“Why the color of my skin brings fear to people, I don’t understand,” she said.

The city of Austin and Capital Metro will ask Austin voters in November to fund a plan that would connect neighborhoods such as Colony Park to downtown through public transportation.

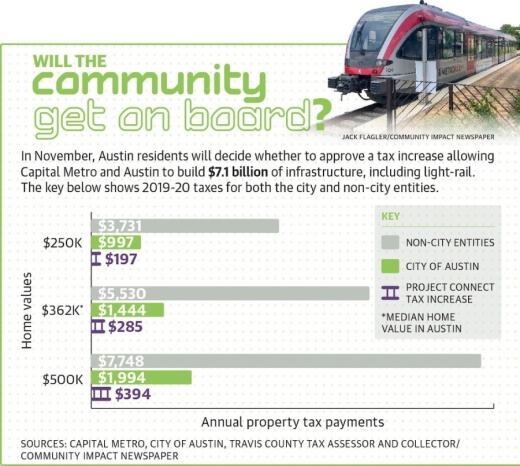

Project Connect, a $7.1 billion investment with about $3.85 billion coming from local property tax funds, would include two light-rail lines, an additional commuter rail line and a downtown underground train station.

Cap Metro's board of directors initially approved a $10 billion plan, and expansions, such as an additional light rail line running from ACC Highland to South Austin, could come years down the road if more funding is available—but voters in November will only be deciding on the tax rate to fund the initial investment.

Local leaders say improvements are long overdue to address traffic and provide transit access to residents who do not own vehicles. But they also recognize challenges of inflating home values along the transit lines and deepening divides.

Baked into Project Connect is a $300 million investment intended to make sure the new public transportation lines are built for the people to serve the people in the neighborhoods they will traverse, not drive them further out to Austin’s periphery.Travis County Commissioner Jeff Travillion said he does not want to repeat the mistakes previous governments made when they made I-35 a dividing line between the rich and the poor.

“What I fear most is that [US] 183 is becoming the [I-]35 of our generation,” Travillion said.

Traffic problems multiply

Austin’s population surpassed 1 million residents July 1, according to projections from city demographer Ryan Robinson, and projections from the Capital Area Council of Governments show the number of people in the 10-county Central Texas region is expected to balloon from about 2.4 million residents to roughly 4.1 million people by 2040.U.S. Census data from 2018 shows that about three out of four Austinites commute to work by driving alone.Even if work behaviors change after the coronavirus pandemic, Capital Metro President and CEO Randy Clarke said traffic will continue growing significantly worse as the population grows if Austin does not take action.

“Every human being that moves here for the next 20 years would have to work remotely to have the same rush hour we had in February—100% would have to not touch a car during rush hour in order to not have the traffic we had before the pandemic,” Clarke said.

Austin resident Brandon Miller runs a firm that specializes in consulting and marketing for residential home developers and focuses on neighborhoods along South Congress Avenue, where the proposed Orange Line would be built. He said for more than 15 years he has wanted the city to be more aggressive when it comes to light rail.

“Austin needs to get to the point where not everybody needs a car,” Miller said.

The benefits, Miller said, would likely extend to housing prices in new developments. If Austin built a light-rail system, the city would be in a better position to lift its current requirement that necessitates at least two parking spaces for every single-family home, duplex unit or townhome.That, Miller said, would make housing cheaper to build. He said each parking spot costs developers about $40,000 to build.

“Developers are losing money on parking. Eventually that cost has no choice but to be baked into the price of the home,” he said.

However, the price of existing housing around the light-rail lines would likely increase because of the new options to get around the city. That is a benefit for property owners if they want to resell their house, but the resulting increase in taxes also has the potential to overburden homeowners.

A 2014 study from the University of Minnesota found that when an 11-mile light-rail line was built between St. Paul and Minneapolis, home values increased by $13.70 per square foot between the announcement of the federal grant in 2011 and operations starting in 2014

“Displacement is imminent with a light-rail system. You better have all your anti-displacement and affordable housing initiatives penciled in from the beginning,” said Carmen Llanes Pulido, executive director of Go Austin Vamos Austin.

GAVA is a nonprofit that works with Austin communities to build programs that improve access to health. If Project Connect were built in an equitable way, Llanes Pulido said, she has no doubt it would have a “phenomenally positive impact.” But she said the communities GAVA serves have little faith in the city to execute its promises because Austin’s history is full of broken promises.

“This is my biggest concern,” Llanes Pulido said. “There is not a track record of action or fulfillment.”

‘The opposite playbook’

‘The opposite playbook’

District 1 City Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison has spent her entire life in Austin. She knows in 1962, when I-35 opened in Austin, it deepened a segregating divide. And in 1971, when MoPac was built, homes in Clarksville, a historically Black neighborhood on the west side of the Missouri and Pacific railroad tracks, were destroyed, according to the Clarksville Community Development Corporation.But Harper-Madison said the city can get this right if it is acts quickly and invests the $300 million intelligently. She said the opportunity is there to build a system that exists not as a source of shame, but as something residents can take pride in.

“I see Project Connect as a chance to run the opposite playbook of what we did in the past,” Harper-Madison said.

Clarke said the $300 million investment is “unprecedented” among cities that have taken on major public transportation projects recently. The exact uses of the money have not been spelled out specifically, but options include buying land to build affordable housing, home repair, rental subsidies and financial assistance for home ownership.

Elizabeth Mueller, a professor at The University of Texas School of Architecture, said $300 million alone would not go far enough to address the pressure of gentrification. The key for Austin will be leveraging the money with grant opportunities, nonprofit partners and other sources of revenue—and the city will need to act quickly.

“How can you act fast enough to buy some of these places before people are getting pushed out?” Mueller said.

Heather Way—a professor in UT’s School of Law and co-author with Mueller on “Uprooted,” a 2018 report that studied gentrification in Austin—said research in other cities has shown that if voters approve Project Connect, the impacts on home values could be felt as soon as the votes are counted.

“We can never do enough; we can always be doing more; but the city has really taken some good steps in the right direction,” Way said.

Those steps are a vast improvement from 2000, when Capital Metro made its first attempt at a light-rail plan, according to Travillion, who was president of the NAACP’s Austin chapter until 1997. Back then, there was little outreach to Black communities.

Scott remembers that time in Austin as well. She welcomes the Green Line and the mixed-use project developer Catellus is planning on a 208-acre city-owned site. Sergio Negrete, senior development associate at Catellus, said the large mixed-use project in the area is guided by the community, and the developers hear "loud and clear" that access—including transit—is a high priority for residents.

But even if voters approve Project Connect on Nov. 3, Scott said the neighborhood cannot wait until transportation lines and new housing units are built to see investment. Currently, there are no library branches or supermarkets in her neighborhood.

"We can’t wait for the Green Line for the grocery store,” Scott said. “We need the grocery store now.”