By 2025, the Fort Bend Subsidence District is requiring the northeastern half of Fort Bend County—including the city of Sugar Land—to reduce groundwater reliance from 70 percent to 40 percent of the overall water supply, resulting in an increase to residential water bills.

“This is a regulatory requirement, and there’s not an option to do nothing,” said Katie Clayton, Sugar Land water resources manager, during a March 19 City Council meeting.

Groundwater is found underground in pores and fractures between sand, gravel and other rock materials. However, pulling too much groundwater can lead to subsidence—the gradual sinking of land—and the FBSD has regulations in place to minimize this effect.

“The groundwater withdrawal from the aquifer causes compaction in the aquifer, and we see that as subsidence on the surface,” FBSD General Manager Mike Turco said. “By curtailing the amount of groundwater used, we can stabilize the aquifer levels and prevent subsidence from occurring in the future.”

In response to these requirements, Sugar Land city staff has been working with consultants, residents and City Council to form its Integrated Water Resource Plan, which was approved by council during the March 19 meeting. Some alternative water sources include surface water resources found in bodies of water such as rivers, creeks and reservoirs.

Through diversified water resources, Sugar Land’s plan will supply the city with the additional 6 million gallons of water that will be needed per day for average, nondrought weather conditions by 2025—when the FBSD regulations will be in effect.

“[Subsidence] can create potential flooding issues, and parts of Houston have seen significant problems,” Clayton said. “Fort Bend is trying to learn from those mistakes, and the subsidence district was created to minimize that land subsidence, and they do that through regulation of our groundwater supplies.”

Limiting reliance on groundwater

The most subsidence has occurred in Harris and Galveston counties, with 10-plus feet of subsidence in some areas, Turco said. However, those counties have been developed at a larger scale for a longer period of time, resulting in more land sinking, he said.

“Fort Bend County is rapidly becoming suburban and urban in places as one of the fastest-growing counties in the country, certainly in the state of Texas,” Turco said. “All of those businesses and folks moving to Fort Bend County require water and groundwater development.”

Sugar Land falls in the northeastern half of the county known as Area A, which is more densely populated and therefore relies more on groundwater resources. The southwestern half of Fort Bend County—Area B—has no regulations from the subsidence district because it is sprawling with more rural land.

Subsidence in Area A ranges from 1-4 feet in the eastern portion of Fort Bend County along Hwy. 59, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, Turco said. The FBSD monitors subsidence with a GPS network throughout the county, he said.

The last time the FBSD updated its regulatory plan was in 2013, which used 2010 census data. Turco said the district will re-evaluate where regulations will be required in 2020 when updated census data becomes available.

“Certainly, there are areas in Area B that have gone through some rapid development or are about to go through rapid development that will have to be studied to see what the impact is going to be on the aquifer,” Turco said.

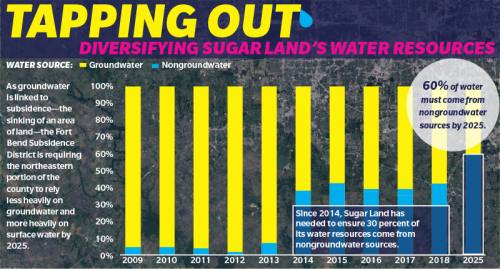

Prior to 2014, more than 90 percent of Sugar Land’s water came from groundwater resources. The FBSD, created in 1989 as a conservation and reclamation district, required in 2014 that 30 percent of water resources in Area A come from alternative sources.

The completion of the city’s surface water treatment plant in 2014 helped satisfy the 30 percent nongroundwater requirement, Clayton said.

As 2025 approaches, Sugar Land will need to double its surface water resources or face a penalty fee of $6.50 per 1,000 gallons per day. Solutions recommended by staff include expanding the surface water treatment plant to handle an additional 5.5 million gallons per day, expanding reclaimed water facilities, practicing basic conservation, implementing advanced metering infrastructure and controlling water loss.

“The implementation plan would allow us to phase these projects through time, so we would start out and ensure that the surface water expansion was online by 2025 and then be able to phase those other projects in as we see the need,” Clayton said.

The expansion of the city’s surface water treatment plant would not limit the facility from being expanded again in the future, Clayton said.

“With 1,100 people a day still coming to Texas, and we’re not making any more water anywhere, it’s going to get more expensive, and more people [will be] competing with the same resource,” District 1 City Council Member Steve Porter said during a workshop meeting in late February. “We’ve seen over the last two, three, four years that our primary supplier of surface water has raised our rates almost every year—and not by single digits.”

Based on a rough analysis of estimated monthly bill increases, residents could expect an increase of about $7.65, Clayton said.

The average Sugar Land resident uses about 7,800 gallons of water per month, resulting in a monthly water bill of $30.38, according to city data. The necessary shift away from groundwater reliance would increase resident’s monthly bills to about $38.03, Clayton said.

Tapping into available resources

Sugar Land’s IWRP included input from a citizen-led task force that ranked reliability of water resource supplies as the highest priority, and system efficiency and optimization tied as the next most-important objectives. Cost efficiency was ranked third.

“The results were interesting; it wasn’t what I expected,” said Trisha Frederick, task force chair and transportation division project manager at the Houston-based Costello Engineering and Surveying firm. “Typically, when choosing projects, it’s driven by cost, but I think this task force selected and ranked objectives that they felt were best for the community, which is a value found in the integrated planning approach.”

Frederick said advanced metering—something many energy companies use to track water usage—will help residents identify any leaks or excessive water use. Responding to alerts about where leaks are coming from can also save users money.

“It’s all about changing behavior, and that’s typically a little bit slower, but I think the metering systems—especially when it’s directly related to how much your water bill is—you would definitely be interested in receiving those alerts,” Frederick said.

It will cost Sugar Land about $90 million in the next several years to implement the plan’s projects, Clayton said.

“We’re dealing with unfunded mandates coming from these regulatory agencies,” Porter said during the February meeting. “As you know, we’ve probably already spent $100 million on the first wave. We’re looking at potentially another giant amount of money that’s unfunded from the state requiring us to meet the 60 percent.”

Sugar Land has surface water supply contracts with the Gulf Coast Water Authority and the Brazos River Authority as well as water rights on Oyster Creek, Clayton said.

During average weather conditions, the city uses about 27 million gallons of water per day with 10.7 million gallons per day coming from nongroundwater resources. By 2025, nongroundwater resources will need to be increased by about 6 million gallons per day for a total of 16.7 million gallons daily. In dry weather conditions, the city will need to come up with an additional 11 million gallons per day from nongroundwater resources, Clayton said.

The IWRP would result in an additional 9 million gallons per day in surface water resources through conservation strategies and facility expansions, according to the plan.

“I think the hybrid plan is diverse,” Frederick said. “You’re looking at expanding infrastructure. You have the water conservation piece, which pulls the community in, so I think it’s just a diverse portfolio, and if one project doesn’t work out, we still have additional projects to make the plan work.”

The FBSD does not have plans to restrict groundwater further after 2025, Turco said. However, he anticipates more regulations will be needed to sustain future growth.

“As Fort Bend County continues to grow, we’ll continue to look at these other water management strategies, including water conservation, which is an important part of all of our water management strategies as we move forward because water conservation puts not only more groundwater on the table but also more surface water on the table, too,” Turco said.