Since the coronavirus pandemic began in March, the number of people seeking assistance from nonprofit GRACE has increased nearly 40%. Among its clients is 60-year-old Grapevine resident Ale Reyes, who works two part-time jobs, as a cleaner and a cashier, to make ends meet. However, she said she still visits a food pantry a few times a year to feed herself and her family.

“It’s very hard,” she said. “But it’s the only way that you can survive as the head of the family.”

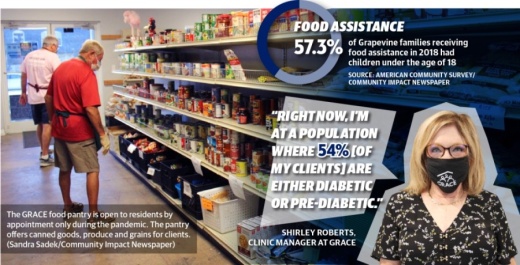

The city of Grapevine has a median household income of $85,722 and a poverty rate below 10%. Yet, as of 2018, around 57% of Grapevine families receiving food assistance had children under the age of 18, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey. This includes food stamps, receiving free or reduced-price school lunches or visiting food pantries.

The city of Grapevine has a median household income of $85,722 and a poverty rate below 10%. Yet, as of 2018, around 57% of Grapevine families receiving food assistance had children under the age of 18, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey. This includes food stamps, receiving free or reduced-price school lunches or visiting food pantries.Since the pandemic began in March, demand for food has increased. GRACE is a nonprofit in Grapevine that provides food, housing and medical assistance to people in need.

“It is a city that has pockets of people that are very food-insecure surrounded by pockets of people who are very wealthy,” GRACE Chief Program Officer Stacy Pacholick said. “You live in an area [where] you’re not getting food—the food that you need or the food that will keep you full—and yet, you look across the street and see the affluence that is right there.”

Defining food insecurity

The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines food insecurity as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods.”

Low food security is less about the quantity of food and more about the quality, variety and desirability, according to the agency.

Families are even more susceptible to food insecurity than individuals are, Pacholick said.

“[Parents] are more likely to try to give the food to the children than to themselves,” she said.

Food insecurity can be a product of several factors. Families may struggle with low wages, a lack of transportation or nearby grocery stores, and high medical or housing costs.

“They’ve got to pay for rent, and they’ve got to pay for utilities,” Pacholick said. “So they scrimp on what they’ll buy in food so that they can pay for these other things.”

An unhealthy diet can also lead to complications, including chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension.

“Right now, I’m at a population where 54% [of my patients] are either diabetic or pre-diabetic,” GRACE Clinic Manager Shirley Roberts said.

Soaring demand

Before COVID-19, mother of three Maria Guadalupe Flores used the GRACE food pantry every three months to feed her family, but limited walk-in hours and increased demands have made visitations harder.

Before COVID-19, mother of three Maria Guadalupe Flores used the GRACE food pantry every three months to feed her family, but limited walk-in hours and increased demands have made visitations harder.Many food banks and pantries like GRACE and the Tarrant Area Food Bank have adapted how they meet their communities’ needs while staying safe.

According to the TAFB website, the food bank distributed 60 million meals during fiscal year 2019-20, which ended Sept. 30.

TAFB President Julie Butner said the demand for food has been “so high” and lots of new people are coming for the first time.

“They do get embarrassed, and they are ashamed,” she said. “It’s heartbreaking. People now are beginning to understand we have people in our own city that are hungry.”

TAFB has increased distribution by 65% through its network of 350 partners and has added 35 emergency mobile food pantries per week to serve communities with increased levels of need.

Child hunger

According to data from Grapevine-Colleyville ISD, one in four children in the district are receiving free or reduced-price lunches as of Oct. 1.

“That number fluctuates yearly based on the number of approved applications,” said Julie Telesca, the GCISD director of nutrition services.

In 2018 and 2019, all GCISD pre-K students received free lunches based on a state waiver, which increased the student percentage those years. As of October 2020, all elementary and middle school students will receive free cafeteria meals through June 2021. Free curbside bundles are available to all children in the district.

According to Telesca, free and reduced-price meals are planned by the department’s registered dietitian, and meet USDA nutrition requirements. Meals include fresh fruit and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins and skim milk.

Dr. Erin Kane, a family physician at Baylor Scott and White Community Care, said issues of food insecurity affect not only the healthy development of children but also their stress level and their ability to concentrate in school. Children with food insecurity often struggle with their weight.

“We may find kids growing up in families that actually struggle with obesity because they’re eating unhealthy choices because that’s what the family has access to,” Kane said. “It can also lead to longer-term health outcomes that relate to obesity, such as as diabetes [and] high blood pressure.”

Free and reduced-price lunch programs are often a lifeline for some families to feed their children, making them even more crucial right now, Kane said.

“It’s clear that for most families, this is perhaps their healthiest meal of the day—and sometimes their most reliable meal,” she said.

Medical costs

Part of GRACE’s mission is to teach clients the importance of a nutritious diet, Roberts said. A healthy diet is often a luxury for many patients but is the best way to help people take control of their health.

Part of GRACE’s mission is to teach clients the importance of a nutritious diet, Roberts said. A healthy diet is often a luxury for many patients but is the best way to help people take control of their health.“If we can get people before they get all these chronic diseases, [...] we can possibly prevent them from getting diabetes,” she said. “Or, if they do get diabetes, it’ll be so controlled that they won’t require insulin.”

SanJuana Gutierrez has been diabetic for the past 30 years. Before receiving medical attention and a caseworker to help her with her diet, she said, she had no control over her diabetes and suffered from tooth loss and bad eyesight.

“Now that she’s in the GRACE clinic, she actually eats healthier, and they have helped her control everything,” said Gutierrez’ daughter, Juana Hernandez.

According to nonprofit Feeding America, Texans who suffered from food insecurity in 2019 spent over $200 more on health care annually than those who did not.

Certain costs can prove even higher if individuals are uninsured. A 2019 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranked Texas among the top five states with the highest per-capita health care costs associated with food insecurity.

Data from the American Community Survey shows 12.7% of Grapevine residents were uninsured in 2018.

“This problem has always been here,” Kane said. “We’re just doing a better job of identifying it and recognizing how pervasive hunger and food insecurity really is [... ] and how much it ties into a person’s overall health.”