Sleeper, who was 32 years old at the time she went missing, was last seen attending a barbecue with her husband and friends off Bowler Road and FM 1488 just east of Magnolia on the evening of March 21, 2015, according to records from the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office. According to Sleeper’s husband, the family—along with Sleeper’s 3-year-old son—went home to their residence on Turtle Dove Lane in Magnolia in the early morning of March 22. After running errands, Sleeper’s husband returned home to find Sleeper, her purse and cell phone missing. Sleeper has not been seen since.

Years later, her family is still searching to find answers as the case has now grown cold.

There are at least 60 other cold cases involving missing persons or murder in Montgomery County, according to records from the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office. David Mittelman, CEO of Othram, a forensic lab in The Woodlands, said cases grow cold when there is no further evidence or leads. Police departments often have limited budgets for cold cases, and they usually rely on federal or state grants to fund the resources to investigate them.

The state also faces a backlog of DNA testing kits, including a backlog of 2,138 rape kits as of 2017, according to End The Backlog, a nationwide nonprofit focused on reforming rape kits, which could help solve cold cases.

“You send your DNA to [the state] crime lab—best-case scenario you’re looking at a matter of three, four months ... to get any kind of answer back,” Texas Ranger Robert Bess said.

Despite the roadblocks, cold cases in Montgomery County have made headway. In February, Montgomery County Forensic Services, in partnership with Othram, used DNA technology to solve a 2016 cold case regarding an unidentified man in The Woodlands. And on Feb. 2, the sheriff’s office launched a new regional public information initiative, known as Cold Case Warm Up.

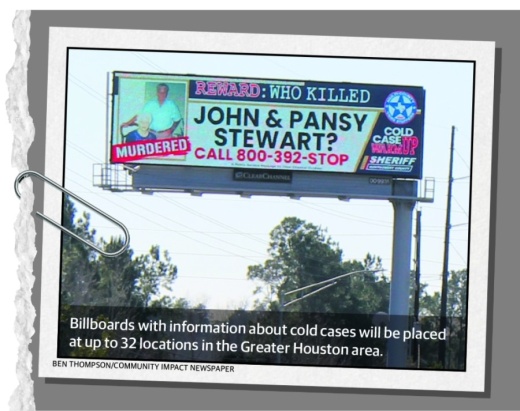

Cold cases will be featured on billboards throughout the Greater Houston area with contact details to submit tips. The first crime to be featured is the August 1995 murders of John and Pansy Stewart in Conroe.

“We would just like to see if we can find someone, somewhere that knows something about this crime,” the victims’ son John Stewart said. “We need closure.”

Looking for leads

In 2006, the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office was awarded a grant to investigate cold cases. Prior to the cold case unit formed in 2006, which is staffed by two senior detectives, detectives were not specifically assigned to cold cases, Lt. Scott Spencer said.There are nine cold cases in Magnolia and Pinehurst, according to records from the sheriff’s office. Sleeper’s case is the most recent case to grow cold in Montgomery County, according to county records.

As the county renews its efforts to tackle cold cases, the billboard campaign, which is intended to raise public awareness on select cold cases, is a partnership among the sheriff’s office, advertiser Clear Channel Outdoor and the nonprofit Multi-County Crime Stoppers. Crimes will be broadcast on 32 billboards on a quarterly basis, and cases that could benefit the most from exposure will be chosen, Spencer said. The first victims to be highlighted—John and Pansy Stewart—were found dead in their home on Foster Drive in Conroe on Aug. 15, 1995.

“We have kept this case open trying to develop leads,” Sheriff Rand Henderson said. “As the years have gone by, that has become more difficult.”

DNA technology

Reopening a cold case requires an extensive review process, said Bess, who has solved decades-old cases and once worked on a cold case in Montgomery County.“You have to look at every lab report. You have to watch videos. You have to look at pictures. You have to review autopsies,” he said. “You’re looking back through a looking glass.”

Bess said police who originally worked the case usually have done everything they could in terms of traditional police work. The key to look for is DNA evidence that has not yet been tested.

“In 1991, blood typing was what they did,” Bess said. “We do things totally different now.”

The cold case unit uses a technology known as Parabon Snapshot-DNA Phenotyping, which takes DNA from an unknown individual to predict ancestry and physical appearance traits, Spencer said.

“This is helpful in numerous types of cases, including unidentified skeletal remains and murders,” he said.

Since 2006, the unit has cracked eight cold cases: Two involved identifying skeletal remains, and six led to the identification of a suspect, according to Spencer.

Traditionally, Mittelman said forensic evidence is uploaded into the Combined DNA Index System, a national database. CODIS collects 20 markers from DNA to construct a profile, and it can be used to match persons if their DNA or a close relative’s DNA is in the system.

But Othram’s technology takes thousands of markers from DNA to reconstruct a genealogical profile that can be used to identify even distant relatives. For The Woodlands case, Othram reconstructed a genealogical profile to identify distant relatives of the deceased, which led to his identification in February.

DNA technology has also been used to solve cold cases in Harris County.

The Harris County Sheriff’s Office currently has 604 cold cases dating back to 1971, according to Homicide Unit Lt. Robert Minchew. The unit’s last cold case initiative was funded through the Solving Cold Cases with DNA federal grant from 2014-16, he said.

As a result, Minchew said the unit reviewed 144 cold cases, submitted hundreds of items of evidence for DNA processing and filed nine murder cold cases, making them no longer considered “cold.”

Due to an increase in homicides, Minchew said the county’s cold case unit staff was reduced from two full-time investigators to one part-time investigator a year ago. While there is some overtime opportunity for homicide investigators to work on cold cases, the unit has not filed a cold case since 2017.

“Last year, we had 124 murders; even though we had an 80% clearance rate, that still leaves a lot [of cases] that turned cold eventually,” he said.

Wading through a backlog

Despite recent efforts from law enforcement and the Texas Legislature, there is still a statewide DNA testing backlog, which hinders progress on cases, Bess said.“You’re talking about a lab that’s intaking hundreds, if not thousands, of cases that are being submitted yearly,” he said. “Every police department in Texas is submitting everything they have to the state crime lab.”

The Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office submits evidence to both state and private labs, depending on their capabilities, Spencer said.

Bess said he feels the state is well-positioned in terms of funding and policy, and the statewide backlog has improved in recent years. For instance, Texas has reduced its untested rape backlog kit from 18,955 in 2011 to its 2,138 as of 2017, according to End The Backlog. Texas has also enacted various laws to improve its handling of rape kits, including House Bill 8 in 2019. Under HB 8, crime labs must test kits within 90 days, and agencies are prohibited from destroying rape kits related to a case that has sat unsolved for up to 40 years.

“Texas is a very good place for cold cases,” Bess said.

Ben Thompson contributed to this report.