On May 21, a moment eight years in the making took place in Austin, but it did not happen as it was envisioned.

Instead of an on-campus celebration, the 49 members of the first graduating class at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas watched the virtual ceremony on their screens. Then, they started their careers as residents, where Dell Medical School dean Dr. Clay Johnston said they are prepared to be “change agents” for a health system he said is in crisis. In Austin, that crisis has been felt most significantly by the city’s minority residents.

“It’s the responsibility that I’ve been looking for,” said Dr. Anatoli Berezovsky, a Dell Medical School graduate who began working as a family medicine resident in Fort Worth in June.

In Austin, the connections between the coronavirus and issues such as food insecurity, transportation access and systemic racism—challenges the students at Dell Medical School have been studying as part of the school’s holistic approach to medicine—have amplified existing divides in the city.

According to 2014-18 five-year estimates from the U.S. Census American Communities Survey, the city's population is roughly half residents who identify as white-only and one-third Hispanic or Latino residents. However, according to Austin Public Health data, Hispanic or Latino individuals have accounted for more than 57% of coronavirus hospitalizations every week from April 26 to June 14, while white residents have accounted for less than 30% of hospitalizations.

“This has revealed just how fragile health is for certain segments of our population. We knew it; we were anticipating it; we were watching for it. We couldn’t prevent it,” Johnston said.

A crisis for those most at risk

In September 2018, Dell Medical School brought in Dr. Jewel Mullen to serve as its health equity dean. Mullen’s role, as she describes it, is to ensure that Dell Medical School’s leadership reflects the mission that students sign up for—working toward equitable health care. Her work has not changed in the last three months, but as she has watched companies deliver statements on the pandemic and protests against police violence, she said the importance of strong leadership is clear.

“Lots of organizations have made their statements about standing against racism and inequities. What I say is actions speak louder than words,” Mullen said.

On June 10, in the midst of a spike in local coronavirus cases, Dr. Mark Escott, Austin-Travis County interim Health Authority, delivered a similar call to action.

“We have to work harder as a community to address these inequities. We simply have not done enough, and quite frankly I think it’s inexcusable as a country that in 2020, we don’t have access to care for all members of our community,” Escott said.

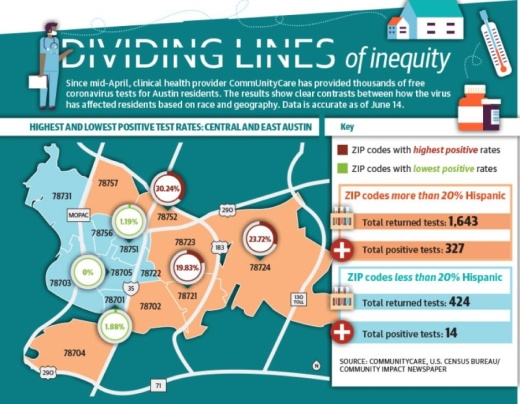

Since mid-April, CommUnityCare, the clinical arm of county health provider Central Health, has been testing individuals for free at locations throughout Travis County.

Data from the tests CommUnityCare has provided shows lines in the community drawn around geography and ethnicity. Clients served in Spanish had a 30% positive test rate through June 14, according to CommUnityCare, while those served in English tested positive at a rate of 9%.

Mike Geeslin, president and CEO of Central Health, said it is difficult for many Austin residents to isolate safely and protect themselves from the coronavirus. That could be true if those individuals have jobs that do not allow them to stay home, or in their family life, if they have a number of family members living in the same household.

“The COVID pandemic has revealed inadequacies and discriminations that have long existed, continue to exist and have been ignored for decades,” Geeslin said.

Dr. Kim Kjome has seen the same divide in Austin when it comes to mental health. Kjome is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Dell Medical School and the medical director at Ascension Seton Shoal Creek, where she still sees patients one on one.

Kjome said she has seen a huge increased need for mental health care since the pandemic began, but at the same time many patients’ access to care has been cut off because of increasing unemployment and loss of benefits.

“It’s very hard to live in Austin if you don’t have money, and if you lose your job, you can become very challenged,” Kjome said.

Measure Austin, a local advocacy organization aimed at eliminating social disparities, released results of a survey June 1 that highlighted specific issues related to the coronavirus in Austin.

The survey showed 32% of non-white respondents reported having trouble with food assistance, compared to 11% of white respondents. There was also a gap in questions related to housing—59% of white respondents said they “strongly agree” they have the ability to pay rent for the next three months compared to 53% of non-white respondents.

Meme Styles, founder and president of Measure Austin, said the results, along with recent protests against social injustice, show Austin is not as progressive as the city likes to believe.

“When we're hit with a pandemic—or an uprising—that’s when your true progress is tested. We failed the test when it comes to COVID-19,” Styles said.

The post-pandemic future

In a June 11 memo written to Mayor Steve Adler and Austin City Council about the city’s response to the coronavirus disparities, APH acting Director Adrienne Sturrup wrote that the response and recovery from the virus are expected to continue through 2021.

In a June 11 memo written to Mayor Steve Adler and Austin City Council about the city’s response to the coronavirus disparities, APH acting Director Adrienne Sturrup wrote that the response and recovery from the virus are expected to continue through 2021.

Jay Fox, president of Baylor Scott & White Health for the Austin and Round Rock region, said one challenge during this time will be to continue navigating the pandemic while helping communities see hospitals and clinics as a safe place to receive care for other needs.

Telemedicine may be a part of the long-term solution, according to experts and care providers. Ascension Texas, CommUnityCare and Baylor Scott & White all reported conducting more than 60% of their appointments via telehealth over the last few months, a trend that may continue after the virus is gone to provide patients an avenue for care that does not require a trip to the doctor.

For Central Health, the growing Innovation Zone at the northeast corner of downtown Austin is a major piece of its ability to care for Austin residents in the post-pandemic future.

The county health provider owns 14 acres of land at the site of the former University Medical Center Brackenridge Hospital. Demolition is underway to make way for a 17-story office tower that will house some of Dell Medical School’s offices. Central Health will receive more than $5 million in lease and rent revenue over the next three years to fund its outreach efforts to underserved communities such as Hornsby Bend, Colony Park and Del Valle.

Another milestone for the zone will come July 30, when City Council will have a hearing on a zoning overlay for Central Health’s property laying out the restrictions and uses for future redevelopment. Michele Van Hyfte, vice president of urban design at the Downtown Austin Alliance, said it will be another step toward making the zone a reality.

“We’re very excited it’s gone from an idea to construction,” Van Hyfte said.

Geronimo Rodriguez, chief advocacy officer for Ascension Texas, has been working with the health care provider since 2006 on issues such as workforce development, diversity and inclusion. He said he hopes the pandemic and the protests will shift the community’s perspective.

“They have either broken people or broken them open. If they break someone, they’re leading them to being hard-hearted. I think a lot of people are breaking open, leaning in, striving and desiring to be in community with their fellow human beings,” Rodriguez said.

Mullen said the path to truly creating a more just health care system in Austin will require more than technical improvements such as increasing use of telemedicine and the construction of the Innovation Zone—it will require community leaders turning the mirror on themselves.

“What’s the system we want to build so that we don’t apply some new technical solutions, but never fix the underlying problems to eliminate the disparities? That’s hard. But that’s transformational leadership, and that’s what this time calls for,” Mullen said.

Christopher Neely contributed to this report.