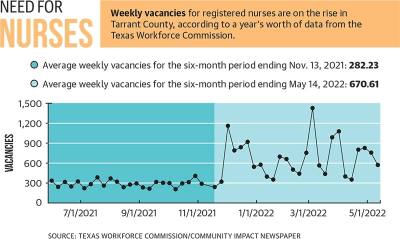

The average number of weekly vacancies for the six months ending Nov. 13, 2021, was about 282 registered nurses, data showed. That compares with the more than 670 average number of weekly vacancies in the six-month period that ended May 13, 2022.

The numbers are part of a larger trend in nursing shortages that began long before COVID-19, experts say.

“The health care workforce is at a critical standpoint,” said Stephen Love, president and CEO of the Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council. “The COVID-19 pandemic took a very heavy toll on health care teams, especially on the front lines. As a result, many have suffered stress, trauma, burnout and behavioral health challenges.”

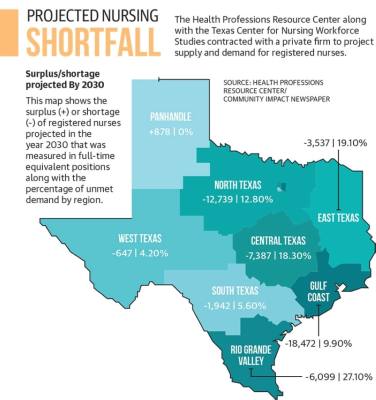

A 2018 study from the Texas Center for Nursing Workforce Studies projects that the state will be short nearly 60,000 nurses by 2032.

Ways to recruit, retain

Efforts are underway on numerous fronts both locally and at a broader level to take care of those nurses who are still on the job and to recruit more to join the profession.

“We have a focus to hire and retain team members who fill direct patient care roles, like registered nurses,” said Melissa Winter, interim president and west region chief nursing officer at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Grapevine.

The Texas Nurses Association has several programs in place to help. Its Nursing Shortage Reduction Program incentivizes schools to produce more graduates. The association also contributes to a Faculty Loan Repayment Program.

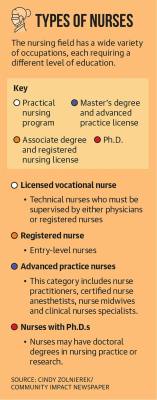

“The nursing shortage has two prongs to solve it,” said Cindy Zolnierek, CEO of the Texas Nurses Association. “One is producing more nurses, and the other end is keeping them. I think health care organizations are doing a lot to try to support particularly diverse staff because if they support their staff, they’re likely to be loyal and want to stay with that organization. So there is a return on investment there.”

Love and Zolnierek both said the average age of nurses today and a shortage of nursing professionals in academia leave room for further shortages in the field.

“The work environment during COVID[-19] was so intense and so difficult for nurses that some are leaving nursing, or they may be taking a temporary break,” Zolnierek said. “Some are of an age where they’re able to retire or retire early, and we don’t fully understand the impact of that.”

Love said a lack of nursing school faculty is also hurting the profession.

“So many qualified applicants ... for baccalaureate and graduate programs can’t really get accepted in nursing school for lack of the faculty that’s needed [to teach them],” Love said.

Many hospitals and professional organizations are offering support to those interested in entering the nursing workforce through grants and scholarships.

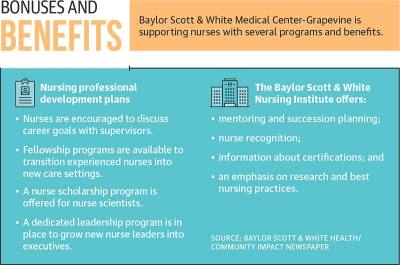

Baylor Scott & White Health offers professional development plans for its nurses, which includes scholarships for nursing sciences, fellowship programs to transition nurses into new care settings and discussions on career goals, according to Matt Olivolo, who is a Baylor Scott & White Health marketing and public relations consultant.

“At Baylor Scott & White Health we have multidisciplinary teams focused on workforce solutions,” Olivolo said in a statement. “We continue to invest in our workforce, including offering competitive hiring bonuses for critical positions. Additionally, we recently made a significant investment—totaling more than $164 million—by increasing the take-home pay of more than 12,000 frontline employees in nursing care roles.”

Because of these efforts, officials at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Grapevine said their facilities are staffed appropriately.

Zolnierek said now is a good time for young nurses to enter the workforce.

“Pre-COVID[-19], not all new graduates were finding jobs in hospitals,” Zolnierek said. “Now there are all kinds of opportunities.”

Traveling nurses

To help fill gaps in the workforce, hospitals have tapped into supplemental staffing through agencies, something Zolnierek said hospitals have done on a smaller scale for decades.

Zolnierek said traveling nurses, or agency nurses, can often earn twice as much as staffed nurses because of the shorter assignments. That practice not only puts strain on the hospitals, but can also create resentment among the nurses, she said.

“It became a vicious cycle where nurses were leaving hospitals to travel because they could make more money and have different experiences and travel to different places,” Zolnierek said. “In turn, it made the shortage in hospitals worse. So it increased the demand, which made the rates go up, which attracted more nurses to go to traveling [nursing] rather than stay in their hospitals.”

Traveling nurses have been invaluable through the pandemic and will continue to be, Love said.

“We’re not faulting nurses for wanting to have that mobility, the ability to travel or to [become traveling nurses] for their personal economic point of view,” he said.

Focus on mental health

With the high demands and trauma that nurses have experienced during the pandemic, both Love and Zolnierek said burnout has become a serious concern.

“We’ve seen increased suicide among many different health care professions, and there’s an increasing attention beyond burnout,” Zolnierek said.

A study done in 2019, before the pandemic, from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that “up to 54% of nurses and physicians and 60% of medical students and residents in the U.S. have symptoms of burnout—high emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or low sense of personal accomplishment from work.”

Many professional groups, such as the Texas Nurses Association, as well as hospitals and the Texas Hospital Association, are paying attention to health care workers’ mental health, Zolnierek said.

The National Academy of Medicine has drafted a study on clinicians’ well-being and resilience.

The study suggests several changes to help reduce burnout, including investing in more routine assessments of workforce stress and destigmatizing and supporting mental health. The study also recommends institutionalizing well-being as a long-term value and recruiting and retaining a diverse health workforce.

“Let’s not wait until we get to burnout,” Zolnierek said. “We’re looking at how we can support the well-being of our workforce so that they don’t get to that point.”