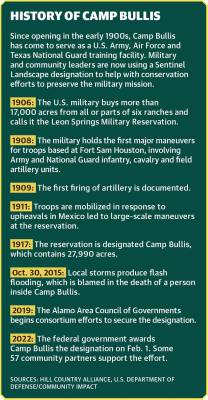

For more than 100 years, the U.S. Air Force’s Camp Bullis on San Antonio’s north side has been home to military training operations that took advantage of its more rural location.

Over time, homes, businesses and a booming population began to encroach on the camp and put at risk the military’s ability to succeed at its mission: effectively training today’s men and women who serve.

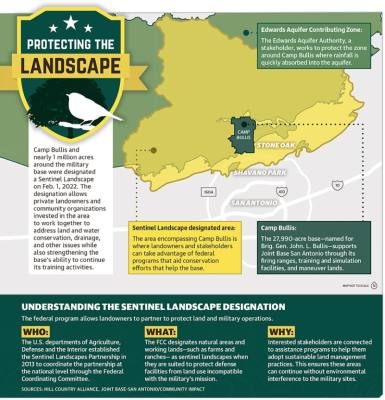

Now with the help of the Sentinel Landscape designation, efforts are underway to help area landowners preserve nearly 1 million acres around the camp, protect water and wildlife, and reduce noise and light pollution.

“The challenge is how do we work across this vast landscape to aggregate all of the various technical and natural resources in a way that supports landowners around Camp Bullis and supports the training mission,” said Daniel Oppenheimer, land program director with the Dripping Springs-based nonprofit Hill Country Alliance. “A lot of that comes back to protecting water, soil health through conservation, enhancing groundwater—those things will help to mitigate flash floods as well.”

Conservation and preservation

Camp Bullis is part of the Greater Joint Base San Antonio operations and supports training of military members who serve at any of San Antonio’s bases, including the north side’s JBSA-Randolph.

The 27,990-acre military site houses state-of-the-art training and simulation equipment, firing ranges surrounded by open skies not clouded by light pollution, and an abundance of land for training maneuvers that are not affected by noise pollution.

On Feb. 1, 2022, the federal government designated Camp Bullis and nearly 1 million acres around it a Sentinel Landscape.

Securing this designation enables stakeholders—such as private landowners and conservation organizations—to leverage federal and state monies to fund initiatives to help meet five overarching goals, said Oppenheimer, who is coordinating communications and the efforts of 57 private- and public-sector groups that support conservation efforts and Camp Bullis.

Those goals include promoting responsible development and land stewardship; maintaining and improving agricultural productivity, such as farming; addressing climate-related challenges, such as drought, flash flooding and wildfire risks; preserving and enhancing habitats to aid in the recovery of native and threatened wildlife species, including the golden-cheeked warbler; and supporting and expanding recreation opportunities, such as parks and trails.

All the stakeholders aim to work together to conserve natural resources within the area and reduce risks that are the byproducts of development, such as light pollution and drainage runoff, Oppenheimer said.

Such efforts will benefit surrounding properties, communities and ecosystems and strengthen military readiness at Camp Bullis, which is important because JBSA’s military activities contribute $31 billion yearly to Texas’ economy, Oppenheimer said.

“If we want to have any success here to enhance natural resources through conservation, that means working with private landowners in a way that supports their goals, values and needs,” he said. “We also have an opportunity to engage developers and promote thoughtful practices that help us to steward natural resources.”

Earning the designation

In early 2019, the Alamo Area Council of Governments, a San Antonio-based voluntary association of local governments and organizations, began spearheading a consortium to help safeguard Camp Bullis’ military mission.

The group’s goal was to secure the Sentinel Landscape designation with community stakeholder support, which would in turn open the door to federal programs and financial support.

AACOG Executive Director Diane Rath said when the group discovered the Sentinel Landscape program, officials realized it could be valuable in reinforcing Camp Bullis’ military activities.

“This is a unique program as it has support from the military, conservationists and developers because it is voluntary and nonregulatory,” Rath said.

Camp Bullis was the first Texas defense facility to receive a Sentinel Landscape designation, which covers nine other military sites nationwide.

Local military leaders voiced support for the Sentinel Landscape designation. Army Brig. Gen. Russell Driggers, commander of JBSA and the 502nd Air Base Wing, said he appreciated those working to ensure Camp Bullis remains a reliable military training ground.

“Thanks to the designation and the efforts of our partners, more resources will be available to willing landowners to help ensure military training operations can continue unimpeded,” Driggers said.

Partnering with landowners, developers

Oppenheimer said Sentinel Landscape partners aim to identify the amount of money invested in agricultural productivity and natural resource conservation in the designated area as well as acreage enrolled in programs that help property owners with land stewardship efforts.

Oppenheimer said this could include better animal grazing practices and soil health and infiltration; reducing erosion; and conservation easements, which are voluntary, legal pacts that permanently limit uses on a certain amount of land.

Camp Bullis’ partners secured $5.1 million from one such funding source, the Defense Department’s Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration program, which helps local landowners with mutually beneficial land management practices and the implementation of conservation easements, Oppenheimer said.

Separately, community partner Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute secured $8.5 million through the Agriculture Department’s Regional Conservation Partnership program, which Oppenheimer said will further help local landowners with conservation.

“Farmers and ranchers make good neighbors to a military installation, helping safeguard the best training environments for our men and women in uniform,” said Roel Lopez, Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute director.

Gilbert Gonzalez, CEO of the San Antonio Board of Realtors, said the Sentinel Landscape’s focus on compatible land use around Camp Bullis will boost voluntary landowner cooperation toward efficient development.

“The Sentinel Landscape program is designed to complement residential real estate development and create natural amenities such as parks and open spaces that enhance the overall real estate value of the landscape,” Gonzalez said.

Being water wise

Oppenheimer said to counter byproducts of increasing land development around Camp Bullis, protecting groundwater sources and water supplies, and addressing drainage runoff and flood risks in and around the training facility is vital.

Shaun Donovan, environmental sciences manager with the San Antonio River Authority, said Camp Bullis is prone to flash flooding due to the post’s proximity to the Salado Creek and Cibolo Creek watersheds, and it sits on the edge of the Edwards Aquifer contributing zone, where rainfall penetrates the land surface.

The river authority is collecting public input to update area flood plain maps, which will require Federal Emergency Management Agency approval and will take affect within two years. Donovan said new maps may help to produce flood mitigation methods.

Flash flooding has swept away vehicles; inundated roads; and, in at least one case, caused a death at the post, JBSA officials said.

Donovan said new area flood plain maps will be based on a higher frequency of severe rainfalls with “more significant storm impacts.”

“We want Camp Bullis to have a long-term ability to stay a safe training facility,” Donovan said.

Oppenheimer said area water organizations may help to further protect and replenish surface and groundwater water sources in concert with other stakeholders and holders of water rights.

“Camp Bullis, like the rest of us, relies on groundwater and the Edwards Aquifer beneath our feet for drinking water,” Oppenheimer said.

Aiding wildlife, dark skies

Stakeholders also seek to fortify dark-sky programs and policies designed to help communities conserve energy, improve human health, and reduce artificial light’s effects on activities at Camp Bullis and in nature, said Britt Coleman, president of the Bexar Audubon Society, a nonprofit and area stakeholder that works to protect bird and other wildlife habitats.

“If [Camp Bullis gets] too much light pollution, it ruins their night training abilities,” Coleman said.

Coleman said he, other local environmentalists and some residents of the north side Cibolo Canyons neighborhood are worried that potential new nearby development could indirectly affect Camp Bullis

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is mulling a request by Starwood Land Residential Development Co., the Florida-based developer of Cibolo Canyons, to swap 63 acres of protected habitat for the endangered golden-cheeked warbler with an adjacent 144 acres owned by Starwood Land.

Coleman said the 63 acres are prime, protected habitat for the golden-cheeked warbler, whereas the 144 acres are not ideal for the songbird.

“The precedent of developer-initiated land swaps on conservation easements is dangerous,” Coleman also said.

Starwood Land did not answer a request for remarks in this story.

Coleman said he hopes the federal government opens a new public comment on Starwood Land’s land-swap proposal. There is neither a timetable for a decision nor details on the company’s designs on the undeveloped land.

Doris Brown, a Cibolo Canyons resident who is helping to alert neighbors about the developer’s land swap proposal, said neighborhood residents share worries over how Starwood Land’s plans - if approved - could affect the golden-cheeked warbler’s habitat.

But Brown also said the proposal feels like a bait-and-switch tactic.

“People who built their home here were told nothing would ever be built on that [undeveloped] land,” Brown said.

But Coleman said a land swap could disrupt the warbler habitat near Cibolo Canyons and force surviving birds toward 7,000 acres of warbler habitat at Camp Bullis.

“When we think of Camp Bullis, we can’t think of the camp as an island, but rather all of the communities tied together with the military installation,” he said.