help move water through an area, such as a bypass channel. Storage projects, which have more benefit upstream, hold water in a place for a time until it slowly drains out, such as a detention pond, Gettinger said.

Probably the most unusual proposed projects are underground tunnels which would run for miles beneath League City, Friendswood, Webster and the Clear Lake area. The tunnels, at least 75 feet underground, would allow Clear Creek overflow to drop in at several points and be moved via pressure to an outlet, such as Clear Lake or Galveston Bay, Gettinger said.

“A tunnel can do the same thing [as a surface bypass channel] but without the impacts,” he said. “The question is: Is that a solution that is appropriate for Clear Creek and/or Dickinson Bayou?”

According to a map consultants shared, one tunnel would run 8 miles from FM 2351 at Clear Creek to Clear Lake. Gettinger said tunnels are minimally disruptive and allow for less property acquisition than would building bypass channels on the surface, but they are expensive, he said.

Resident Dave Johnson, an alternate on the Dickinson Bayou Watershed Steering Committee, which is a group comprising several cities researching flooding solutions, said he is pleased with the study’s progress. While some think building tunnels is “crazy,” learning cities such as San Antonio have successfully implemented them made him realize they are realistic, despite the expense.

“There’s some pluses with a big-dollar concept,” he said.

Storage projects include large detention areas on the upstream portions of Clear Creek and Dickinson Bayou. Freese and Nichols is also considering widening both channels to avoid them overflowing into nearby streets and residences.

“We’re focused on really large-scale projects,” said Jim Keith, technical lead with Freese and Nichols. “We’re really focused on some out-of-the-box unique concepts to move more water.”

While there are several projects officials are considering, none of them are enough to solve flooding alone. It takes several projects working together in sequence to provide full benefits, League City Project Manager Anthony Talluto said.

The next step is to apply the projects to a 2D rainfall simulation model the group has developed to see how effective they are at reducing flooding.

“We’re getting close to the solution sets at this point,” Gettinger said.

Modeling benefits

Freese and Nichols officials have been using 2D modeling to simulate how neighborhoods and areas along Clear Creek and Dickinson Bayou flood.

Older regional flood studies, such as those done by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, used 1D modeling to look at cross sections of rivers and bayous to see how they flood during heavy rain. However, 2D modeling goes a step further to show not only how much water flows outside of the rivers and bayous, but also where it goes: streets, neighborhoods, ditches and more, Keith said.

“It’s important to stress we spent a lot of time and a lot of money on the model,” Gettinger said. “It’s really critical to have that.”

The modeling is based on hydraulics and hydrology. Hydraulics deals with calculating the depth of flow in open channels, and hydrology is related to the quantity of water runoff generated within an area. Both help experts predict how rainfall would affect the landscape and estimate how deep flooding would get in certain areas during hypothetical storms, Keith said.

Additionally, officials are using Atlas 14, a recent study of historical rainfall data that redefines and increases the severity of 100- and 500-year storms, for the study. It is the best available rainfall data that has been developed, Keith said.

“We’re really leveraging the best available data that we have now to look at the hydrology ... of these two watersheds,” he said.

By using data of how areas flooded during Hurricane Harvey and other major storms, Freese and Nichols have fine-tuned the model to be more accurate, Gettinger said. The better the model, the more accurate its simulations and the more beneficial proposed projects can be, officials said.

The model has benefits beyond the study: If a large storm is brewing, cities can use the model to simulate how much rain it might drop on the area and how the area might flood, allowing cities to prepare and alert residents ahead of time, Gettinger said.

The model could also help cities identify neighborhood-specific projects too small to have regional benefits, officials said.

“This 2D modeling with Atlas 14 modeling ... will identify other areas in need of improvement,” Baumgartner said.

Freese and Nichols has been working on the model since about February, and work running proposed projects through the model should wrap up by the end of the year, Gettinger said.

Riverine vs. storm surge flooding

While Freese and Nichols’ work will result in projects to help alleviate regional flooding, it will not reduce all flooding.

The type of flooding Freese and Nichols is concentrating on is riverine flooding, or flooding that happens in Clear Creek and Dickinson Bayou when it rains. The projects implemented to address this will not necessarily help during storm surge flooding, which occurs when Galveston Bay and the bodies of water that drain into it rise due to wind pushing water inland.

To address storm surge flooding, Bay Area cities are banking on the Coastal Texas Study, which includes a potential project to build gates and other barriers in Galveston Bay to hold back water in the event of storm surge. The coastal spine project will go before Congress for federal funding in mid-2021, officials have said.

“We are still hopeful that something will evolve out of that,” Baumgartner said.

Freese and Nichols will present study findings and recommended projects in March, after which stakeholders will decide what projects to fund.

“We don’t want this to be another ... study that doesn’t go anywhere,” Gettinger said. “The whole point of this is to fix ... the problem.”