As a single working parent she said she understands the hardships that come with raising children while also working multiple jobs to keep food on the table and a roof over their heads—a hardship that has intensified with the coronavirus pandemic.

Georgetown ISD, along with partners such as the Boys & Girls Club, has worked to minimize the pandemic’s impact on education, particularly for children who are economically disadvantaged.

While typically serving as the teen coordinator for the club, Mireles switched roles to run the COVID-19 remote learning program after the district announced in July that it planned to start the school year with three weeks of virtual learning before offering optional in-person classes on Sept. 10.

The club cared for 45 economically disadvantaged students ages 6-12 from Aug. 20-Sept. 9, allowing the students to gain internet access and receive help logging into virtual classrooms under adult supervision, all of which they would not have otherwise.

“Some parents are working two jobs or have to work at night, [and] some kids don’t have an older [sibling] who can help them log in. So their education is one of the first foundations that we put into motion when we did the three-week virtual camp,” Mireles said.

The coronavirus has impacted and continues to impact the education of students since Central Texas schools began to close in March, but students who live in an economically disadvantaged home are even more harshly impacted.

A Texas Education Agency June report found that as many as 12.45% of Texas’ socio-economically disadvantaged students either lost engagement or contact with teachers during the end of the spring semester. Lack of internet access, technology access, and/or adult supervision and help were all factors, experts say.

The same report found that younger students from early education through first grade also had higher rates of lost engagement or no contact, likely due to the need for parent or guardian aid with technology.

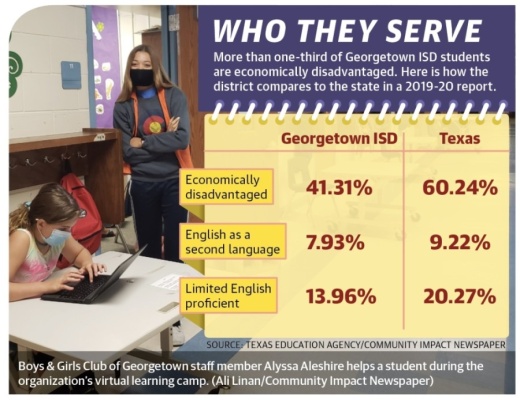

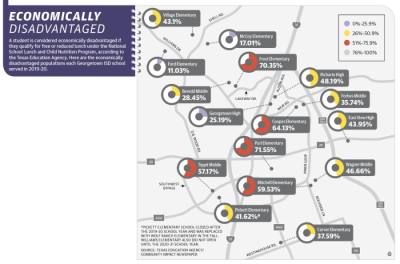

TEA defines economically disadvantaged students as those who qualify for free or reduced lunch under the National School Lunch and Child Nutrition Program. Of GISD’s 12,163 students, 41.31% are deemed economically disadvantaged, according to TEA’s 2019-20 school year reports.

In the spring, Georgetown ISD lost contact or engagement with 14% of its students, according to the district’s data. Of the 5,280 economically disadvantaged students, 23% of students lost contact or engagement with the district, data shows.

The district was already aware of and working on initiatives to improve equity and provide each student with his or her own tablet or laptop prior to the pandemic, said Cynthia Pike, GISD director of college, career and military readiness. But COVID-19 highlighted the district’s needs, pushing up timelines for programs and forcing plans to become actualized, she said.

“COVID-19 absolutely ripples inequities to every person everywhere in every organization,” Pike said. “All of us [at GISD] have learned more about the inequities that live within our systems.”

And while COVID-19 did show disparities between different groups of people across multiple avenues, GISD Director of Communications Melinda Brasher said the pandemic also emphasized the need for public education in removing barriers within a community.

Brasher said public school systems act as a conduit connecting families to resources in health care, mental health and basic needs such as clothing and food, all of which was made more evident with the pandemic.

“I think public education in so many ways proved to be such a critically essential component to our system in America for how we serve not just students in learning but their families across the board,” Brasher said. “When kids are in schools, we’re not just serving kids, we’re serving their families.”

Community partners

The Boys & Girls Club of Georgetown, which offers programming geared toward economically disadvantaged kids, knew it had to step in and offer a remote learning option for families who rely heavily on the school system, BGC Branch Director Kelly St. Julien said.

St. Julien said the organization, which provides after-school care regularly to 150 kids, will only accommodate 90 kids beginning Sept. 10 in order to maintain social distancing rules. But keeping the club open, even in limited capacity, allowed for more kids to be cared for than would have otherwise.

He added that he believed families with financial security were more easily able to adapt to quarantine and remote learning, but the families the Boys & Girls Club serves often could not.

“Our parents have very limited windows of time where they can even interact with their kids because they have tremendous pressure to be at work constantly. And they’re in the types of jobs that they don’t accrue vacation [or] accrue time off. They work or they don’t get paid,” he said.

The sentiment on an organization’s need to adapt to stay open and provide services for this group of kids was echoed by Leslie Janca, CEO of The Georgetown Project, an organization that works to help kids connect to needed resources and develop positive relationships to ensure a better future, according to its website. Janca said 90% of the about 2,000 students it serves are low-income, and 80% of those served identified as racial minorities.

A large part of the Georgetown Project’s work is to aid at-risk youth with education and mental health needs. Janca said she did see the impact the pandemic had on many of the kids served, either by affecting their family life or minimizing their interactions with positive role models.

“What we tried to do was stay connected with our kids and their families during that time and mobilize in whatever way that they needed,” Janca said.

The First Baptist Church Georgetown also hosted 90 kids from Aug. 20-Sept. 9 and provided child care, educational assistance and meals.

Access to food and food security can play a large role in the educational success of a student and also disproportionately impacts economically disadvantaged students, experts say.

GISD did offer meals for students and families in the spring and summer as well as made concerted efforts through snack-providing programs to provide warm meals to kids who needed them but did not have access to transportation. But under the Texas Department of Agriculture rules, beginning in the fall parents had to pick up the free or reduced-priced meals for their child while providing a valid school ID, which could be another barrier for working parents, First Baptist pastor Brett Levy said.

This is why he said providing breakfast and lunch for the kids at his camp, as well as 50 others at the YMCA’s GISD remote learning camp, was important to his church, as many of the kids it cared for qualified for free and reduced lunch.

Levy said it was no question for the church to offer such a program for the community’s most vulnerable children. He added that in the intake form filled out by each child’s parent, he found many kids at the camp did not participate in school instruction after schools closed in March.

“We just know that in our community, we have some kids that educationally have a harder time more than probably the normal amount, because of socio-economic disadvantages,” Levy said. “If a single parent has to work full time, then that makes it difficult to lean in and help in the education process. If [the kids] didn’t have this, they would be sitting at home, and they would be three weeks behind when school started.”

Demographically different

The city of Georgetown possesses a relatively well-educated community with a low poverty rate of 7%, compared to the state rate of 14.9%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But that is not necessarily the case for Georgetown ISD, whose boundary lines expand beyond the city’s more than three times over.

And while the city is composed of 90% white people, the district’s population is made up of 45.72% white students, with 43.54% of students identifying as Hispanic or Latino versus the 21% of city residents who do so.

GISD CCMR Director Cynthia Pike said through the district’s initiative to improve equity, it also recognizes the changing demographics of its student body and is working out ways in which it can be culturally responsive through every aspect of the education it provides.

“If we want to empower, inspire every learner to lead, grow and serve, then our focus has to be on every single learner,” Pike said. “We have to make sure that we’re intentional about how our population is changing.”