“There’s a lot of small local businesses that are struggling right now. And especially [for] restaurants and small food businesses and other bakeries—the cost of goods has gone up so dramatically,” said Karen Fry, who has owned Dream Bakery since 2016.

The restrictions on businesses from the height of the pandemic are over, but local restaurants in Northwest Austin are still riding out the storm. The number of people patronizing the food service industry is back on the rise with more people dining out and ordering food delivery or takeout, but business is still not back to pre-pandemic levels, according to OpenTable data, which compared data from 2020 22 with pre-pandemic data from 2019.

In spite of the increase, 83% of Texas restaurant operators recently reported that their restaurant is less profitable now than it was in 2019 before the pandemic, said Kelsey Erickson Streufert, chief public affairs offi cer for the Texas Restaurant Association. This is due to price increases across the board on everything from food to labor to overhead, according to the National Restaurant Association’s national survey of 4,200 restaurant operators conducted between July 14 and Aug. 5.

Local restaurant owners said they are trying to cope as much as they can, but some city and state wide factors are out of their control.

“The supply chain disruptions, inflation, lack of workers—not just in restaurants but really all up and down the supply chain—have created some real sharp price increases,” Erickson Streufert said. “Same pressures are also impacting our customers and their ability to dine out and creating a really tough economic environment for many of our restaurants.”

Rising costs

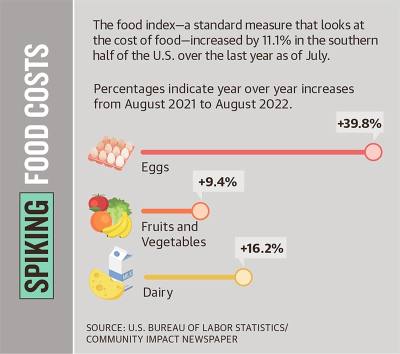

Local restaurant owners said the rising cost of ingredients affects their bottom line firsthand by reducing the buffer between the cost of doing business and the price on the menu. The consumer price index, which looks at the rising cost of food, shows the price of food went up 11.4% between August 2021-August 2022. The price of sugar rose 16.7% in that time period. Over the past year, wholesale food prices increased more than 17%—the largest increase in nearly 50 years.

Adam Li is the owner of House of Three Gorges, a local Chinese Szechuan cuisine restaurant near Burnet Road and US 183.

“[The price of] ingredients, supplies, everything, oil, rice, vegetables went up, and the price increased significantly. Not by a few dollars but in some cases doubled. It is a big deal,” Li said.

Li also faces sta ng issues. His second Szechuan chef left one month ago, and he has still not found a replacement, he said. “Someone offers a higher salary to your staff and they’ll be gone the next day,” Li said.

It is a competitive business, and recruiters from even out of state make offers, he said.

Li said he copes with rising costs by working long hours, multitasking and reducing his profit. He began closing the restaurant between 2:30-4:30 p.m. so his staff can rest. He said he is also trying to reduce dependency on DoorDash and Uber for delivery services, which charge a high price to businesses for offering the service.

Located in the Shops at Arbor Walk off MoPac, Masala Wok is a local family-owned restaurant that has been serving Asian and Indian cuisine since 2003. The restaurant faces

the same supply chain issues and rising cost of ingredients. To cope with shortages in staff, owner Sanjay Parikh placed ads online and spread the word through his local network but has seen little response.

“[Those that apply] say, ‘OK, we’ll be there tomorrow at this time,’ but nobody shows up,” Parikh said.

During the pandemic, businesses with historical payroll data could apply for a paycheck protection program or receive an Economic Injury Disaster Loan. While The House of Three Gorges did not have this data because it opened during the pandemic, Masala Wok did receive federal help, but business was so poor the loan forgiveness only went a short way, Parikh said.

Masala Wok had no choice but to increase its prices by 10%, Parikh said.

Aside from local dine-in restaurants, niche fast-food restaurants such as P. Terry’s Burger Stand also felt the rise in prices. The chain additionally faced the dilemma of having an established customer base that is used to the burger joint’s staple menu, P. Terry’s CEO Todd Coerver said.

Restaurateurs are themselves looking for the perfect price to set on the menu, a range that lies between the total cost of running the business and the price the customer is willing to pay, Coerver said.

“We always look at what our competition is doing; it’s a very delicate dance,” Coerver said.

Aida Tabakovic, who owns Poke House north of Braker Lane with her brother Edin, said the price of the main ingredient—fish—has doubled since the pandemic.

“I always put myself in the customer’s shoes, or I’m pretty frugal, myself. I don’t like having to spend a lot of money, and I would love for more customers to be able to try our food,” Tabakovic said.

Shortage of wage workers

Heather Smith is the general manager of The Boat at the intersection of MoPac and Braker Lane. In addition to her usual workload she does payroll, buses tables, onboards new employees, handles human resources requests and provides assistance to short staffed areas.

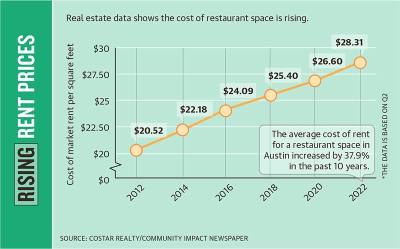

Combined with rising rent, increased gas prices and rising population, Austin is getting more expensive, and hourly employees are no longer able to live in the city, leaving many jobs in the restaurant industry unfilled, Smith said.

“Even if you are lean and effi cient, are reducing your hours or streamlining your menu or [using] other techniques to try to just be more effi cient, you still have to have a certain number of people to be able to open your doors,” said Erickson Streufert of the Texas Restaurant Association.

Operators who are throwing in the towel right now are just not able to keep up with that grueling workload, Erickson Streufert said. TRA data showed 67% of Texas restaurant operators reported they do not have enough employees to support their existing customer demand.

Under current circumstances, Li said he can hold up for a year. His food is a niche market in an area where by word of mouth he has developed a loyal customer base. But he said he worries about his customers, too.

“When people are not sure if their jobs are stable, or if investment in the stock market is going to hold the value, they kind of hesitate to spend the money on dining out,” Li said.