The financial impact of the coronavirus continues to shake economies and budgets around the world and in every industry, including education and that of Georgetown ISD, which is in its final stretch of solidifying a fiscal year 2020-21 budget.

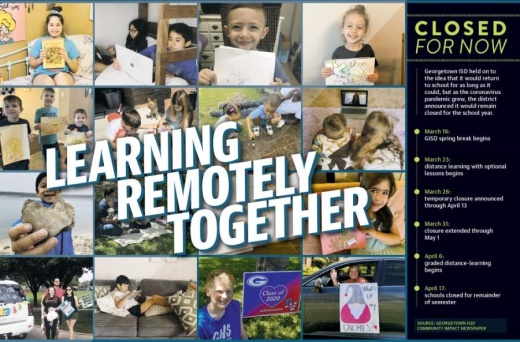

GISD, like all area schools, did not return from spring break. Instead, campuses closed, and teachers, parents and students were tasked with distance learning.

After holding out for weeks on the idea that it could still reopen before year’s end, GISD announced April 17 it would remain closed for the semester, following an announcement by Gov. Greg Abbott to do so.

Since then, the district has faced several unforeseen expenses due to the pandemic, including technology purchases and meal distribution, which have impacted its budget. A new budget for FY 2020-21 must be adopted before July 1.

“We’re kind of slow playing, what the impact [of the coronavirus] will be,” GISD Chief Financial Officer Pam Sanchez said. “We are hoping to be conservative and hoping to adopt a balanced budget like we do each year.”

GISD spent about $283,000 in coronavirus-related expenses during March, officials said.

Since its closure, GISD has lent out 3,000 laptops and 450 Wi-Fi hot spots so students can complete assignments online.

In addition to technology, this includes the printing of learning packets for students, software licenses for remote access tools, the licensing to support remote phone service, additional sanitizing and disinfecting supplies, the installing of a hand sanitizer station in every classroom, general office supplies to support device distribution, and protective equipment for staff distributing meals and devices, officials said.

“Thanks to voter-approved funds from the 2015 and 2018 bonds, Georgetown ISD has been investing in technology for years, putting us in a good position to provide any family or staff member with a laptop to work at home during this time,” GISD Executive Director of Communications Melinda Brasher said in an email.

As for meals, GISD moved from serving meals twice daily to once a day where students would receive a hot lunch and a prepackaged breakfast for the next morning.

Brasher said at the time the decision was made for multiple reasons, including safety for everyone by having a once-daily engagement in the community. She added it is more efficient for families to pick up once daily, and it reduces the number of staff needed for distribution.

About 40% of the district’s students qualify for free and reduced meals, Sanchez said. But GISD was determined to also feed the families of its students, distributing 6,042 meals to adults between March 23 and March 31, as the district wanted to provide for anyone who came through its meal line. This move added $19,800 in expenses.

District officials said distributed meals to adults do not qualify the district for reimbursement through the Texas Department of Agriculture free and reduced program for students, but the district plans to be able to get reimbursed through federal coronavirus-relief funding.

However, prepackaged meals are more expensive than warm meals. And the district is having to pay essential staff a premium—or time and a half—for working in a high-risk environment, Sanchez said. This includes custodians, food workers and technology distributors.

“We’ll receive reimbursement, [but] that reimbursement probably won’t cover all of our salaries,” Sanchez said.

In addition, the food service fund—which is separate from the general fund for operations—is replenished by students who pay for their meals in addition to federal funding. But since students are not eating at school, that money is not coming in, Sanchez said.

“Regardless, food is a basic need, and we wanted to help provide for any GISD family member in need during this time, no questions asked,” Brasher said. “We know that some of our families were experiencing loss of wages due to partial furlough and/or layoffs. Helping provide food allowed them to use their available funds for other basic needs while keeping their family fed.”

District savings

The district has also saved money while campuses are closed, primarily in utilities such as water and electricity.

With district facilities closed, GISD expects a reduction in utility expenses by about 23% for March compared to last year, officials said.

Additionally, most of the buses are not on the road transporting students. While it is not as easy to estimate year-over-year savings due to the lower price in gas, GISD anticipates a savings of about 46% in fuel and maintenance compared to last March, officials said.

Sanchez said the district expects to save a little more than $70,000 in March.

“Yes, we’ll have savings and utilities fuel, that kind of thing, but we were also spending in another area that may not be covered from any type of funding from the federal government,” Sanchez said.

House Bill 3

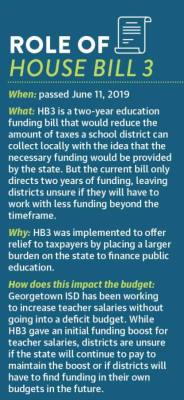

Sanchez said the second year of implementing House Bill 3—described by legislators as one of the most extensive school finance reform bills in Texas history—will also impact the district’s budget.

HB3 reduces the property tax rate districts can set on residents and puts the burden of school funding on the state. But the bill was only funded for two years, and the state’s economy is taking a toll due to the pandemic.

“The economy is being impacted, and the state budget that the Legislature has to work with ... will definitely be much less,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez added that much of the budget predictions are just that—predictions—as the full impact of the coronavirus remains uncertain.

So while the district continues to look at strategies to increase teacher salaries—a top priority for the district and board and something that has been in the works since before the pandemic—Sanchez said officials want to do it in a sustainable way so that increases remain even as budgets and funding sources may change.

“We will be working once again every day in June to get the budget as mindful for our community and financially sound for our taxpayers in our community to be sustainable through future years, but also take care of our current staff and teachers and stay competitive with our neighbors,” Sanchez said.

Teaching from a distance

The coronavirus has also impacted how grade-school teachers approach their jobs.

To help educators prepare for distance teaching, GISD offered district-sanctioned optional learning for the first two weeks after spring break with graded work beginning April 6. This allowed its teachers to figure out how to convert their lessons virtually and from seeing their students face to face to seeing them on a screen. But the distance was not easy.

“I didn’t sign up for online teaching; I want my kids here with me,” Purl Elementary School teacher Diane Collman said. “A lesson is hard online, but in person, it’s a lot easier to go to each kid and see what they need.”

Collman said distance teaching has been a huge learning curve.

Her in-classroom plans have been made virtual, and the original curriculum has changed. She is also learning how to care for individual student needs from a distance, something that has been difficult for her, she said.

Janie Wiley, a fifth-grade reading teacher at Frost Elementary School, said for her, ensured accountability is one of the hardest parts of distance teaching.

The district recommends those in eighth grade and below receive two hours of instruction a day, and high school students receive four hours a day. Currently students in elementary and middle school are functioning on a complete or incomplete grading system. Those in high school continue to receive graded work.

“The biggest problem has been the accountability at home with the family. [The district has] given them all the technology, and [teachers have] done the work,” Wiley said. “Now it’s kids getting on and doing it.”

Wiley said in her experience transitioning to virtual teaching was streamlined, with the district providing plenty of resources and time for teachers to figure out their lessons. But her lessons have completely changed to stripped-down, big-idea concepts rather than deeper, more detailed lessons.

And while Wiley is checking in on her students as much as she can and is readily available to answer questions during her office hours, she said nothing compares to being in a classroom with her kids.

“Without that human component being right there with my kids, I can’t tell if they’re learning or if they’re understanding the concept, which is why I really want to meet with them a lot,” Wiley said.

She said there is method in the little second-by-second decisions she makes in the classroom to clarify or give an extra example to a student she can clearly see is not understanding.

“To do my craft with my kids and the relationships, that’s what I miss so much. [It’s] being with them and working through their problems and helping to raise them, really,” Wiley said.