Final design decisions from TxDOT likely will not come until 2022, but many city leaders and community members say the project as it stands does not meet Austin’s goals.

Jay Blazek Crossley of transportation nonprofit Farm & City called the three design concepts presented so far “three different lipsticks on a pig” that reinforce I-35 as a dangerous barrier rather than chiseling away at it.

“It’s the last gasp of an old failed system, and the people of Austin are going to have to pay the price of the 20th-century freeway building regime crumbling,” Crossley said.

The project plan

TxDOT is still in the process of making decisions, which include the elevation of highway lanes and the placement of ramps and frontage roads. The federally mandated public comment period ended April 9, but the state agency is still holding community working group sessions, including one that was held April 15.While much of the design is still to be determined, TxDOT is working from a starting point for the project handed down from political leaders and the Texas Transportation Commission. TxDOT officials say part of their task is to add capacity, which will come in the form of two high-occupancy, or HOV, vehicle lanes in each direction for public transit, carpools, vanpools and emergency vehicles.

“The HOV lanes are going to incentivize transit and people carpooling. That’s going to encourage more people to drive together and provide more capacity on the highway,” TxDOT Program Manager Susan Fraser said.

All three conceptual designs TxDOT has released so far propose to tear down the upper decks between Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Airport Boulevard. They also would lower the main lanes for the most urban stretch from Lady Bird Lake to Airport.

Commission Chair J. Bruce Bugg vowed in February 2020 the state would go “no wider and no higher” with this project, instead opting to dig deeper to add capacity. But many transportation advocates disagree with the decision to expand the number of lanes on I-35—pointing to transportation research showing added lanes do not solve capacity issues.

Heyden Black Walker is an architect, urban planner and one of the creators of the Reconnect Austin plan, a proposal to bury the main lanes of I-35 from Lady Bird Lake to Airport to reclaim public space and stitch together east-west connections. Black Walker said even with the restrictions, there are still ways for TxDOT staff and engineers to create a project that works.

“Really, all they can do is build a highway, which is the wrong choice. But if you’re going to build a highway, there are choices they can make that would be a better highway,” she said.

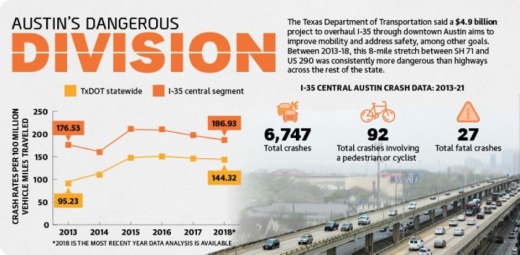

Many of those choices come down to designing the highway in a way that allows local entities to build on top of the roadway. The $4.9 billion in TxDOT project funding would not pay for proposals such as Reconnect Austin, or Rethink 35, which would create a surface-level boulevard where I-35 now sits—money for those would have to come from the city or its partners. The Downtown Austin Alliance has brought community members together to create that local vision for the project.

“We want to be able to give a vision for what happens above the highway, and that is a way for building in options for the future of mobility as it changes,” said Emily Risinger, planning and urban design manager for the DAA.

I-35’s legacy of division

To be successful, community activists and local leaders say the I-35 project has to recognize the highway’s history as a racial and social barrier. That history traces back to the city of Austin’s 1928 Master Plan, which created a “Negro District” in 6 square miles on the east side of East Avenue, now I-35, and forced nonwhite residents to move to that area.That forced migration depressed property values and robbed communities of color of the chance to build generational wealth through housing, according to Bo McCarver, vice president of the Blackland Community Development Corp., a nonprofit that creates and maintains housing in Central East Austin’s Blackland neighborhood for low-income families.

Although Austin would officially abandon its 1928 Master Plan by the 1950s, when I-35 was built, the construction of the highway created an indelible line through the middle of the city.

“You can destroy a community real easily; it’s harder to build one,” McCarver said.

Ideas to recognize I-35’s legacy and translate that into construction are still in the early stages. They include more pedestrian and bicycle crossings, public spaces on the right of way that could be used for affordable housing or cultural events, and design standards mindful of the environment and air quality. As a start, advocates say TxDOT could acknowledge the history in its purpose and need statement—a federally mandated summation of the project’s goals.

Whatever shape the solutions take, District 1 City Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison said for her, success comes down to ensuring Austinites can get around the city without equipping themselves with “two tons of steel and rubber every time they leave the house.”

“Removing the physical and social barrier is the first step, connecting the city east to west. Any highway plan that doesn’t include that is not favorable to me,” Harper-Madison said.

Early in 2020, a panel of experts from the Urban Land Institute met with hundreds of Austin residents and researched I-35, then presented their findings at a discussion at Huston-Tillotson University. The report pointed to some other successful examples of highway cap-and-stitch or deconstruction projects around the country.

In Dallas, the 5.2-acre Klyde Warren Park covers a section of the Woodall Rodgers Freeway downtown. In Boston, the Rose Kennedy Greenway connects some of the city’s oldest neighborhoods after it replaced an elevated section of highway that moved underground as part of the city’s “Big Dig” project. More connections that help people get around more easily are what District 4 Council Member Greg Casar said he needs to see before he can support the project.

“The current TxDOT designs are doubling down on the design of the 1950s—it’s a big highway that cuts through our city and separates it,” Casar said.

A critical moment in Houston

Tom Wald is the executive director of the Red Line Parkway Initiative, a nonprofit supporting the proposed park and public space from downtown Austin to Leander. Like other transportation advocates, Wald has a healthy amount of skepticism that TxDOT will listen to the community and act on the comments submitted.“It’s going to be [designed for] people on the edges of the city who want a shorter commute—until traffic backs up again. It’s not going to benefit people who live in Central Austin. That’s not who the project is for,” Wald said.

But recent events in Houston show that local governments may have more tools at their disposal to advocate for themselves. Harris County sued TxDOT in federal court on March 11, arguing the planned $7 billion overhaul of I-45 violated federal law by not adequately considering the environmental ramifications. At the same time as the lawsuit was filed, the Federal Highway Administration wrote to TxDOT asking the state agency to pause the project.

TxDOT officials noted the I-45 project is very different from the proposal for I-35. In Houston, the project would have displaced over 900 residents, 300 businesses, five places of worship and two schools, a level of disruption that would not happen in Austin.

“We are following the lawsuit, talking to the Houston district, and we very much want to understand the issues and to take away lessons from that,” Fraser said.

The I-35 project is in an earlier stage than I-45. Harris County sued after TxDOT filed its final environmental impact statement, a federally required step that would not happen in Austin until 2023.

Still, Black Walker said she hopes what happened in Houston is a wake-up call for TxDOT that forces the agency to re-approach the way it deals with urban areas.

“TxDOT is good at building rural highways. They’re bad at building in urban places,” she said. “And they end up reinforcing the racial barriers that put [the highways] there in the first place.”