For example, Pflugerville ISD, which is located near Austin, lost roughly $1 million during the last 12 weeks of the 2021-22 school year, officials said.

The district serves about 25,000 students, but due to gaps in attendance, it only received funding for 23,000 students, according to district chief communications officer Tamra Spence. These gaps were primarily fueled by COVID-19 cases and students who participated in classes remotely.

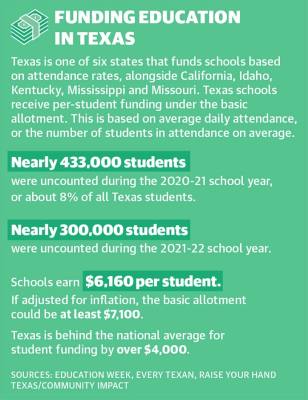

Because Texas public schools are financed based on attendance rates, many districts across the state faced similar issues.

Students who miss school aren't counted

Schools receive per-student funding under the basic allotment. This is based on average daily attendance, or the number of students in attendance on average.

Average daily attendance is calculated by finding the sum of attendance counts throughout the school year and dividing that by the number of days that schools are required to be open, according to the Texas Education Agency.

Schools then earn $6,160 per student who meets the average daily attendance threshold.

If a student is absent, they are not counted for the day. For funding purposes, students who are frequently absent are not counted at all, according to the TEA.

But day-to-day school operations do not change when students are absent, officials said.

“We don’t pay teachers based on the number of kids or percentage of kids who come to school for a day; teachers don’t prepare lessons assuming that only 92% of the kids are going to be there,” said Jennifer Land, Pflugerville ISD's chief financial officer. “We still have to prepare and fund and act as though we’re going to have 100% of our students at school every day.”

Land also serves as the board president for the Texas Association of School Business Officials, a nonprofit organization that supports public school officials.

Nearly 300,000 students were uncounted during the 2021-22 school year, according to policy nonprofit Every Texan. Roughly 433,000 were uncounted during the 2020-21 school year—that's 8% of all students in Texas.

“Schools do not save money when children are absent,” according to a report by Chandra Kring Villanueva, Every Texan’s director of policy and advocacy. “In fact, chronic absenteeism brings additional costs, such as remediation for students and administrative time for teachers and districts.”

Meanwhile, Texas is behind the national average for student funding by over $4,000, according to research by Education Week. The basic allotment also is not adjusted for inflation. With inflationary adjustments, the basic allotment should reach at least $7,100, according to Raise Your Hand Texas, a public policy organization focused on public education.

School districts also receive funding from local property tax rates. Bob Popinski, the senior director of policy for RYHT, said lawmakers need to continue to invest in public schools, even when property taxes increase.

Last biennium, the state saved about $5 billion due to property tax hikes. Popinski said that money was used to fund other programs across Texas.

“A big chunk of it did not go back into public education,” Popinski said. “[And] our contention is that any kind of savings to the state due to local [property] value increases needs to be pumped back into public education through increases in the basic allotment or funding for other public education programs.”

State responds to gaps in attendance

During the first year of the pandemic, the TEA funded schools based on attendance and enrollment estimates made before the pandemic. As districts began to shift to more in-person instruction during the 2021-22 school year, officials issued an operational minutes adjustment, which excluded periods with low attendance rates from districts’ averages.

However, the adjustment was only in effect for the first two-thirds of the school year. During the latter portion of the year, average daily attendance rates were calculated normally.

The TEA reported that schools were not held harmless for enrollment declines last school year.

After the operational minutes adjustment ended, Pflugerville ISD’s attendance rates hovered around 92%. The district missed out on approximately $1 million during the last 12 weeks of the 2021-22 school year, Land said.

Attendance rates are currently around 94%, a 4 percentage-point decrease from pre-pandemic levels. Land said she thinks this is the new normal, because parents and administrators are more aware of viral illnesses and the importance of increased caution to keep students healthy.

Dr. Brian Woods, the superintendent for San Antonio's Northside ISD, said officials should not have terminated the operational minutes adjustment. In fact, he thinks it should still be in effect.

“I think that some folks in state government pretend that COVID has just gone away and that the problem no longer exists in schools, and that's just false,” Woods said. “Granted, it’s not anything like it was in [January] of last year, at the moment, but that doesn't mean that it's eradicated.”

Woods said his district still struggles with attendance rates, especially during flu season.

In Grapevine-Colleyville ISD, which is located near Dallas-Fort Worth, administrators are working to boost attendance by promoting in-school learning and connection among students.

Tamara Morris, the district’s director of student engagement, said the sense of community waned when classes were pushed online.

“We are trying to get ourselves back to the idea that we're better together,” Morris said. “We need to be in the building [to] learn and grow, and get ourselves ready for college, career and military readiness.”

The campaign focuses on celebrating students, teachers and parents for the effort they put into each school day.

Attendance in Grapevine-Colleyville ISD is about 96%, which chief financial officer DaiAnn Mooney said is equivalent to prepandemic rates. Last school year, attendance was about 94.8%.

A push for enrollment-based funding

Texas is one of just six states that funds schools based on attendance rates, alongside California, Idaho, Kentucky, Mississippi and Missouri.

According to Every Texan, there are four methods commonly used to fund schools based on enrollment: average daily membership, single count days, enrollment periods and multiday counts.

The most common method, average daily membership, is used in 23 states. Villanueva said it is similar to Texas’ existing funding model. In this case, enrollment is recorded throughout the year and used to determine district-by-district funding.

Two bills in favor of enrollment-based funding—Senate Bill 728 and House Bill 1246—were filed during the 87th Texas Legislature, which occurred in 2021. But despite support from bipartisan lawmakers and educators across the state, neither bill received a hearing or reached the chamber floors.

Enrollment-based funding would help protect schools from emergency situations, such as natural disasters or another pandemic, Woods said.

“There are just so many [emergency] situations that impact attendance, and it really creates a very unstable environment for schools,” Woods said. “And in my mind, it's past time to reconsider that [funding] model.”

The 88th Texas Legislature begins in January.