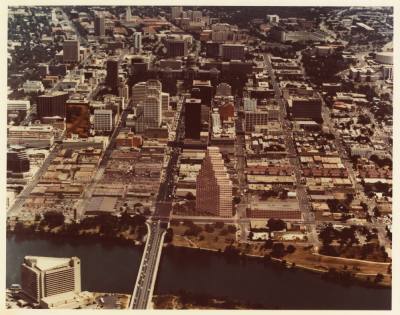

As Austin’s core is moving further from its mid-1900’s low-rise profile to prominent high-rises and high-profile buildings, some officials and preservation advocates say Austin will not be able to recoup the historic character.

Some of Austin’s land-use and preservation policies have set the stage for the widespread redevelopment underway downtown. While the Historic Landmark Commission reviews properties on a case-by-case basis and can recommend their preservation, many redevelopments still move through City Council, especially if the property owner opposes historic designation. Because leaders chose not to designate historical districts, the trend of redevelopment has already been set, some experts said.

Areas such as the Rainey Street Historic District, a nationally recognized residential block that quickly became a hub of luxury condo and hotel towers, exemplify how quickly Austin blocks are changing.

“[People] want to see something with Austin’s character and soul,” said Lindsey Derrington, executive director of Preservation Austin, a nonprofit focused on the conservation of historic areas and structures. “And where you tip the scales of, all of a sudden, more is new than old, you’re really going to change that dynamic.”

Building up downtown

Even with all the recent development, cranes still dot the downtown skyline as dozens of new tower projects are in the works—including 98 Red River St., which at 74 stories would be Austin’s tallest.

“Looking at what we know is in the pipeline, the vertical development downtown will essentially double the size of downtown,” said Dewitt Peart, president and CEO of the Downtown Austin Alliance, an advocacy group focused on downtown.

The types of developments coming to Austin also make the market stand out among growing cities, Peart said. Many towers on the horizon are not dedicated to a single use with some mix of office, residential, and hotel or retail space. Resident and corporate demand for mixed-use options could lead to downtown Austin becoming an “18-hour city” where personal and work activities take place just a small distance apart due to new development options, Peart said.

Chad Barrett, managing principal at Aquila Commercial, said today’s vertical swell builds on initial changes dating to the mid-2000s when downtown had a more “sleepy” vibe. Signature development has since moved either to the central business district or north to The Domain, in part given tech’s hold over development trends.

“Nowadays, your big tenants are the Facebooks, the Googles, now TikTok and Cirrus Logic. Those are the tenants that are really driving the growth of downtown,” he said.

Much of that new growth comes partially at the expense of what came before, an issue that can prove to be divisive both for specific projects and in the broader context of Austin’s growth.

District 9 Council Member Kathie Tovo, who represents downtown, said she embraces much of the change the city has seen over her term in office. However, she said she has also aimed for years to improve local preservation systems as older offices, homes, warehouses and restaurants are torn down to pave the way for new towers.

“There are huge benefits to the redevelopment we’ve seen downtown,” Tovo said. “I do wish ... we approached redevelopment with more creativity and that we didn’t make demolitions so very easy in this city.”

Preservation in focus

Some downtown stakeholders have held for years that Austin’s protections for other historic buildings are lacking. Advocates say the absence of effective tools leaves the city without many options to protect historic spaces.

“This economic wave has risen so high that even very well-supported and very loved—and you would think off-the-table—institutions are feeling the exact same pressure,” said Ben Heimsath, vice chair of the Historic Landmark Commission, during a March meeting.

The commission is tasked with determining the potential historic value of structures citywide. But even if the board attempts to designate a building as historic, contested demolition cases can be elevated to City Council. At that stage, Tovo said officials’ backing of a preservation tag over a property owner’s wishes happens “extraordinarily rarely” given deference to owners—while allowances for towering high-rises more often get a green light.

The conflict between old buildings and new growth recently generated a large public response related to plans to rebuild a portion of West Fourth Street, home to Austin’s LGBTQ nightlife scene. Development of a new tower would result in the demolition of several bars tied to the gay community, and an outpouring against the project led the commission to designate the properties as historic—although the move may only temporarily stop the project ahead of council review.

The Hanover Co. project team said its plans would preserve aspects of the block by bringing back Oilcan Harry’s and reconstructed brick facades. That type of middle ground is something Tovo also said she hopes city policy could better provide.

History and new growth

The case, and others recently considered by the commission, also served as an example of the varying pressures that often lead to the loss of older, potentially historic structures without significant pushback.“It’s frustrating how the few tools that we do have are being overwhelmed,” Heimsath said May 4. “This is going to be our future over the next several years, and it’s going to be pretty dismal.”

While the West Fourth Street project generated enough support for a delay, many older buildings downtown have not. One example, a warehouse building at 301 San Jacinto Blvd. now home to Vince Young Steakhouse, was recommended for historic zoning by the city’s preservation office this year. Despite its links to old Austin industry, its property owner’s wish to likely move toward more profitable redevelopment led city officials to avoid imposing a historic tag, which could limit development options.

As it currently stands, the preservation issue is typically addressed in Austin on a case-by-case basis. Derrington said the city fell behind on an effort to designate more historic districts, rather than lone properties, that could have stabilized more historic areas.

“We just started late, and so we missed a lot of opportunities,” she said.

The lack of an official designation covering Austin’s Warehouse District has led to multiple demolitions or project proposals there, one of the areas highlighted by Tovo and Derrington. But even nationally listed districts along Rainey Street and East Sixth Street are not immune. A new proposal from the owner of many Sixth properties east of Brazos Street could see modern offices stacked atop those landmark buildings in the near future.

“Over the next 10 years ... there’s going to be an immense amount of construction going on,” Peart said. “We do have challenges with infrastructure and affordability that are constantly needing to be worked on.”