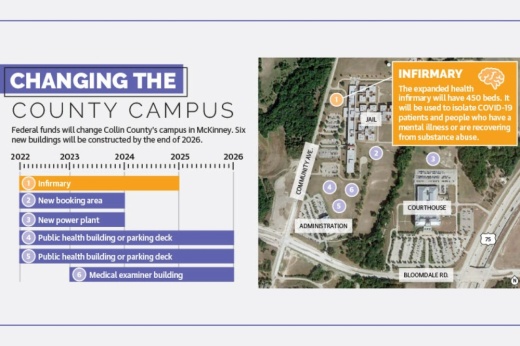

The facility, located on the Collin County campus at the corner of US 75 and Bloomdale Road in McKinney, is one of three county projects funded by the American Rescue Plan Act. That program provides federal funds meant for supporting public health and mitigating the spread of COVID-19.

With an expected completion date of 2025, the expansion will convert the 24-bed infirmary at the detention center to a 450-bed facility, according to the county’s 2021 COVID-19 recovery plan. About 75 of the beds will be dedicated to inmates who need detoxes from alcohol or other substances.

The county has selected an architect for the $134.1 million building, and officials are in bimonthly meetings with county staff to nail down the project scope. County Administrator Bill Bilyeu said the project will go out to bid in fall or winter of this year to begin construction.

Identifying the need

Collin County received just under $201 million from the American Rescue Plan Act’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. County commissioners approved these funds in August to be used for infrastructure that not only supports public health, but also “people with barriers to services,” the plan stated. This group includes people of color, low-income families and those with limited English proficiency.

County officials considered comments from community members during commissioners’ meetings when deciding how to use the federal funds, according to the recovery plan. Frequent topics of discussion were COVID-19 contact tracing and the mental health of both the general public and inmates at the jail, the plan stated.

Community input coupled with trends observed by county officials led to the decision to expand the jail’s infirmary.

“When we were trying to separate out people that either were testing positive for COVID[-19] or had close contact, it was hard to get them isolated out, and that made us really recognize even more so how small our infirmary was,” Bilyeu said, adding that many county jails also use their infirmaries for mental health purposes.

The county’s recovery plan referenced the need to socially and physically distance inmates due to the pandemic. Personal quarantines and isolation also resulted in an “unprecedented escalation” of the opioid epidemic, the report stated.

“[The opioid addiction] crisis not only burdens the families and individuals of those suffering from an addiction disorder, but it also overwhelms the treatment capacity of the Adult Detention Center infirmary when these individuals are brought to the jail,” the recovery report stated.

About 25% of the county’s average daily inmate population have mental health needs, according to a county analysis that spanned from 2015-19. These needs include people on court-ordered medication, any level of suicide watch or alerts for mental illness, according to the report.

Schizophrenia is one of the most common mental illnesses seen in the jail, LifePath Systems Director Tammy Mahan said. LifePath Systems, the county’s designated behavioral health and disabilities authority, collaborates with the jail and its staff psychiatrist.

People who have schizophrenia interpret reality abnormally, and symptoms of the disorder range from hallucinations to disorganized thinking and speech, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Mahan said that the way schizophrenia symptoms manifest cause people with the disorder to frequently be charged with lower-level crimes.

“That’s one of those issues we’ve been trying to work with, both with all of our local law enforcement as well as the jail and the sheriff’s department, [to divert] those people,” Mahan said. “If they’re not a danger to the community and a terrible crime wasn’t committed, if there’s any way [law enforcement] cannot arrest them, [it is better to] take them into one of our services [instead].”

Diversion and treatment options

The Collin County Sheriff’s Office is one of the local law enforcement entities working with LifePath Systems on jail diversion.

When a deputy sheriff responds to a call involving someone who may need mental health services, they have options depending on the severity of the situation, said Sheriff Jim Skinner. A deputy sheriff may provide referral information to the person or family, help the person with voluntary admission into a treatment facility or arrest the person, when justified.

“All peace officers have a duty to divert a person from the county jail to an appropriate treatment center when it’s safe,” Skinner said in an email.

Texas peace officers, which include police officers, deputy sheriffs and constables, receive training on crisis intervention, a methodology intended to de-escalate and assist people experiencing a mental health crisis.

Skinner said crisis intervention training consists of learning about commonly encountered mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia, personality disorders, mood disorders and developmental disorders. It also includes effective communication skills for a person who may be in crisis as well as statistics and facts debunking myths about mental illness.

Collin County has deputy sheriffs with additional specialty training who respond to calls involving a person in a mental health crisis on a 24/7 basis, Skinner said.

In the event that a person is arrested, officers and various medical professionals screen people during the booking process, Skinner said. Staff screen each person for signs of mental illness or disability, risk of suicide and any special medical needs. In some cases, a person is sent to an emergency room for more specialized assessment or care.

The faster the county is able to move a person with mental illness through the criminal justice system, the better, Mahan said. This is one of the reasons why screening is important.

“The longer somebody’s in jail, the more unstable their community life becomes,” Mahan said. “For example, people lose their apartments. So when they do get released after 200 or 300 days, they’re now homeless, whereas before they weren’t homeless.”

LifePath has had a jail diversion program for several years that assists people who have previously been in jail so they do not return. This year, the organization opened its Living Room as a proactive approach.

The Living Room is one of the places law enforcement can bring people who need mental health services, Mahan said. People can also come to the resource center, located off of Redbud Boulevard in east McKinney, on their own terms. Staff at the Living Room help people with job and housing placement, food access and more.

“The thing we obviously don’t want is that people go to jail just to get services,” Mahan said.

A reimagined campus

Until the new infirmary is built, Bilyeu said the county will manage like it has for the past 25 years.

Bilyeu added that once the expansion is complete, it likely will not be staffed with the expectation of all 450 beds being filled.

“When the county has its 3 million people, that infirmary is already right-sized for that, so we would never expect it to fill up anytime in the near [future],” Bilyeu said. “We’ll open it in stages, more than likely.”

Skinner echoed Bilyeu’s sentiments, adding that keeping up with the county’s growth is important.

“A community should take care of persons with a mental illness, an intellectual or developmental disability, or similar special needs,” Skinner said in an email. “This infirmary will substantially benefit the county because the current detention infirmary has just 24 beds, which is insufficient in light of the growing population.”

In addition to the infirmary, the county can look forward to two other projects from the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. A $54.8 million public health building and parking garage is planned for the southwest portion of the county campus, directly east of the county constable building. The third project is a $12 million medical examiner building, which will be next to the public health building. Both are expected to be completed by 2026.

“The benefit for the court making a good, quick, decisive answer [on use of the funds] is it’s helped us keep moving this stuff along,” Bilyeu said.