“It’s terrible,” City Manager John Baumgartner said. “It impacts all those softball players. There’s not an alternative place to play.”

During closed session Jan. 12, League City City Council discussed the business at 1150 Big League Dreams Parkway, which offers six baseball fields on which residents can practice and play. After convening in open session, City Council voted unanimously for the city to terminate its agreement with Big League Dreams due to safety concerns and delinquent payment.

Around 2004, League City partnered with Big League Dreams, which has other locations in Texas, California and Nevada, to build six baseball fields. Under the agreement, League City built the facility on city land, and Big League Dreams operated and programmed the facility while providing a yearly maintenance and operations fee to the city, along with 1% of gross revenue Big League Dreams made. Big League Dreams was also responsible for maintaining the facility in “first-class condition,” Baumgartner said.

“It’s like a long-term lease,” he said of the agreement.

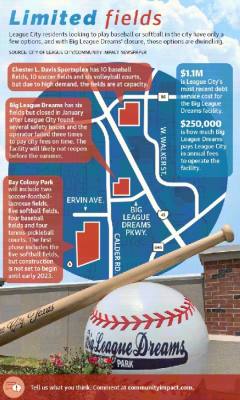

The debt League City pays each year for the facility fluctuates but most recently totaled $1.1 million. Meanwhile, Big League Dreams’ most recent annual fee paid to the city was about $250,000, meaning the facility operates at a loss, Baumgartner said.

The tradeoff is the city received additional fields on which residents could play, he said. The only other place in the city where residents can practice and compete is the Chester L. Davis Sportsplex, which has 26 fields, all at capacity.

Before COVID-19 hit, Big League Dreams was late twice paying the city its annual fee, due Sept. 30 of each year. In November, when Big League Dreams was late a third time, the city sent the company a notice of default, saying payment was late and the fields were not in good condition.

“We paid $30 million to set someone up in business, and they let us down,” Mayor Pat Hallisey said. “We don’t want that to happen again.”

Big League Dreams paid in early January but did not make fixes to the fields, leading the council’s decision to terminate the agreement, Baumgartner said. Big League Dreams’ owners declined to comment.

“The turf has reached its age,” Baumgartner said, also noting chairs and benches are broken, water meters are leaking, netting is torn, and more. “The list goes on. It’s pretty long.”

Steven Bahr is a League City resident who used the facility for years to play softball with his friends. While the sudden closure was surprising to some, Bahr said he was not shocked.

“Everyone playing there knew something was coming because of the lack of maintenance from Big League,” he said.

Athletes who were using Big League Dreams are now looking for facilities in Friendswood, Galveston or other nearby locations to continue playing. The League City location was nice because it was centralized; people from Houston and Galveston came to Big League Dreams to play together, Bahr said.

“It’s fun having it here in League City for sure,” he said. “If we do lose it, it’s a little bit of a hit to the gut after being there so long.”

Before February ends, the city plans to open a request for proposals for a new operator to reopen the facility by early summer. Big League Dreams will likely offer a proposal, but it is likely the facility will eventually operate under a new name, Baumgartner said.

Whoever takes over the fields will have to pay about $2 million to get the facility in reasonable shape, he said. Those who used Big League Dreams will not be keen to return unless the facility is rejuvenated before opening, Bahr said.

The move has affected not only players who use the fields, but even businesses in the area, officials said. A Fairfield Inn & Suites across the street from Big League Dreams has already seen room cancellations due to the closure, Marketing Director Tejal Patel said in an email.

“We did build this hotel based on Big League Dreams being a major revenue channel for us,” she said. “The closing of BLD will impact our hotel by a revenue reduction of at least 40% during the summer months and 25% in the winter months.”

Other businesses in the area that profit from players may take a hit, officials said.

The city is working to build Bay Colony Park, which would include numerous new athletic fields along Ervin Avenue near Calder Road, but construction is two years away.

“It’s a hardship on everybody,” Baumgartner said. “Nobody wants to see the facility closed.”