“As an African American who attended a public school district, I saw firsthand how students were not being pushed into college,” he said. “Black and brown students who grew up in communities similar to mine are not being able to receive the education they deserve, and in my eye, we give them that at IDEA.”

Since the first public charter schools were established in Texas in 1997, charters have offered a free alternative to parents and students who may not have found success at a traditional public school.

With almost 750 charters open across the state serving 316,775 students according to the Texas Education Agency, operators tout prioritizing goals such as college readiness, dropout recovery and serving at-risk populations. TEA data shows 70% of students in charter schools are classified as economically disadvantaged, 10% higher than in public school districts.

However, while charters educate 7% of Texas students, their operations take up more than 15% of the state’s education budget. Unlike public districts, charters cannot generate property tax revenue or hold bond elections to raise funding. As a result, they are fully funded by the state and on average receive $1,150 more per student from the state than a public school district.

The number of charters in Texas has almost doubled since 2010, and some legislators fear that charters are hindering the ability for all schools in Texas to be adequately funded. This legislative session lawmakers have filed 18 bills related to charter school funding or expansion as of March 15.

“We’ve seen a trend over the past decade that more and more state dollars are going to charter schools,” state Rep. Donna Howard, D-Austin, said. “We have a system that is allowing them to grow, and that is not sustainable.”

Growth and funding

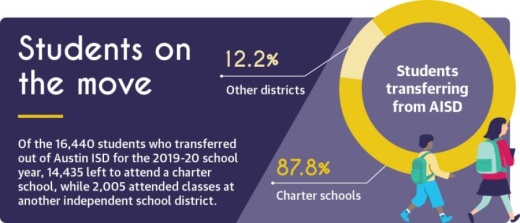

There were two charter schools located within Austin ISD’s boundaries in 1997. Less than 25 years later, there are 58 in the area, with 14,435 active students who live in the district attending those schools.AISD Director of Policy Edna Butts said charters have hurt the district financially because each student who attends a charter school takes state funding with them. However, more often than not, the operating cost for the district remains the same, she said.

Starlee Coleman, Texas Public Charter Schools Association CEO, said parents need options, especially in areas such as Austin’s Eastern Crescent, where she said there has historically been an income and school performance divide.

“The notion that charter schools are taking money from ISDs is unfortunate, because funding does not belong to any school system. It belongs to the student,” she said.

Coleman said demand from parents has driven growth over the past decade.

However, Bob Popinski, the executive director of education nonprofit Raise Your Hand Texas, said a growing coalition of school districts have been adversely impacted by charter schools. Popinski said the approval system used to fund new campuses lacks transparency. He said the state does not allow for enough public feedback or give school districts an adequate way to defend their own school’s performance, resulting in expansion efforts that go unchecked.

Charter organizations are approved through an application process with the TEA, in which the school outlines its goals and why it believes it can serve the community, Popinski said. The application is then reviewed by the State Board of Educators, which can approve it. Once approved, however, there is less oversight about expanding programs.

Expansion proposals are reviewed by the TEA commissioner, who has the sole authority to approve or veto. Because of this, Popinski said charters can expand quickly and without oversight by an elected board, even in areas already served by highly rated schools.

“You can have a district providing these great programs at a school, and then a charter school is built right next door,” he said. “A new charter can throw a wrench into good, transparent district planning.”

Adding transparency to the process

Popinski said school districts in the state are asking lawmakers during the current legislative session to install more oversight in the charter expansion process and to limit new charters during the ongoing pandemic.“It’s not particularly fighting against one application or expansion,” Popinski said. “It’s making sure the whole system works.”

The Texas Schools Alliance, which is made up of 43 districts including AISD, released a letter to the State Board of Education in August asking the board not to approve new charters due to the impact they would have on the state’s budget. The letter was endorsed by 20 additional education groups, including the Texas Association of School Boards. In 2020, the board approved five of the eight new applications submitted, including one in Austin.

Howard, who supports efforts to balance charter funding, said due to added education cost caused by the pandemic, now is not the time to consider approving new charter schools and added oversight could help slow future growth.

“There obviously are students who are benefiting from charters, but taking funding and resources away from our district schools does not seem to be viable,” Howard said.

At least four bills filed in the state House look at transparency in the approval process. Two filed by state Rep. Mary Gonzalez, D-El Paso, would increase the notice given to cities and school districts about a new school, require charter schools to provide more details about proposed new school locations and asks the TEA to consider if a charter has achieved the goals outlined in their applications before allowing one to expand, according to the bills. State Rep. Vikki Goodwin, D-Austin, submitted House Bill 438, which would require similar increases in charter transparency and calls for a more thorough review of applications. Also filed by Goodwin, HB 2744 would aim to close the state funding divide.

Butts said AISD, which supports the above legislation, believes charter schools offering specialized programs can be a boost for the community. However, too often she said a charter’s mission and execution do not match.

“We’re asking TEA to go back and look at their data from the past to show if their goal was met before letting them expand,” she said.

HB 97, filed by state Rep. Gina Hinojosa, D-Austin, would require charter schools to accept students with disciplinary histories who request enrollment. Currently, Butts said charters have permission to deny such students admission, leaving some of the most vulnerable students in the community without options. HB 108, also filed by Hinojosa, would require charter to follow the same expulsion criteria as public school districts.

Education options

Kathleen Zimmerman is the executive director of Not Your Ordinary School, a K-12 charter school in North Austin. NYOS follows a year-round learning schedule and offers smaller class sizes. She said the result is an environment that is different from what AISD schools offer and a long waitlist of future students.NYOS will double its footprint this summer when it moves into a new campus that the school is funding through state dollars and philanthropic financing.

“It wasn’t about building a school just to have one,” Zimmerman said. “We know we have something special here; there’s demand for it; and the community believes it.”

She said securing facilities funding in particular has been a long-standing problem for charters, which often have buildings that Zimmerman said pale in comparison to district schools.

Charters can also face increased regulation from cities and counties, Coleman said. A top legislative priority for charters this session is to make the development process more equitable.

Sen. Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston, and Rep. Harold Dutton, D-Houston, filed companion bills that would remove “red tape” for charter schools aiming to secure land for facilities. Bettencourt said his hope is to remove obstacles that require charters to spend additional state money during development.

Dutton has filed three other bills related to new campuses and allowing charters to apply for career and technical education grants.

Coleman said increasing the state’s education budget overall would pay dividends later for Texans and local educators.

“All public schools need to be well-funded,” she said. “We need to be able to have great facilities, and we need to be able to pay our teachers the salaries that they deserve.”