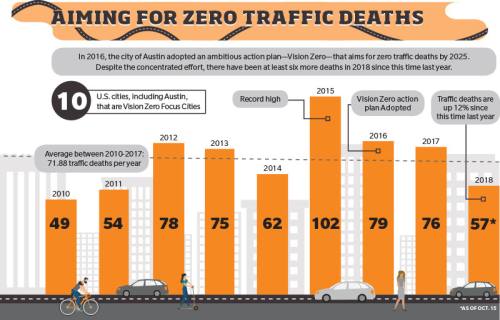

As the plan approaches its third year, traffic fatalities are on pace to exceed the city’s average

Intersection improvements. Downtown’s new Sobering Center. The scooters. Austin Police Department officers riding a Capital Metro bus looking, from their perch, for drivers who are texting.

These are some of the initiatives that fall under the city of Austin’s Vision Zero action plan, which City Council adopted in 2016 following a record-high year for traffic fatalities.

It was produced by a network of partners, including the city’s planning and zoning, police, public health, public works, and transportation departments; the bicycle and pedestrian advisory councils; the Mayor’s Committee for People with Disabilities; local nonprofits; Capital Metro; and the Texas Department of Transportation.

The goal? To reach zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2025.

As the plan enters its third year, however, at least 57 people have died in Austin in 2018, a nearly 12-percent increase from this time last year.

“I think it is difficult to have an expectation on an issue that is so complex and [for which] the solutions demand such a broad spectrum of action,” said Laura Dierenfield, active transportation program manager for the Austin Transportation Department.

In line with the plan, city staff and safety advocates agree that traffic fatalities will decrease only when there are fewer cars moving at lower speeds on higher-density streets shared with people using other forms of transportation: bikes, dockless mobility, public transportation and their own two feet.

But they also acknowledged that, in a city full of commuters with a developing public transit system, this is a hard task.

Car culture

The post-World War II economic boom spurred the growth of America’s middle class, as did the G.I. Bill, which provided money for veterans to purchase homes.

In response to increased demand, automobile production quadrupled between 1946 and 1955, according to the U.S. Department of State.

Then, in 1956, Congress passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which provided over $100 billion to develop a 41,000-mile interstate network, solidifying Americans’ dependence on driving.

“People say that Americans love their cars, but it’s also deeply true that cars are not just a way of getting from point A to point B. [They are] a status symbol,” said Alex Karner, an assistant professor at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

Today more than 350,000 people commute into the city of Austin each morning, 80 percent of whom drive alone, per data collected between 2002 and 2014 by the U.S. Census Bureau.

For many commuters, some who live as far as Georgetown and San Marcos, cars are the obvious option.

“Public transit in the U.S. in the vast majority of places has never really worked super well,” Karner said. “It doesn’t really provide a high level of service that’s comparable to driving.”

On roads built for speed, other forms of transportation pose risks as well as inconvenience. Per the plan, people walking, biking and riding motorcycles account for less than 7 percent of traffic in Austin, but over half of traffic deaths.

Follow the data

With so many partners involved, data collection and sharing between departments, across agencies and with the public is paramount.

The plan lists a number of goals to facilitate this, including funding regular cyclist and pedestrian counts, providing training and technology for officers to better record crashes and their causes, and creating an interactive online tool to display the collected data.

These initiatives help city staff know, for example, which intersections are most dangerous and in need of the $15 million allocated for safety improvements in the 2016 Mobility Bond.

In those intersections that have been improved, preliminary data from ATD shows an annual overall crash reduction rate of 21 to 56 percent.

Keeping the law

Enforcement is another major focus area of the plan, which listed the creation of a DWI prosecution unit and funding for red-light cameras as goals.

APD sent officers out in unmarked cars to identify distracted drivers and launched its No Refusal initiative, which helps officers more easily obtain search warrants for blood samples from drivers who refuse a breathalyzer test.

Still, the department responded to over 15,000 crashes in 2017, more than 41 a day, according to TxDOT.

Crash management strains the understaffed department, said Patrick Oborski, a detective with APD’s Highway Enforcement Command, and some officers spend up to 90 percent of their time responding to collisions.

The work also takes an emotional toll.

“The first autopsy I ever saw was on a 4-year-old” who died in a crash, Oborski said. “You get broken in real quick.”

Intelligent design

Engineering—which includes land use, infrastructure improvements and street design—and education are the third and fourth pillars of Vision Zero.

Per the plan, “Lower density, longer blocks, large parking lots and free or low-cost parking, frequent driveways, and lack of street connectivity directly contribute to higher traffic deaths.”

But efforts to increase density, such as CodeNEXT, have met strong resistance.

“Even with our current land-development code, there are a lot of things that we can do as a city to address safety,” Dierenfield said, citing ongoing efforts to add and rehabilitate miles of sidewalks, urban trails and bike lanes.

ATD staff are also in the process of drafting the Austin Strategic Mobility Plan—a guide to transportation policies, programs, projects and investments over the next 20 years—and plan to present it to council for adoption in early 2019.

In the meantime more can be done to disincentivize driving, advocates said.

“Take one darn car parking space per block. Boom. Put a [bike rack] there. You’ve got 12 bikes,” said Katie Smith Deolloz, interim executive director of the local advocacy group Bike Austin.

Such infrastructure improvements, Deolloz said, should also accommodate Austin’s new dockless mobility options.

By offering an alternative to cars for short trips—those under 3 miles—dockless mobility helps reduce traffic congestion and fill the gaps in the city’s public transit system, said Trevor Theunissen, a spokesperson for Uber, which owns electric ride-share service Jump Bikes.

While Austinites have raised concerns about the safety of dockless mobility technology, city staffers embrace it. “Cities where more people are walking and biking and taking transit are generally safer for everyone,” Dierenfield said.

Policy goals

While committed to the plan, the city of Austin is not the only player.

“A lot of the policy that really drives the Vision Zero plan is ... outside of the city’s direct control,” Dierenfield said.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has criticized the city’s corridor mobility plan, and speed management bills have failed to gain traction at the Capitol.

Jay Blazek Crossley, chair of the Pedestrian Advisory Council, said he hopes this changes in the 2019 session.

“The car transportation system is the safety problem,” he said. “Although missing sidewalks are less safe [and] missing ramps are a problem, what’s going to kill you is a car driving too fast.”

In the absence of meaningful speed-management reform and broader cultural change, Blazek Crossley said the city, at least, is on the right track.

“Vision Zero has changed the culture in Austin and how the city looks at things,” he said. “In terms of long-term planning, it’s been extremely effective.”