A shortage in foster homes and available beds at emergency shelters has contributed to ongoing difficulties faced by officials in providing services to children in the foster care system.

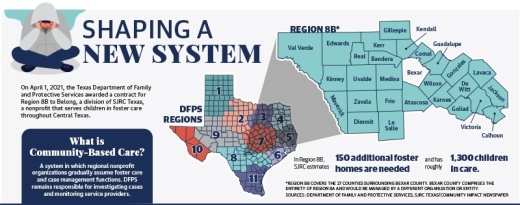

As the state grapples with finding safe placements for children in the foster care system, an initiative that will shift placement and case management from the DFPS to local organizations is underway in Central Texas.

The state’s Community-Based Care initiative prioritizes local placements and prevention services in an effort to ensure children can access their home communities and service providers.

In spring 2021 SJRC Texas, which previously operated as Saint Jude’s Ranch for Children, formed its Belong division to implement CBC in the region that includes Comal County.

Megan VanDusen and her husband, who live in Comal County, began fostering children 12 years ago and have since adopted three children they previously fostered. While two of her children were from a nearby county before entering foster care, her daughter’s biological family was not as easily accessible when she was placed with the VanDusens. Because her daughter’s Child Protective Services caseworker was too far away to make regular visits, VanDusen said another CPS worker was assigned to make monthly visits to ensure her daughter’s needs were being met.

“She was more local, so she could kind of help us navigate that a little bit differently, but also again, our [adoption] agency is who we depended on more for kind of like the daily ins and outs,” VanDusen said. “We’ve kind of had it a lot of different ways. Some are able to help more than others. But there’s just a lot of teamwork and sending out information asking for help and trying to navigate that all together.”

As the region shifts to a more localized model of services for foster families, local organizations, and foster and adoption agencies are hopeful that the system will simplify the process for children to receive the care they need.

Community-based care

In 2010, the DFPS began the Foster Care Redesign effort that expanded the role of community service providers to include placement services, network development, community engagement and the delivery of services to children in foster care through a Single Source Continuum Contractor, or SSCC.

An SSCC is an existing organization or nonprofit that is located in one of the 11 DFPS regions and contracts with the state to offer services for foster children within that region.

The state’s redesign project was expanded in 2017 when the Community-Based Care model was established to further transition the state’s child welfare system from a statewide approach to regional service providers. “It’s a sweeping system change from the state handling all of the foster care and the placement and everything to a contractor such as a nonprofit organization,” said Lauren Sides, chief public relations officer for SJRC Texas, which previously operated as Saint Jude’s Ranch for Children.

In the spring of 2021, SJRC Texas received a contract to oversee the initiative for DFPS Region 8B.

Region 8B spans 27 counties between Jackson County and Val Verde County, though Bexar County is separated into Region 8a.

Community-Based Care is broken into three stages, during which the contractors work with state officials to create a local network of services, foster homes and other living arrangements before assuming case management responsibilities.

SJRC Texas formed the Belong division to act as an SSCC and began managing foster care placements in October, Sides said, which is the first stage of implementation.

In late 2018, The Children’s Shelter in San Antonio received a contract to serve Region 8A and formed Family Tapestry to act as the contractor, according to DFPS documents. Family Tapestry began accepting placement referrals in early 2019, but gave notice to terminate its contract in April 2021 after closing its emergency shelter. The DFPS resumed all responsibilities by July 2021.

Jacob Huereca, CEO of Connections Individual and Family Services in New Braunfels, said although Family Tapestry failed, area shelters and agencies gained experience with the system and were prepared to work with Belong. CIFS operates a youth shelter that is partnered with Belong to provide emergency placement services.

“Because Family Tapestry had already started privatization of San Antonio, all the providers in this area were used to how to set up a separate contract,” Huereca said.Through the new system, the DFPS will notify Belong before a child is removed from their home within Region 8B and staff will begin searching for an appropriate placement with a local provider or foster home, SJRC Texas CEO Tara Roussett said. “We send out a mass blast email to all of the providers to see if they’re able to take them, and we work nonstop until we can find placement,” Sides said.

A primary goal of the CBC program is to keep children as close to their home community, school and support system as possible, she said, and contractors are encouraged to place children within 50 miles of their home, if possible.

“In the prior system, sometimes kids, let’s say, were from New Braunfels—they could be placed in Dallas,” Sides said. “And that can be equally as traumatic [as being removed from their home], going from a smaller kind of community to this big city and not knowing anyone.”

If a placement is not found, the SSCC becomes the direct provider of care. In regions without a contractor, the DFPS becomes the provider.

Children without placement

Across the state, the number of children who spent at least one night without proper placement skyrocketed from 53 in September 2019 to 416 in July 2021.

Multiple factors have contributed to the rise in children without placement, or CWOP, including hundreds of beds lost due to facility closures, according to a September report by court-appointed monitors inspecting Texas’ foster system.

In 2018, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals established “heightened monitoring” of Texas’ child welfare operations as a result of ongoing litigation against the state.

As a result of the court’s order, Texas lost 2,129 general residential beds between January 2020 and September 2021, according to the report.

In 2021, Senate Bill 1896 forbade DFPS and SSCCs from housing children in an office overnight.

“That didn’t do anything because what they did is instead of putting the kids in offices, they started putting them in hotel rooms or churches,” Huereca said. “These are still kids without placement. They just weren’t in the office building.”

The DFPS has identified a need for 669 additional beds throughout the state, according to the report, and Belong estimates 150 foster homes are needed in Region 8B.As of January, Sides said there were no children in the region that were without placement.

At the emergency shelter in New Braunfels, Huereca said the shortage of foster homes has led to longer stays for children and youth with the average stay ranging from 50-60 days.

“We have seen with COVID[-19], especially with our older kids, they are staying a lot longer, unfortunately. ... A lot of times because there’s nowhere for them to go,” he said. “You really don’t want the kids to stay at the shelter too long because that’s what it is—it is supposed to be an emergency shelter to house kids. You don’t want kids growing up in a shelter. We want kids to be raised by families.”

Teenagers at risk of being left behind

Older youth in the foster system tend to experience longer stays without placement, according to the DFPS September report. From October 2020 through September 2021, 32.11% of children ages 13-17 were without placement for three to seven nights, while 15.69% of children ages 3-5 were without placement for the same duration.

A total of 211 children ages 13-17 were without placement for more than 28 days over the course of the fiscal year, according to the DFPS. “A lot of people want to become foster parents and help the little kids but our teenagers, unfortunately, kind of get left behind in that,” Huereca said. “Our kids that come into the foster care system, they do come with baggage, but it’s not baggage of their own. These kids have been through hell and back. And they need people who are willing to be skillful to help them heal.”While families receive training for caring for children with trauma, organizations such as the South Texas Alliance for Orphans have worked to empower communities and churches to support foster families.

“We also do trauma training for foster families, adoptive families, kinship families ... anybody else that is kind of connected with those that have experienced trauma, helping give them the resources and tools to know how to serve them,” STAO Director and founder Jennifer Smith said.

Children over the age of 9 are often less likely to be adopted if parental rights are terminated, Smith said, which leads to longer stays in foster care and a higher chance of experiencing negative outcomes without a consistent family dynamic. Community support is critical

Keeping children connected to their biological families is also a key priority of the CBC initiative, Roussett said, and the DFPS prioritizes kinship placements or placements with safe adults the child is familiar with.

“[Children’s] best outcomes are staying close to home with people that they know, and that’s going to take the community stepping up,” Roussett said. “There’s some good people that are working very hard to do the right thing for these kids. But we need more, no one entity can do it alone. No one agency can do it alone. It truly takes the community.”

For those who may not be in a place to become a foster family, Smith said opportunities to serve foster families and children are abundant in the community. STAO hosts a babysitting program to license people to babysit foster children and partners with area organizations to provide school supplies and Christmas gifts for foster families.

Court Appointed Special Advocates trains volunteers to serve as a guardian ad litem, or a legal guardian appointed by a court, and are responsible for speaking with the child’s teachers, therapists, doctors and the child to determine whether their needs are being met.

“There are a lot of things that these children need while they’re in care, and CASA volunteers find out these needs and make them known to the judge so that then court orders can be put into place,” said Eloise Hudson, communications manager for CASA of Central Texas. In an effort to provide consistency for the children in care, each CASA volunteer is only assigned to one case at a time, Hudson said.

As the population in Central Texas has grown, so has the number of children in need, Hudson said, outpacing the number of volunteers available.

While some foster placements end in adoption, like VanDusen experienced, she said foster families should never hope a biological family breaks down and should instead focus on providing the care and healing a child needs while they are with them.

“A lot of times we look at either these kids or their parents with judgment. And I think if we just look at them as broken people like we all are, we’d have a little bit more compassion. We’d have a little bit more grace because it is so cyclical, and someone has to be willing to step in to help break the cycle,” she said. “The healing process is so important that they need people that are willing to sacrifice their temporary comfort for their permanent well being.”

Chandler France contributed to this report.