It is 105, according to a 2019 Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce report.

This net migration is one of many challenges facing census workers and organizers.

Where will the approximately 105 people moving on Census Day—April 1—count themselves residents? Will it be where funding is needed for the congested roads they drive on, the under-enrolled schools they may send their kids to and the flood-prone neighborhoods in which they put down roots?

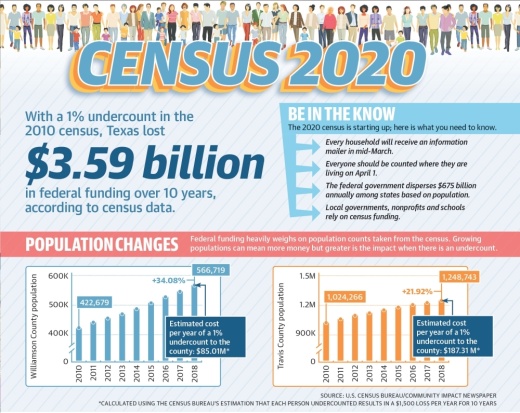

For each person uncounted during the decennial census a community loses $1,500 in federal funding each year for the next 10 years, Julie Wheeler, Travis County Intergovernmental Relations Officer told county commissioners in January.

Federal funding for myriad programs—such as natural disaster relief, Medicaid, student loans, housing vouchers, highway construction and subsidized lunches—is connected to census numbers, census official said.

“Texas only looks like it is going to grow, so if we came with an undercount in 2020, we’d immediately face less money coming back into Texas,” said Douglas Loveday, senior media specialist for the U.S. Census Bureau.

If those 105 brand-new residents are uncounted, the metro stands to lose $1.58 million between 2020 and 2030, when the next census is taken, census data shows.

And they are only one of the many groups at risk of being undercounted.

Reaching the hard-to-count

Children age 5 and younger, college students, people of color, immigrants living here without legal permission, people experiencing homelessness, the LGBTQ community and people who do not speak English are all considered hard to count by the bureau.

These populations present different challenges. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, their members may be hard to interview due to language barriers, illiteracy or lack of internet access; hard to locate; hard to contact because they are highly mobile or are experiencing homelessness; and hard to persuade because of fears or a low level of civic engagement.

“We have an idea of where these harder-to-count folks are, but we don’t know who they are,” said John Lawler, Austin-Travis County Census Program manager. “They are not engaged with institutional channels. And so it’s a much more difficult process [to reach them].”

For some hard-to-count communities, the census is an unfamiliar concept.

According to a 2019 Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, Asian Americans are the fastest-growing major racial or ethnic group in the country.

Marina Ong Bhargava, CEO of the Greater Austin Asian Chamber of Commerce and a member of the Austin-Travis County Complete Count Committee, said some Asian immigrants may come from countries where the government is corrupt or untrustworthy.

“We want to make people feel comfortable about answering questions,” Bhargava said.

She pointed to the local Nepali community, which has been educating members about the race and ethnicity question on the census questionnaire.

“They were actually very interested in being counted as Nepali,” Bhargava said. “So they were teaching each other that you need to check the ‘Other’ box, not the ‘Asian’ box, and then write in ‘Nepali.’ That way, the census will have a different category for them.”

In addition to complete count committees, other local organizations have thrown their support behind the census effort.

Design Jam, a local graphic designer meetup, is participating in Creatives for the Count, a national effort to increase census participation.

In February, the group convened local graphic designers to create posters, memes and other messaging to encourage participation.

“We can design Facebook pages until the cows come home, but that’s not necessarily going to reach someone who’s a freshman at UT,” said Jennifer Houlihan, Design Jam organizer. “We have to be willing to meet them on TikTok with a short video.”

Per the National Conference of State Legislatures, Texas is one of three states—along with Nebraska and South Dakota—to have taken no action to support the 2020 census effort, leaving city and county governments the task of ensuring a complete count.

State Rep. Cesar Blanco, D-El Paso, authored a bill during the last legislative session that, if passed would have allocated $50 million to ensuring a complete count.

“There is a concern that an undercount may benefit Republicans,” Blanco said, when asked why he thought his bill lacked bipartisan support.

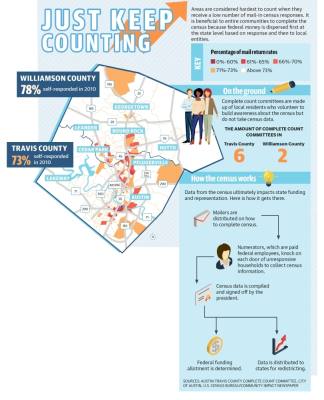

Both Travis and Williamson counties have convened local complete count committees—with members hailing from faith organizations, local nonprofits and other community groups—to raise funds and develop outreach strategies and priorities.

The city of Austin and Travis County each committed $200,000 to this effort, in addition to $195,000 in additional funds. Williamson County’s complete count committee and its local health district received $35,000 in grant funding to support outreach to hard-to-count communities.

“Now we’re actually trying to put most of our time and energy into ... getting these community groups to tell us where to spend the money we’ve got and connect us with their own volunteer networks because folks are more likely to answer the door if it’s someone from their community,” Lawler said.

Georgetown City Council Member Mary Calixtro echoed this.

“It has to be done by people they trust,” she said of census outreach.

The Austin-Travis County Complete Count Committee includes a representative from Austin ISD.

More than 70% of the district’s 80,900 students are from minority racial or ethnic groups; more than half are economically disadvantaged; and nearly a third are English learners. Sixty-two of its 129 schools are part of the federal Title I program, which provides funding to schools with a large concentration of low-income students.

Earlier this year, the district led a series of staff trainings—with a focus on parent support specialists, who work in Title I schools—to serve as census ambassadors.

“Legally, our [parent support specialists] cannot help people complete the census because they’re not government employees. But what we can do is create the spaces for those individuals to help our families come in,” said Leonor Vargas, administrative supervisor of AISD’s parent engagement support office.

Acknowledging concerns

There are 10 questions included on the census questionnaire.

None of the questions ask about citizenship status, despite an effort by the Trump administration to add one in 2018.

Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such a question was unconstitutional. But the proposal has had lingering effects.

In a study published by the U.S. Census Bureau last year, nearly half of participants reported concerns about data privacy and confidentiality that might prevent them from completing the census questionnaire.

“[R]acial and ethnic minorities were significantly more concerned about confidentiality than [non-Hispanic] whites,” the study found.

The Austin-Round Rock metro is home to around 100,000 immigrants living in the country illegally, per a 2019 report by the Pew Research Center.

“There is an absolutely legitimate reason for folks to feel like they’re being targeted because they are,” Lawler said. “Our job is not to try to argue against their own concerns [but] to try to inform them about what the consequences are in a world where they aren’t counted.”

Genesis Sanchez is the regional census campaign manager for the NALEO Educational Fund, which facilitates civic engagement among Latinos. The region she oversees is the state of Texas.

“What we’re hearing from groups on the ground is there’s a lack of trust in the government right now,” Sanchez said. “They’re conflating the administration with the [census] bureau.”

To address these concerns, Sanchez encourages volunteers and other organizers to anticipate questions people may have about the census, such as whether their responses will be shared with their landlord or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, but that information will not be shared, officials said.

“It’s almost like you’re saying the quiet part out loud,” she said. “It helps facilitate trust.”

Census organizers also said it can be helpful to explain how the data is used.

“There should not be fear in filling out the census regardless of immigration status,” said Marissa Austin, chair of the Williamson County Complete Count Committee and CEO of CASA of Williamson County, a network of court-appointed special advocates who work with children in protective custody. “The information is protected by law. It cannot be shared. It is strictly used by the federal government for the census count.”

It is also worth noting what is not on the census.

“If you do get a form about your citizenship status or any banking information or your full social security number, do know that is not the official census form,” said Katie Martin Lightfoot, census community engagement coordinator for the Center for Public Policy Priorities, an Austin-based think tank. “That is a scam. Please do not fill it out.”

Laying the groundwork

Local elected officials, complete count committee members and organizers stressed the benefits of participating in the census, which they consider not only a legal requirement but also a right.

“It doesn’t matter if you are documented, undocumented, a citizen, a non-citizen,” Martin Lightfoot said. “You get to fill out the census form because you are a part of the community, and you deserve to be counted.”

Not being counted disadvantages individuals as well as the communities to which they belong.

Take, for example, young children, beneficiaries of federal programs whose funding is tied to census data, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC; Head Start; and Title I.

“If we miss one of these kids when they’re, say, 3 to 5 years old, we miss them for almost their entire K-12 education,” Lawler said. “Those kids will still need [subsidized] lunch dollars. And so it is not only a missed funding opportunity, but it’s also an increased local tax burden.”

A child who is 4 years old today will be a 14-year-old high schooler in 2030, when the next census occurs.

The gap between counts can make fundraising and organizing difficult. But where some may see a challenge, Sanchez sees an opportunity.

“We want to frame this as a really positive experience,” she said. “This is a long-term game. There will be another decennial.”