Texas is experiencing its second-driest year in 128 years, which affects 23.9 million people across the state, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System.

Many of the suburban cities along the I-35 North corridor as well as San Antonio itself get a percentage of their water from the Edwards Aquifer, which has seen water levels significantly drop—down to levels not seen since 2014.

Cities across the Northeast San Antonio Metrocom and Central Texas may see increased water restrictions in the future as the drought worsens across South Central Texas due to a lack of rainfall and high temperatures, according to the National Weather Service.

The San Antonio-area, which includes the cities in the Northeast Metrocom, received 2.1 inches of rain in August and another 0.92 inches of rain as of Sept. 6, bringing to total 8.14 inches of rain so far this year, which is over 13 inches below the normal average, National Weather Service Meteorologist Jason Runyen said.

On Sept. 1, the National Drought Mitigation Center reported that nearly all of South Central Texas—90.5%—has been designated at some level of drought with abnormally dry, D0, being the lowest level and exceptional, D4, drought being the highest level.

So far, 5.3% of Texas is in D4, compared to the 71.3% of South Central Texas that experienced D4 conditions in November 2011, the last time the state experienced this level of drought.

The Edwards Aquifer Authority remains in Stage 3 of its critical period management plan—more commonly thought of as water restrictions—which requires anyone permitted to pump water to reduce their usage by 35%. Since late July, the EAA has been teetering toward Stage 4 restrictions, which requires a 40% reduction in permitted pumping levels, officials said.

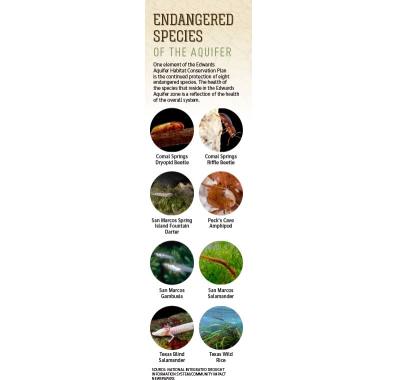

More than 2.5 million people, eight endangered species and several more on the threatened list, and other animals depend on the water from Edwards Aquifer, which has been identified as one of the largest and most unique aquifers in the world by the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department.

The J-17 Index Well in Bexar County is used to monitor and track water levels in the aquifer and correlates closely to flow levels from Comal Springs. The J-17 Index Well is over 23 feet below the historic average values for the summer months in the region, according to the Edwards Aquifer Authority.

It would take a significant amount of rain in the northwest region of Central Texas to allow drought restrictions to be lifted. If the area does not have any rainy seasons leading up to next summer, a dry climate will continue, according to EAA General Manager Roland Ruiz.

“Short of significant rainfall between now and the start of next year, we’re going to find ourselves where we are today, except earlier in the year,” Ruiz said. “Because we may not come out of any stage of critical period if we don’t have rainfall.”

Varying water supplies

While San Antonio and much of Bexar County rely heavily on the Edwards Aquifer, smaller cities in the Northeast San Antonio Metrocom each handle water differently and pump water for their residents from a variety of sources, including the Carrizo, Trinity and Wilcox aquifers.

Schertz has a partnership with Seguin to provide water through the Schertz Seguin Local Government Corporation to residents with much of the water coming from the Wilcox Aquifer.

Schertz Public Works Director Suzanne Williams said the drought is not having a significant effect on residents, and there are no water restrictions.

“We supplement with Edwards Aquifer [water],” Williams said. “I guess we look at Edwards Aquifer as a backup for Schertz.”

Williams said the city also has a relationship with the San Antonio Water System, and if they needed additional water they could get it for an additional cost.

The city has seen explosive growth in recent years, but so far, the water supply has been able to keep up, Williams said.

However, Schertz Director of Public Affairs Linda Klepper said residents may not have any restrictions right now, but the city is encouraging them to be aware of the drought and mindful of their water usage. Residents are being reminded on social media to conserve and to avoid wasteful watering, she said.

Residents of Selma also have no water restrictions, but San Antonio as well as Garden Ridge, Cibolo and Universal City are all operating under Stage 2 restrictions, which limits use of an irrigation system or sprinkler to once per week on a designated day by address between 7-11 a.m. and 7-11 p.m.

The San Antonio Water System, which provides water for most of Bexar County, has remained in Stage 2 restrictions since April and attributes its ability to avoid stricter watering rules for its customers to its greater water diversity, citing that only about 50% of its water comes from the Edwards Aquifer, SAWS water conservation director Karen Guz said.

The other 50% comes from a mix of the Vista Ridge pipeline, the Trinity Aquifer, Canyon Lake, the Carrizo Aquifer, and even recycled and stored water, Guz said.

Most of Universal City’s water comes from the Edwards Aquifer—about 3,747 acre-feet—and another 800 acre-feet is available from the Carrizo Aquifer, said Randy Luensmann, Universal City director of public works.

“So that is our drought water,” Luensmann said. “I only pump from the Carrizo in extreme drought.”

Luensmann said if the EAA were to move to Stage 4, that would mean a 40% reduction for Universal City’s annual allocation of water, which right now serves 6,600 connections.

“Right now, we are calculating and doing projections to make sure we have adequate water through the end of the year. It’s calculated by the number of days,” Luensmann said. “We’ve done our projects, and we’re still in good shape.”

The drought would have to be more severe for the city to require greater restrictions from its residents, he said.

“We don’t want to ban outdoor watering, and that’s what the next stage would be,” Luensmann said.

While rain is needed across the region, to have a positive effect on the Northeast Metrocom cities, it would need to fall in a certain area of the Edwards Aquifer, he said.

“If it’s over the Edwards that’s where we want [rain] to go—over the recharge zone,” Luensmann said. “Every drop [helps]; really, it’s a flood that gets us out of drought. You hate to say that.”

Luensmann pointed to droughts in 1998 and 2002, when significant flooding was what ended the droughts.

“I’m anticipating history repeats itself and that we get more rain,” he said. “I think we’re going to get more soaking rain.”

Water conservation plans

During the second half of August, the Northeast Metrocom area and pockets around San Antonio received scattered rain just as the Edwards Aquifer Authority was preparing to declare Stage 4 of its Critical Period Management Plan to enforce permit reductions to the region.

The plan is put in place to help sustain aquifer and springflow levels during times of drought by temporarily reducing the authorized withdrawal amounts of Edwards Aquifer permit holders, which includes utility companies.

In Stage 4 of the plan, permit holders in Bexar, Comal and Guadalupe counties must reduce their annual authorized pumping by 40%. In Stage 3, pumping is reduced by 35%.

Those minor rain events enabled the EAA to hold to Stage 3 restrictions, officials announced Aug. 18.

Chad Norris—deputy executive manager of environmental science for the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority Canyon Reservoir and Trinity Aquifer, as well as a member of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan Science Committee—said when drought conditions are persistent or spring flows reach a lower output, certain measures of the conservation plan are implemented.

“Some of those measures involve using alternative water sources, reducing reliance on the [Edwards Aquifer] itself,” Norris said. “And those are all designed to maintain spring flows and make sure that they don’t get below a threshold that we have identified as needed to reduce the impacts to [aquatic] species.”

Norris said he expects some of the bigger impacts of the drought to be in the smaller tributaries in Texas that do not have springs to provide base flows.

“We have plans like the Edwards Aquifer HCP. Water providers have drought contingency plans; municipalities and others have drought measures that they take to reduce water use,” Norris said. “I feel like, in general, we are prepared and not unaccustomed to droughts like we’re experiencing now. But with every drought, you’re always just waiting for the next rainfall.”

Habitat conservation plan

The negative effects of the ongoing drought are not limited to water suppliers and municipalities. The EAA is also responsible for managing spring flows that provide habitats for endangered and threatened species.

Habitat protection has been a part of the EAA’s mission since its inception. The creation of the EAA was part of Texas law put in place after the Sierra Club filed suit in 1991 against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “citing negligence to provide the necessary protection required by the Endangered Species Act.”

Today, the EAA uses the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan—which was first approved by the USFWS in 2013—to govern how the authority will protect those species that live in the Edwards Aquifer a well as the Comal and San Marcos springs that are federally listed as endangered and threatened, said Scott Storment, executive director for the EAA Threatened and Endangered Species Department and the program manager for the EAHCP.

There are seven endangered species and one threatened species on the list, he said.

With the conservation plan, the USFWS also issued a 15-year Incidental Take Permit that provides authorization to those entities that hold permits under the Endangered Species Act to pump an approved amount of water from the aquifer, Storment said.

Permittees include the EAA and the cities of San Marcos, New Braunfels and San Antonio through the San Antonio Water System as well as Texas State University. That 15-year permit is set to expire in 2028, he said.

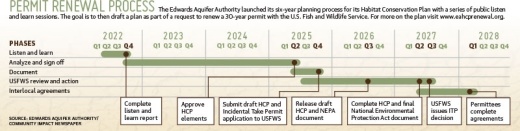

The EAHCP, through its committees, began in August an extensive five-year process leading up to the renewal application due in 2028. They began with a series of listen and learn sessions to involve stakeholders and the public, Storment said.

Ideally, the new application will be for a 30-year permit, he said, but that has yet to be determined and is affected by things that are still unknown.

“Climate change is a big factor,” he said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty and vulnerability of what is going to happen in that 30 years. We’re taking it very seriously and undergoing intense modeling. It’s all linked together.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly listed the number of endangered and threatened species that live in the Edwards Aquifer area. It has been corrected.