“Being in the restaurant, it’s like we’re putting on a show every night,” Eldorado Cafe owner Joel Fried said. “The server comes up, does their spiel, the chefs are doing their artistic thing in the back, managers are walking by; it’s just the whole vibe thing. And then when you don’t have that [customer] interaction, the show’s different.”

Fried acknowledges that market conditions are forcing restaurants to make tough choices but has maintained a traditional customer service model.

Texas Restaurant Association data shows 86% of restaurants in the state raised their prices since 2019.

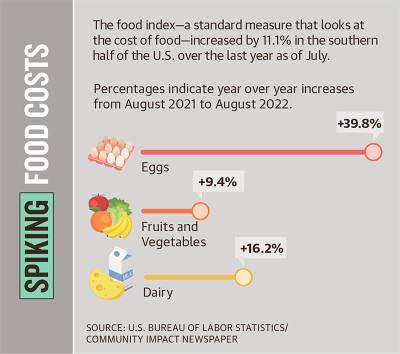

The food index, which measures the change in price of a standard basket of food—including items, such as eggs, milk, produce and meat—rose 11.1% since last year as of July, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

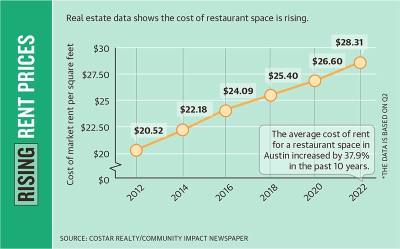

“When you throw in labor and food and real estate taxes, it’s like a perfect storm,” said Amir Hajimaleki, owner of Silkhouse Hospitality group. “They all hit at the same time. I think that’s why a lot of places have gone out of business.”

More than 90% of restaurants in the state raised their prices since 2019, according to the TRA.

“[Restaurants] have gone through trial by fire over the last two and a half years. And so what we encourage them to do is exactly what we’re seeing in the market, which is adapt [and] know that this inflationary cycle will not last forever,” said Kelsey Erickson Streufert, chief public affairs officer for the TRA.

Pressure on local restaurants

Of the more than 30 Austin restaurants that Community Impact Newspaper reported closing this year, many owners cited food costs, labor shortages or burnout. Those restaurants included the Bill Miller Bar-B-Q and Lucy’s Fried Chicken location on Burnet Road, Sweet Ritual, The Way Far South Philly Deli, and Sala + Betty.

Kristin Collins, owner of the bakery Fluff and Meringues in North Central Austin that closed in July, said that the decision to close “made itself for [her],” pointing to inflation in food, rent, fuel, permit prices and packaging. Collins said at the time she closed, revenue was actually increasing, but she could not outpace inflation. The price change of eggs alone cost her businesses an extra $800 a month, she said.

“There were people who really loved it and depended on it, and in a weird way, I feel like I’m letting them down,” she said.

Hajimaleki, owner of several Austin spots, including Keepers Coastal Kitchen, District Kitchen + Cocktails, Oasthouse Kitchen + Bar, and Shortie’s Pizza and Grinders, said he is constantly evaluating his business practices to keep his restaurants going.

Hajimaleki said while his food supply cost was raised around 15%, he only raised the prices on the menu 8% to retain customers. Hajimaleki also opted for QR code menus and ordering via phone instead of with a server for his seafood restaurant Keepers in Southwest Austin.

“The dining experience happens at the table over great food. So whether you’re ordering from a server or ordering on a QR code, to me personally, doesn’t change that,” Hajimaleki said.

Hajimaleki said he continues to prioritize the quality of the ingredients on his menus and staff compensation.

Despite his challenges, Hajimaleki said owning several restaurants in the area has helped keep business afloat, as his consistently profitable locations balance out the newer concepts.

Lisa Jackson, owner of Pie Bar in South Austin, said she has to be creative to keep her small business alive.

Jackson said the price of most ingredients rose since June 2021. The eggs and heavy cream she uses have seen 221% and 47% increases, respectively.

Despite these upsurges, Pie Bar has not raised its in-store prices. Instead, Pie Bar has relied on strategic financial moves to save where it can to maximize its profit margin, such as cutting back on staff and selling bottled water during the hot summer months.

“We kept them at $1 for a bottle of water, and we sold the heck out of it,” she said.

Jackson said a huge part of her decision to not raise prices is to maintain the community she’s cultivated at Pie Bar, citing the man who comes in for a cup of coffee before his physical therapy appointment and the parents who treat their kids to a slice of pie when they receive a good report card.

“I feel like it’s really important to be part of the community that you’re in business with,” she said.

Fried said his restaurant did not start turning a profit until three months ago—almost five years into its operation—but he chose to maintain prices and a traditional customer service model to ensure the best hospitality experience.

To Fried, hospitality is one of the main purposes of restaurant ownership. When he had a panic attack for the first time in his life eight years ago, the first thing he did was go to Uchiko.

Fried sat next to two strangers and ate with them for three hours. When he left, he felt he overcame his worries and made two new friends, whom he still is friends with to this day.

Fried said that experience made him realize the importance of restaurants bringing people together.

“The hospitality is the touchy feely part. That’s how you make the customer feel, and when you don’t have that touching point, I think it’s more difficult, almost impossible to create that hospitality,” Fried said.

The Austinite perspective

Austin resident Charles Runnels said he feels how the changing dining atmosphere is leading to a disconnect, pointing to bars and restaurants with a pickup counter.

“You’re with your friends and you’re hanging out, and then you have to get up [to get your drinks] and stop the conversation,” he said. “It’s like you have to buy three drinks at a time.”

Jake Pavlicek said he does not mind the shift.

“When I go out to eat, I like the food,” he said. “I see no difference except less effort on the restaurant’s end.”

When it comes to prices, Austinine Monica Pizanie said she does not mind paying for food that is difficult to make at home, such as sushi, but has noticed a trend of paying nearly $18 for grilled vegetables.

The state of prices and service in Austin restaurants leads some to fear what the landscape will look like in the future.

“People used to think of Austin as a city that was friendly to the mom-and-pop shops and local businesses. And it just hasn’t been that way for years. And I don’t know what the solution is. Because I think that train has left the station, and it’s not coming back,” Collins said.