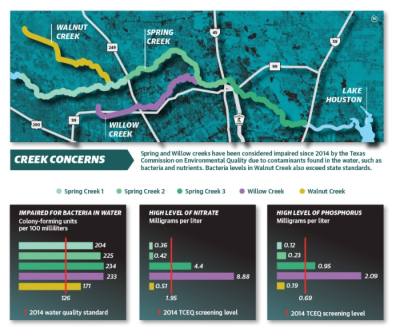

The group’s formation comes as bacteria levels have now surpassed state standards in three local creeks: Spring, Willow and Walnut—all of which flow into Lake Houston, a central regional drinking water source.

Supported by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Houston-Galveston Area Council, a regional planning organization, the partnership’s goal is to create and implement a protection plan by 2021 to guide regional efforts to improve the water quality throughout the Spring Creek watershed.

During the partnership’s first meeting in July, members noted Spring Creek’s importance is related to its eastern flow into Lake Houston, which could be affected by rising levels of fecal waste and other nutrients over the coming years. Additionally, experts said high levels of these contaminants can result in risks to human health and the environment.

Al Rendl, the president of the North Harris County Regional Water Authority—whose jurisdiction includes the Greater Tomball area—said Tomball does not receive drinking water from Lake Houston, but portions of the Greater Tomball area can expect to receive drinking water from Lake Houston as early as 2025 as the region converts to more surface water sources. Although the water is purified, bacteria in runoff from Willow, Walnut and Spring creeks could make filtering drinking water more difficult.

“Any runoff, stormwater runoff and even sewer treatment plant runoff water that goes into creeks and bayous ultimately finds its way into Lake Houston,” Rendl said. “It is then treated and purified to potable drinking water standards that are as good as any water you’re going to find.”

Contributing contaminants

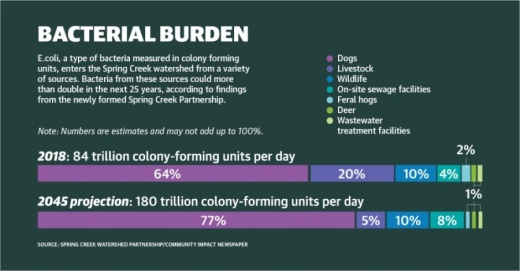

Spring Creek, which borders Harris and Montgomery counties, has been considered impaired by the TCEQ since 2014 because the levels of bacteria in the water exceed state standards, specifically for E. coli—a sign of high levels of fecal waste and other possible pathogens affecting water quality. As a result of health concerns, residents are discouraged from activities such as swimming or boating in these waters.••In Spring Creek from Kickapoo Creek to Hwy. 249, TCEQ data from 2011-18 shows 204 colony-forming units of E. coli per 100 milliliters, exceeding the state standard of 126 units. In Willow Creek, nearly twice the state standard—233 units—was recorded.According to H-GAC planner Rachel Windham, the main culprit of bacterial contamination throughout the Spring Creek watershed is dog waste, which accounted for nearly two-thirds of the daily estimated amount of pollutants entering the water in 2018.

Windham said other identified contributors are livestock, such as cattle and horses; wildlife; and human waste stemming from sewage facilities or sewer overflows—one of the more significant, while less common, human-caused effects.

“These can be very significant events that really contribute to bacteria loading in the system, and they’re extremely harmful, potentially, to human health, as these events represent a large volume of pollutants,” Windham said.

Willow Creek, which merges into Spring Creek, has also been deemed impaired by the TCEQ since 2014 from high levels of bacteria.

According to the Bayou Preservation Association, a nonprofit promoting water quality in the Greater Houston area, nearly half of the drainage from the city of Tomball flows into Willow Creek.

In addition to bacteria, TCEQ data shows nitrate and phosphorus have been found in Willow Creek and the eastern portion of Spring Creek. While essential for the ecosystem, these nutrients in excess can result in high algal blooms that threaten aquatic life and can cause abnormalities in the taste and smell of drinking water as well as human health issues, according to the H-GAC.

Residential effects

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, typically harmless bacteria such as E. coli can indicate the presence of waste containing more harmful organisms that can cause illnesses with symptoms ranging from minor stomach discomfort to death.“There are some [types of] E. coli that would make you sick, but most of the ones that are tested for are quite harmless to us, but [that data is] indicating that something might be amiss,” said Tom Douglas, a member of the Bayou Preservation Association’s Council of Advisors.

Based on 2018 metrics, the total amount of bacteria entering waterways daily is expected to more than double within the next 25 years in Spring Creek, led by a more than 20% increase from dogs alone as development and population growth in the region continues.

Windham said the partnership will use those metrics to solidify its goals for contaminant reduction to develop its potential long-term fixes for the area as planning continues over the coming year.

With the city of Tomball contributing runoff to both Spring and Willow creeks, Community Development Director Craig Meyers said the city is required by the TCEQ to do its part in improving water quality.

Meyers said the city has sought to improve the water quality by strengthening its enforcement of codes for construction site runoff; creating annual events such as the Tomball Consolidated Recycling Day; and increasing public awareness through placards and other signage around city parks, construction sites and public areas.

“There’s a whole laundry list of things that the city has to implement in order to be in compliance with the state regulations in regards to water quality,” Meyers said.

Farther north, Walnut Creek, which also flows into Spring Creek, was recently deemed impaired by the TCEQ from high levels of bacteria in the water. In October, Walnut Creek was added to a 2013 implementation plan to remedy bacteria and water quality for Houston-area waterways.

The plan, developed by the H-GAC’s Bacteria Implementation Group, contains policy recommendations for the creek’s improvement, such as stormwater management or public education on water quality. Because Walnut Creek has been added to the plan, strategies from the plan will be implemented to remedy high levels of bacteria in the creek.

Plans of action

During the Spring Creek Partnership’s Oct. 8 virtual session, Windham shared the results of recent water quality assessments that resulted in identifying goals for reducing waste-related bacteria in two areas.Those include a headwaters area west of Hwy. 249 and north of FM 2920 as well as downstream areas from Hwy. 249 and Mill Creek through north Harris County and south Montgomery County to the West Fork of the San Jacinto River.

Based on analysis of the past decade of state records at monitoring stations in the subwatersheds, a 49% reduction in the western headwaters and a 63% reduction in the eastern downstream portion are needed as a growing population brings new potential waste and bacteria contamination.

“It’s important to look to the future when we’re considering bacteria loads in this system because we want to be sure that we’re not just answering the question of, ‘How do we improve water quality today?’ but also, ‘How do we account for how this land area’s going to change over time?’” Windham said.