The shelters share similarities in how they define what stray means—an animal running free or at large, with no physical or verbal restraint—and in some cities, the definition includes that there appears to be no known owner.

According to animal care experts, facilities across the region—including in Schertz and Cibolo—see hundreds of animal intakes over the course of a few months.

Each facility handles issues related to strays, including treatment for diseases, spay and neuter procedures, educating pet owners, and other initiatives to reduce the number of animals being cared for in shelters.

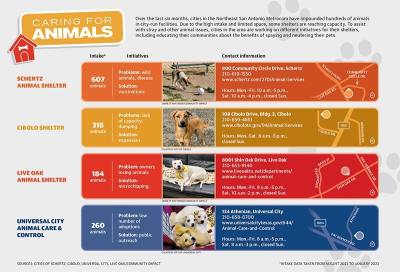

In Schertz, from August 2022 through January 2023, the Schertz Animal Shelter took in 607 animals, mostly cats and dogs, Schertz Animal Services Manager Megan Lagunas said.

In Cibolo, from August 2022 through January 2023, the Cibolo Animal Shelter took in 318 animals. Of those intakes, 229 were dogs, and 89 were cats, Cibolo Animal Services Manager Jacob Jenkins said.

By comparison, in that same time frame, the city of San Antonio Animal Care Services department took in 12,856 animals, including returns from foster care and adoption as well as rescues, according to an annual report. Of that total, 8,499 were stray animals.

Lagunas said many of the animals in the shelter are from unwanted litters from animals that were not spayed or neutered, animals that escaped their homes or yards, abandoned pets, and wild intake.

“People have unwanted litters, and they don’t know what to do with them, so they show up to the shelter,” Lagunas said. “I think that is the main source of the stray population in this region of Texas.”

Identifying the problems

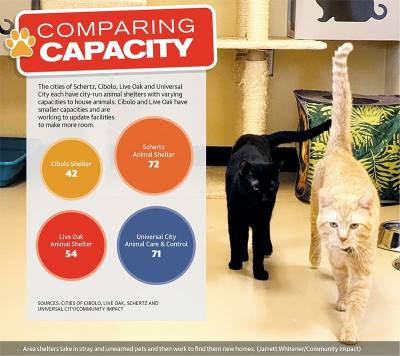

In the Northeast San Antonio Metrocom, the cities of Schertz, Cibolo, Universal City and Live Oak each have shelters where residents can adopt pets.

In Live Oak, the shelter has capacity for about 24 dogs and up to 30 cats. Animal Control Supervisor Stephanie Kinney said the Live Oak shelter has impounded 184 animals since August with most being pets from area homes.

“[An animal] is always a pet that gets put into the shelter, but it is a question of if it is a pet that is cared for, or is it a pet that people do not really care about, and that is what we get stuck with,” Kinney said.

Similar to Live Oak, the Universal City shelter returns many pets to owners. Those that are unclaimed are then assessed for adoption.

While Universal City does not have issues with being overcapacity, the shelter does assist surrounding shelters with animal transfers when those shelters cannot take in any more pets.

In Schertz, the shelter has 72 kennels, including the quarantine and isolation kennels. Over the last six months, the shelter has brought in 607 domestic and wild animals.

While the Schertz facility also does not have issues with capacity, impounded animals frequently have diseases or illnesses that need to be treated, Lagunas said.

“On a daily basis, we have disease in our shelter,” she said. “It is contained, but almost every single animal that comes in here has something, whether it is worms or a skin disorder or anything.”

With Schertz and Cibolo being larger than surrounding cities and having more rural areas, there is an increased number of animals that are dumped as people do not know what to do with their animals, Cibolo Animal Services Manager Jacob Jenkins said.

“We have a lot of [dumping] because we only have 12 kennels and cannot take owner surrenders at this time, but we do try to offer different solutions to these owners and reach out to different organizations to try and rehome these pets,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins said the Cibolo facility was built in 2000, when the city had a population of about 2,000 people. With a growing population of around 38,000, the 12-kennel facility is consistently full with no room for extra dogs.

When the kennels are overcapacity and pet owners want to surrender animals, the shelter workers contact other area shelters, including in Universal City and Schertz, to see who has space.

“Right now, I have 16 dogs with only 12 kennels, so I have to get creative,” Jenkins said.

Cibolo Police Lt. Jan Wilkiewicz said many of the dumped animals are due to residents encountering hardships and not knowing where to go to get help with an animal they can no longer care for.

When shelters are at or nearing capacity, it can be more difficult for owners to hand over pets, which leads to areas such as Cibolo Creek being used as dumping grounds.

“Just because people are making poor choices does not make them bad people,” he said.

Finding solutions

To address the problem of strays, city officials are working to expand facilities and help educate the public on responsible animal care and pet ownership.

Cibolo has the smallest facility and is in the exploratory phase of coming up with a plan to invest in and expand the shelter and animal operations.

While discussions are still preliminary, there is a desire in the community to make more room in the shelter, Jenkins said.

Another initiative for the city is to help educate the community on alternative resources for rehoming pets, which would cut down on the number of animals dumped in the more rural areas.

Officials are also working to better enforce penalties for dumping, to ensure those who abandon animals are properly fined, Jenkins said.

Live Oak officials are working to upgrade kennel gates to transition quarantine zones into adoptable zones, which will increase the number of animals the shelter can hold.

Kinney said there is a discussion about building a new facility, but those conversations have not moved forward.

Kinney said officials are also working to revise city ordinances to help eliminate the issue of not being able to return animals to their owners.

Revised ordinances will enable the city to microchip an animal to ensure the owners are easily reachable should the animal go missing again.

“After the first impound, when your dog gets out, we are going to microchip that animal,” she said. “That way, if we get it again, it is that much faster to get ahold of the owner.”

Live Oak officials also use social media, such as Facebook and TikTok, to promote animals in the shelter, which has led to an increase in adoptions, Kinney said.

“We go as far as doing collages for every animal that we have, and we go as far as doing TikTok videos for them,” she said, adding it has been an effective strategy as animals are being adopted more quickly.

Over the last couple of years, Schertz has invested $650,000 in the shelter and worked to address holding space, building infrastructure and heating and cooling, which has alleviated some of the capacity difficulties.

However, city officials continue to work on the shelter with the goal of adding an outdoor cat space and an agility course for dogs in the future, Lagunas said.

The main initiative for Schertz is to educate residents about vaccinations and preventive measures for diseases and illnesses.

Lagunas said the city relies on a passionate team of volunteers and staff to collect the animals and care for them.

“It is a hard job sometimes, but everybody is passionate about it,” she said.

Community involvement

Each shelter relies on assistance from the community with each in need of volunteers and donations.

For Schertz, the shelter relies on the community to help with vaccinations and ensure pets are properly secured outdoors.

“We want to discuss rabies a lot with the community and help educate about responsible pet vaccinations,” Lagunas said. “The rabies vaccine is so important. ... The core of our existence is to prevent the spread of rabies and zoonotic disease.”

Area cities host events for discounted vaccinations, microchipping, and spay and neuter services.

Schertz offers residents microchipping for $15, which is about $45 cheaper than other facilities.

Similar to Live Oak, if an animal is impounded without a microchip, then it will be chipped before leaving the facility.

In Universal City, the shelter has initiatives to provide low-cost microchipping and vaccinations in conjunction with Penny Paws twice a month.

Wilkiewicz said shelters such as the one in Cibolo rely on community support to succeed, and without monetary donations and volunteers, the facilities would not be able to continue helping pets and other animals in the area.

“We wouldn’t survive without the support of the community,” Wilkiewicz said. “I have gratitude for the community and the feedback they give us and the continued support going forward. We are a small shelter, but we are holding our own.”