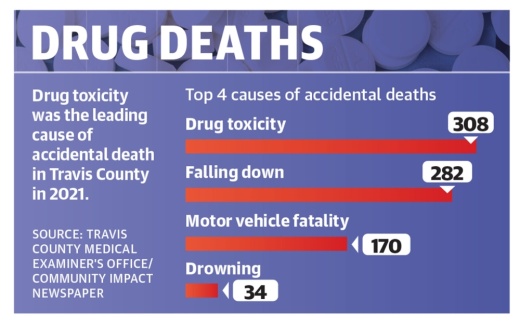

The purpose of the town hall was to urge local leaders to dedicate more resources toward combating drug overdoses, which the Travis County medical examiner would state in late May was the leading cause of accidental death in 2021 for the county.

“My question to policymakers is when is enough, enough?” said Nova Skye, outreach coordinator for the THRA, a nonprofit that focuses on health-based overdose prevention, asked at the May 3 town hall. “How many people need to die?”

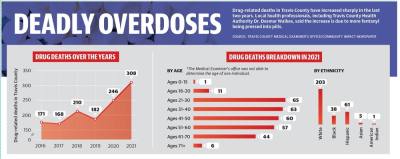

In 2021, 308 people died from drug overdoses in Travis County, according to the medical examiner’s report, an increase of 50 deaths from 2020.

Travis County Health Authority Dr. Desmar Walkes said a large contributor to the increase in deaths is a spike in fentanyl-laced pills on the street.

Fentanyl is an opioid 50-100 times stronger than morphine that was created to address pain in cancer patients, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. While it is still used for legitimate medical purposes when given by a licensed professional, it is also being sold on the street and mixed into other illicit substances.

The Travis County Medical Examiner’s Office found fentanyl in 118 of the county’s 2021 overdose cases, up 237% over the previous year.

At the town hall was Matt Hunt, a street outreach medic with CommUnity Care, which provides health care to individuals in encampments.

“When I started, what I saw was patients dealing with cancer, patients who were getting hit by cars, ... assault, rape and trauma—they were all surviving this,” he said. “Then fentanyl comes to town and my patients are dropping like flies. I am asking, we need to do something now.”

Austin EMS medic Mike Sassar said EMS does not track causes of death, but he said he is concerned about the pills being passed around.

“When a kid is getting [pills] from a kid in class or in youth group and goes home, no parent, no child will see a single pill and say this could kill me,” Sassar said at the town hall.

Addressing the epidemic

Travis County Commissioners Court declared drug deaths a public health emergency May 24.

“To put some perspective on it, there were 754 deaths in Travis County from COVID[-19]...” Travis County Judge Andy Brown said. “The medical examiner’s report shows that there were about 308 overdose deaths in Travis County.”

Along with the declaration, Travis County will provide $350,000 in funding to the THRA and other nonprofit organizations for staff, naloxone and hygiene kits; to hold monthly meetings with community members; and advocate for changes to state law, such as decriminalizing fentanyl test strips.

Bee Cave Recovery is an intensive outpatient treatment program for drug and alcohol addiction in Westlake. The eight-week program relies on a proven Twelve Step model and includes two-and-a-half hour meetings four nights a week in group and individual settings.

“This is an affliction that affects all classes and all socio-economic statuses across the board,” Executive Director Jim Anderson said. “We’re in Westlake, so we have a lot of very affluent clients, but also we’re a nonprofit. We provide treatment for those who are less fortunate and lower socio-economic status, and they’re all in the same group together.”

Anderson co-founded the nonprofit with Clinical Director Dennis McCarty, both recovered alcoholics with nearly 50 years of sobriety combined. Bee Cave Recovery receives a $500,000 grant covering the span of five years from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to cover treatment for up to 11 people at any time.

“I think we’re just on the tip of the iceberg in terms of [the drug epidemic]. It’s probably going to get a lot worse before it begins to get better,” Anderson said. “I’m glad that Travis County is taking sort of a proactive look at that, but... [$350,000] is not very much money. That’s a drop in the bucket, and that’s not going to spread that far. I think if they want to be really serious about [this], that [amount] should be a lot more.”

The nonprofit is currently seeking to increase their funds to meet growing needs, Anderson said. At a recent session, the organization accounted for 14 individuals, which is already over the budgeted amount, he said.

“When people need treatment, they need treatment. We’re maxing out in our funds for this year because we’re serving more people than we thought we would,” Anderson said.

Naloxone, often referred to by its brand name Narcan, is a nasal spray or injectable medication used to reverse an opioid overdose, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nonprofits and medical services provide naloxone. Many first responders also carry it.

Commissioners also authorized $50,000 to expand access to medication-assisted treatments May 10. These drugs, such as methadone, are used to manage addiction.

Dr. Jason Pickett, the chief medical deputy director for the city of Austin, said Austin-Travis County EMS is a key piece of the city’s response to addressing the crisis.

The department follows up with anyone who had an overdose and offers them connections to treatment programs, if requested, or supplies and education. If someone is interested in treatment, medics can all help the individual until a spot opens up.

“We can’t force people into treatment, but we can provide resources to those who do,” Pickett said.

A local crisis

In 2017, HHS declared the opioid epidemic a national health crisis. At that time, more than 10 million Americans were misusing prescription pills, one of the leading causes of the spike.

“We heard about the opioid crisis, and it was always in different states and even different counties until our county was one of the top five for the number of emergency department opioid-related visits,” Walkes said at a Commissioners Court meeting.

Travis County is party to several lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors.

According to the Travis County resolution, officials are hoping to offset the funding cost with settlements from one or more of these cases.

In February, Travis County signed onto a settlement with Perdue Pharmaceutical. The lawsuit alleges that the company “spread false and deceptive statements about the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use.” Travis County is also party to other ongoing lawsuits.

In 2021, West Lake Hills and Rollingwood also joined a nationwide multibillion-dollar legal settlement against Johnson & Johnson and three pharmaceutical distributors accused of wrongdoing amid the opioid epidemic. According to state documents, the settlement could allot West Lake Hills $17,056 and Rollingwood $4,754, though the total depends on how many municipalities sign on.

The THRA town hall was not just to bring visibility to the crisis, but to advocate for locally adopting a harm-reduction approach.

“It’s not as simple as saying, ‘Hey, here is some Narcan,’ but building relationships with some people,” Graziani said. “It could be meeting people, and they might say, ‘I need food or water. I need wound care.’ That’s how relationships are built; then you can have those educational conversations.”

The THRA’s work centers on public health-focused drug policy and low-barrier access to treatment. This includes providing supplies, such as clean needles, fentanyl test strips and naloxone, and drug education as well as addressing wraparound needs, such as hygiene and housing.

The THRA is advocating for officials to treat overdoses as a health issue, rather than focusing on law enforcement.

Graziani said research shows the “war on drugs” method of strict enforcement and tough sentencing is not effective and has disproportionately targeted communities of color and low-income individuals.

Though there is a healthy amount of collaboration among recovery communities within Austin, Anderson with Bee Cave Recovery said there needs to be more coordination on the county level to seriously treat this matter.

“I think there needs to be more outreach to providers, and I think there needs to be more opportunities for collaboration–more communication at the community grassroots level, because we’re the ones on the frontlines treating these people,” Anderson said.

The Austin Police Department declined requests for interviews for this story.

The Travis County Sheriff’s Office is working to expand education around fentanyl, said Kristen Dark, spokesperson for the Travis County Sheriff’s Office. She said the county is providing information about health risks and the prevalence of the drug to individuals in Travis County’s jail, and she is also in talks with local districts.

Cristina Nguyen with Austin ISD said the district counselors meet with students to conduct wellness checks and provide information to families around drug awareness.

“As someone who has been working on this for many, many years, [the emergency declaration] is kind of a historic win because this is the first time the county has shown real support for harm reduction,” Graziani said.