She began by helping a dozen Bee Cave community members find appointments and was soon flooded with messages.

In late January, Wright launched Kendra’s COVID Coaches—one of several Central Texas volunteer groups working to aid the region in the pursuit of reaching herd immunity, or the status at which a community at large will have collective protection against a virus. Since January, grassroots groups such as Kendra’s COVID Coaches have played an integral role in connecting tens of thousands of Central Texans with vaccine appointments. Incoming requests to the groups have dwindled across April and May, however, and the groups’ approaches changed. Kendra said her team has shifted their focus to reaching residents who may be willing to get a vaccine but lack the urgency, time and access to obtain one.

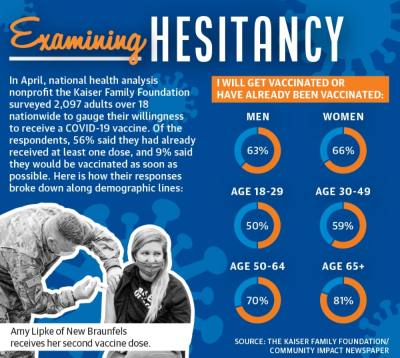

In a survey conducted by Sendero Health Plans across eight Central Texas counties at the end of 2020, 64% of respondents said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if they had the opportunity, and only 5.5% of respondents gave an unequivocal “no.”

Convincing those residents in the gray area is the goal for Central Texas health authorities, volunteer groups and physicians. Working in conjunction to reach these pockets of vaccine-hesitant Texans, they hope to boost vaccination rates past the threshold for herd immunity.

In light of emerging COVID-19 virus variants, there is pressure to reach that goal as soon as possible in what U.S. President Joe Biden has called a “life-and-death race.” As of June 7, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed around 42% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated. Some 51.6% of Americans have had at least one dose, a percentage Biden has said he aims to raise to 70% by July 4.

“The more we can reduce transmission right now, the more we reduce the chance of new variants, spreading and evading vaccination efforts,” Austin’s Chief Medical Officer Mark Escott said. The road to herd immunity

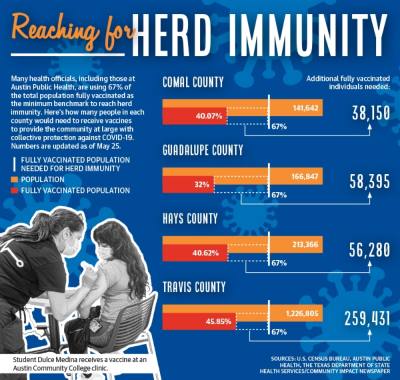

Officials at Austin Public Health have used 67% vaccination of the population as the minimum benchmark necessary to approach herd immunity. But the actual threshold remains unclear. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has estimated herd immunity will come at a higher rate of vaccination but at an April White House press briefing encouraged people not to focus on specific rates.

“We’ve made estimates that it is somewhere between 70% and 85%, but we don’t know that as a fact,” Fauci said. “So that rather than concentrating on an elusive number, let’s get as many people vaccinated as quickly as we possibly can.”

Other experts, including Dr. Lauren Ancel Meyers, executive director of The University of Texas at Austin’s COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, a network of researchers and epidemiologists, have said herd immunity is unlikely. Regardless, Meyers has said publicly that faster vaccination will help the virus subside by reducing the number of infections and community spread of the coronavirus and its variants. Coronavirus infections among fully vaccinated individuals is rare—only around 0.02% have proceeded to catch the virus in the Austin area, according to APH data.

While people who have contracted COVID-19 have antibodies against the virus and may contribute to herd immunity, Escott said they may not be as long lasting as antibodies from a vaccine and are around 20 times more likely to be reinfected with the virus than a vaccinated person.

Around 37.7% of Texans were fully vaccinated as of June 4. In Central Texas, Travis County leads in vaccination rates with nearly 48% of residents fully vaccinated.

Barriers and hesitation

The Food and Drug Administration’s May 10 decision to expand the Pfizer vaccine’s emergency use authorization to include 12- to 15-year-olds could help close the gap. Dr. Andrew Cavanaugh, a pediatrician with Chisholm Trail Pediatrics in Williamson County, said his patients have shown strong interest in getting their children vaccinated. Some have also expressed doubts or distaste in surveys, but Cavanaugh said the gradual ramping up of the vaccine’s availability gave patients time to warm up to the vaccine.

“I’m kind of glad that the supply has been the way it has. In some ways, I think it’s been beneficial because it has allowed a slow phasing in of this vaccine that people can kind of see what happened to the ‘guinea pigs,’ if you will,” Cavanaugh said.

Vaccine-hesitant individuals’ reasoning varies. Some cited logistical barriers, such as Betty Kent, a 65-year-old New Braunfels resident who runs a home-cleaning business. Kent received her first dose of the Moderna vaccine and had flu-like side effects that caused her to miss five days of work.

“I will not return for the second shot,” Kent said. “No one paid me, and I had to suffer with my bills, [so] I will just take my chances.”

Studies indicate that certain demographics are more likely to be hesitant to get a vaccine. In Sendero Health’s survey, respondents who were women, Hispanic and Latino or economically disadvantaged were all less likely to say they would choose to get a vaccine—although national vaccination data has shown women to be slightly more likely to get a shot than men. Black patients showed the greatest hesitation and were 47% more likely to say they would not get vaccinated.

According to Travis County Precinct 1 Commissioner Jeffrey Travillion, hesitancy among Black community members is tied to a lack of access to medical resources and infrastructure in the areas where many of them live. In Travis County’s eastern crescent, vaccine clinics were few and far between during the county’s initial vaccine rollout, he said.

“When you opened the first 74 places where you could get the vaccine, 65 of them were on the west side of I-35. It is not that segregation is a relic of an old generation; segregation and lack of access to equity is the reality today,” Travillion said.

In response, he said trusted community institutions have stepped up, including prominent churches such as Greater Mt. Zion Baptist Church and St. James Missionary Baptist Church, which both organized to hold clinics at their facilities.

Vanessa Fuentes, District 2 Austin City Council member, has similarly considered what factors will encourage her constituents to get vaccinated. Her Southeast Austin council district is 70% Latino—another population that has been disproportionately affected by the virus.

Much of the hesitancy Fuentes sees among Latinos is the result of misinformation, she said, which cannot always be fully corrected by doctors and health care providers since so many of her constituents lack health insurance.

Fuentes has pushed for a neighborhood-based approach to vaccine outreach, including pop-up clinics sponsored by organizations such as the Del Valle Community Coalition in East Travis County. She is also in favor of offering incentives to people who choose to get vaccinated. Incentive campaigns have been embraced in places including West Virginia, Ohio and Detroit, where vaccine seekers have been offered savings bonds, gift cards and even lottery tickets.

“Anything we can do to make it easier for folks and make folks want to get the vaccine is where our focus should be,” Fuentes said.

To reach people of color, vaccine-hesitant individuals or individuals who are of lower socio-economic levels, the Williamson County and Cities Health District operated a walk-up COVID-19 vaccination clinic in Taylor, said Deb Strahler, the county's marketing and community engagement director.

Strahler added in the coming months the WCCHD will be coordinating a vaccine hesitancy project, which will include community outreach and an advertising campaign.

“While demand is declining, we see a great need for continued health promotion and vaccination efforts to increase higher vaccination rates among our eligible population,” she said. “Without this continued push for vaccination by the [WCCHD] and our clinical partners, risk of variants which are not currently covered by approved [emergency use authorization] vaccines will continue to rise and may no longer be as protective as they are currently assessed to be.”

Building access

For some Central Texas residents, accessibility has proven the key to making a vaccine appointment. Austin Community College student Dulce Medina received her first dose April 30 at a vaccine clinic on ACC’s Highland Campus in North Central Austin—roughly a month after all adults became eligible. She was one of 800 ACC students, staff and family members to receive a Pfizer dose that day, along with her aunt, whom she brought with her.

“This is the first time [I’ve tried to get a dose] because my friends have had trouble finding other places that will give it to them,” Medina said.

Wright and her team have gone directly to businesses, reaching out to encourage them to allow residents time off to get vaccinated, a privilege not afforded to many essential workers.

“When you start feeling like you’re probably moving the needle because you’ve helped so many people, you just can’t help but want to do more of it,” Wright said.

Williamson County prioritized access and assistance early on in the vaccination distribution process, setting up several Vaccine Registration Technical Assistance Centers staffed by volunteers and county employees to help any resident or nonresident sign up for the vaccine. The centers helped residents sign up for the vaccine, but they closed May 1.

The county also helped organize three mass vaccination sites where hundreds of thousands of vaccines were distributed over the course of four months. Those sites closed in mid-May due to a lack of demand.

The National Guard also helped the county vaccinate homebound seniors, and Curative operated mobile vaccine vans in smaller communities.

“I’m proud of what our team did,” Williamson County Judge Bill Gravell said. “What I said was by Memorial Day we’ll have vaccinated every adult that would want to be vaccinated. That [goal] was certainly far exceeded.”

Ali Linan contributed to this report.