“Coming out of slavery with virtually nothing and the injustice that was stored upon them, I can only imagine the challenges they were faced with to create a better life for their next generations, but they [persevered],” Green wrote in an email. “Education was always a priority for the families. When they settled in their locations, a cemetery, a church and school were their first concerns to put in operation.”

Thomas Amos, a founding member of the community, purchased 130 acres in Kohrville in 1880, according to “Kohrville Connections,” a book compiled by the association, and from there, the community multiplied.

“It’s kind of like a little hidden gem; we’re surrounded by a lot of progression, and we kind of fit in this pocket, and still a lot of people don’t know about the community that’s around them,” association President Cathyrine Stewart said.

Kohrville originally featured a cemetery, a school, a church—still active to this day as Pilgrim Branch Missionary Baptist Church—and a large hall for the Farmers Improvement Society, where the community would gather for canning and quilting, Green said.

As the community hall has since been demolished, the association is raising money and seeking sponsors for a new community building to place between the cemetery and church building, Green said.

“That would give everyone in the community the opportunity that we can share in this building as we did before and give the community something that can really make them feel proud,” Stewart said.

Cemetery association information states that at least three school buildings served Kohrville until schools were integrated in the late 1960s. Land for the first school, the Kohrville (Colored) School, was purchased for $5 by the trustees of School District No. 1 Colored School No. 2 in January 1893, “Kohrville Connections” states. One of the school buildings is preserved at the Klein Museum complex.

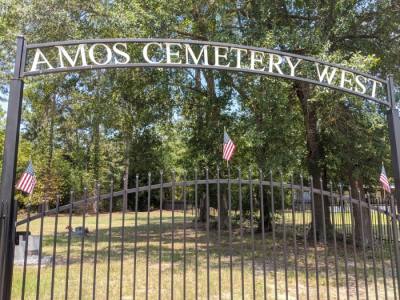

The cemetery, named Amos Cemetery and split east and west by Hufsmith-Kohrville Road in 1906, was honored as a historic Texas cemetery in 2011 with the oldest known headstone dating back to 1915. The association estimates there were at least 144 burials as of March 2011 in Amos Cemetery east and west.

“There are no records that we know of documenting the first burial. African American history in the earlier years was mostly oral and with some documented in the family Bible, which over the years were destroyed due to deceased family members’ destroyed homes,” according to “Kohrville Connections.” “There are many unmarked graves in Amos Cemetery and few records to clearly identify how many there might be. Due to its once-remote location and the segregation laws that were in place for the first 70 or 80 years of its existence, there are few published obituaries and less-than-complete civil death records for those buried here.”

As headstones and markers had deteriorated, the community association was formed in 2007 to preserve the grave sites, Green said. The association raises funds via an annual festival—canceled this year due to the coronavirus pandemic—and donations.

The cemetery association has also renewed its efforts restoring Willis Woods Cemetery, located in the Lakewood subdivision near Louetta and Jones roads. Willis Woods, who later moved into Tomball, was one of the first to purchase property in the Lakewood area.

Prior to settling in Kohrville, the families stopped near Faulkey Gully, but this area has always been prone to the flooding of Cypress Creek, Stewart said.

“The reason they moved from there is that creek has always flooded,” Stewart said. “It pretty much wiped out all the crops and destroyed most of the buildings, and at that time, that’s when they ... prospected Kohrville and found a place where they would have enough land to do what they wanted to do.”

The association celebrated a historic tree planting with Precinct 4 earlier this year at the cemetery and has been working with Precinct 4 to gain better access to the cemetery, Green said.

“Back in the day they kind of land-locked our cemetery in. So we’ve been having Precinct [4] help us get an easement so we can come in and clean and so forth and so on,” Green said.

The association was also poised to launch a scholarship program at this year’s festival to educate youth about the community’s history, said Stewart, whose family has lived in Kohrville for generations.

“My father did peanuts for the government. ... When they started doing peanut butter, he was a major role in that by growing peanuts on this land,” she said. “The ancestors that moved here, our families, they were very smart people; they did a lot of great things. I think through generations you do sometimes lose some of that, so we just like to keep a lot of that in front of our children that are coming up.”

Green's family ties date back to Kohrville's early history as well, she said.

"It gives you a sense of pride. ... They came from such an unfair, unjust [circumstance], but they still made it. The obstacles, the perseverance, they never gave up," she said. "It’s just the perseverance of constantly trying to make things better, not letting the generations forget where they came from, who was involved, who was the one who made it possible for us to be at the level that we are now, and it’s our job to constantly educate."