The city of Georgetown has spent $10.63 million purchasing land through the authority of eminent domain since 2016, according to city records.

As a result, the city has acquired about 12 acres of land to complete six road and wastewater projects, city officials said. In doing so, the city is focused on building and extending infrastructure for public benefit, said Travis Baird, city of Georgetown real estate service manager.

One of the most recent city projects being completed through the use of eminent domain is the Northwest Boulevard bridge project, an I-35 east-west overpass bridge that connects north of Rivery Boulevard with FM 971. This project is expected to be completed in late 2021.

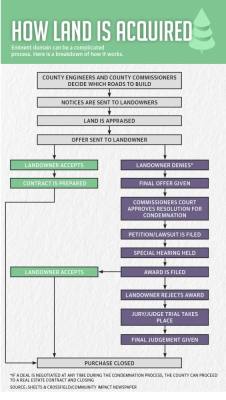

Eminent domain use is when a government entity, such as a city or county, takes private property for a public purpose such as roads or pipelines. The terms eminent domain and condemnation can be used interchangeably, Dan Gattis, a Georgetown eminent domain lawyer said, but eminent domain is the power while condemnation is the process. Public purposes do not include economic development, and “adequate compensation” must be given to the landowner, according to the Texas Constitution.

Landowners in many condemnation cases, he said, settle or take the first offer because they are “scared to death of getting sued” or to push the entity into a lawsuit.

Gattis, a former state legislator, said eminent domain legislation reform is needed to create standard, minimum terms to help landowners who do not seek law counsel and to ease disparities in land value. Though some entities treat landowners fairly, he said there is a significant advantage in seeking counsel to affirm property rights and fair value.

“I think they would be better off in the end if they at least get some counsel or get some advice through the process,” Gattis said.

Baird, who is responsible for the legal side of condemnation on behalf of the city, said the process to acquire land involves the city entering into negotiation with the property owner; if this fails then the city—by way of City Council—authorizes condemnation.

He said that condemnations can only take place if there is a public purpose for the property. He added that not all land acquisitions result in lawsuits; in fact, formal legal procedures only begin when the city and the landowner cannot agree on a price.

“The government has the ability to take your property from you and put it to that public use,” Baird said. “If the city seeks to condemn property and there’s justified public need, then it comes down to value.”

Gattis said it is the fear of a lawsuit that leads many property owners to settle cases or take the first offer.

“The power of eminent domain and the condemnation process is like a gun to the property owners’ head,” he said. “You’re going to lose the property; you better start negotiating on price.”

Eminent domain in Georgetown

Since May 2016 the city has filed 11 petitions to condemn property, according to city records.

For the city to file the petition to condemn, the city would have to have entered into negotiations with the landowner where an agreement was not reached, then the city by way of City Council authorizes condemnation in a public act, Baird said. Most city condemnations are for roads and wastewater lines, he added.

The use of eminent domain by the city resulted in six projects within city limits, including the Rivery Boulevard extension, the Northwestern Boulevard bridge project, the FM 971 realignment, the Cowan Creek wastewater interceptor, the Mays Street extension and the Rabbit Hill Road expansion.

Eminent domain is more often used in rural areas because urban or neighborhood land is more costly than ranch land. Nonetheless, Gattis said people are becoming more aware of eminent domain because it is used so much in the Williamson County area.

“The city of Georgetown has a responsibility to provide efficient and affordable services to our residents and rate payers. Being able to build infrastructure and provide quality services, while balancing the needs and maintaining the trust of all stakeholders, is a critical component of that responsibility,” Mayor Josh Schroeder said. “The condemnation process ensures the city can fulfill our obligations and that the landowners’ rights are protected.”

Each project established is intended to help better infrastructure in Georgetown, Baird said.

“[Eminent domain] is not something we take lightly,” Baird said. “At the end of the day this is their city; we are their staff; and we want to make sure we communicate to them.”

No property owners impacted by eminent domain use by the city were willing to speak on the matter.

On behalf of the county

Gattis said he has seen Williamson County often use eminent domain to plan for future growth rather than take land for a current need. Lawyers for government entities argue that purchasing land in advance to “land bank” saves taxpayers money, he said, but he does not believe that is the purpose of eminent domain.

“The [Texas] Constitution says it needs to be for a public purpose and that purpose only,” Gattis said. “It can’t be for a public purpose for 20 years from now.”

Lisa Dworaczyk is the right of way coordinator for Sheets & Crossfield, which represents Williamson County and other area cities in eminent domain disputes. She said while some entities do take early acquisition—or the purchasing of land before current need—into consideration when land is up for sale, it ultimately comes down to price and whether the entity can afford the cost of an extra project it was not scheduled to take on. However, if early acquisitions do take place, they are in line with the county’s long-range transportation plan, she said.

Williamson County as an entity is also using eminent domain to build roads, with members of the Commissioners Court regularly stating that in doing so they are trying to avoid the future traffic problems that can be seen in Austin.

“To be a successful community, there are several things that matter—safety’s important; good schools are important; quality of life for employees is important and what I would call transportability, or getting from point A to point B,” Williamson County Judge Bill Gravell said. “[Transportation] is the one area that I think the county has been very forward-leaning on and really well prepared.”

Since 2016, the county has acquired 512 parcels of land for 33 different road projects. Those projects include a project on D.B. Wood Road and CR 111 and along Westinghouse Road, among others, according to county data.

Of the 512 parcels, there were 43 resolutions for condemnation, or the threat of a lawsuit, with 28 filed lawsuits. However, 15 saw a court proceeding, Dworaczyk said.

She added that lawsuits stop as soon as an agreement is made, but there is little room to negotiate the price.

“I would say the majority of our negotiated tracts will come within 20% or so of what we appraised it at,” Dworaczyk said. “I can’t just give [money] to you because you’re asking for it. We have to be responsible stewards of the taxpayer dollar.”