Buendia Concrete, owned by Buendia Enterprises, a sand and gravel supplier in Magnolia, has filed an application with the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality to construct a plant at 1301 Superior Road. A virtual public meeting held by the TCEQ is slated for June 7.

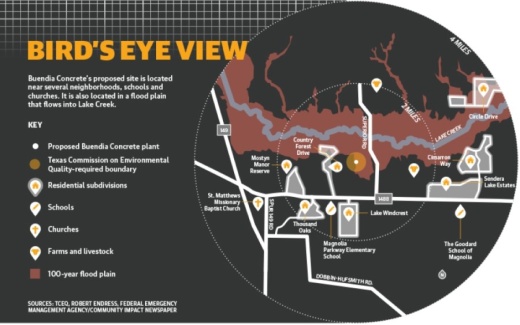

Concrete batch plants release dust and particulate matter made of fine grains of sand and silica into the air that can that can cause respiratory issues and scar lung tissue, said Corey Williams, the research and policy director of Air Alliance Houston, a nonprofit advocating to reduce public health effects from air pollution. Because the proposed facility is located in a flood plain, residents said the facility could contaminate Lake Creek, which flows into the West Fork of the San Jacinto River.

“If this proposal is approved, our lives will be shattered. Our peace will be shattered,” Resident Graham Marshall said.

Meanwhile, Buendia Concrete President Alejandro Buendia said he has read through all of the written concerns and believes many residents are confusing his proposed facility with a cement plant, which releases other emissions.

“At a concrete plant, you don’t have the emissions with some of the gases that the neighbors are confused [about],” he said.

The company’s proposed operations fall within the TCEQ’s guidelines for a standard permit. The agency’s permitting process requires concrete batch plants to meet various specifications that, if followed, will pose no threat to the environment or public health, according to the TCEQ.

Still, residents and elected officials, including Montgomery County Precinct 2 Commissioner Charlie Riley, said although Buendia Concrete may meet the requirements for a permit, the larger problem is the regulatory framework. Riley said he believes permits are granted too easily. In 2020, the TCEQ approved 220 of the 251 concrete batch standard permit applications that were submitted and denied just one of them. The remaining were either pending, incomplete, withdrawn or void, according to information from the TCEQ obtained via an open records request.

“If I wanted to open up a concrete plant, all I’ve got to do is take a [notice and] stick it out in the ditch in front of the property, ... and I’m pretty much assured that I’m going to get me a concrete batch plant permit,” Riley said. “I’ve told TCEQ this ... I’ve told our senators this. That process has got to be changed. That’s no way to do business in 2021.”

Air, water and traffic

Residents’ primary concern with the proposed Buendia Concrete plant is the potential air and water quality effects, as well as increased traffic.

“As senior citizens with respiratory issues ... we have serious concerns regarding the potential impacts,” wrote Clinton Rayes, who lives within 2 miles of the proposed site in the Mostyn Manor subdivision.

TCEQ regulations require a proposed site to meet a setback distance of 440 yards from a residence, school or place of worship. But the community fears materials from the plant will disperse in the water and affect the entire watershed. The field the plant would be located in has flooded three times this year, Marshall said.

“How can you possibly imagine the toxins will neatly remain within that 440 yards when you have water carrying ... those toxins throughout our river system?” he said.

The site is also located within 3 miles of several neighborhoods, churches and schools. Residents also claimed increased truck traffic could disrupt the peace and tear up the road.

Buendia said he would run between 10 and 15 trucks daily. He also said that compared to nearby competitors, he believes his site is the closest to fast-developing areas in Montgomery County like FM 1488 and 2978, which translates to less traffic and emissions.

According to the TCEQ, the ingredients that make up concrete such as water, cement, and aggregates such as sand and gravel are considered nonhazardous.

If concrete batch plants meet permit requirements, they are not determined to be of concern to public health, according to the TCEQ. A public notice issued by the TCEQ on March 19 stated because Buendia Concrete met all permit guidelines, a TCEQ director gave a preliminary decision to issue registration.

Josh Leftwich, president and CEO of Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association, a state trade association, said concrete plants are necessary to Texas’ growing concrete industry. Leftwich said he lives within a mile of two concrete batch plants.

“The permits that are in place are very protective of the environment if they are operated correctly,” he said. “I think most companies want to be good neighbors.”

Regulation concerns

Environmental and public health advocacy groups said they believe individual concrete batch plants are just symptoms of a statewide problem. Williams said the permit process essentially consists of filling out a standardized form.

“They just fill in the boxes and pretty much get their permit granted,” he said.

TCEQ states its permitting process only regulates air emissions and that water quality is not within the scope of the standard permit. The agency also does not have the authority to consider a plant’s location, aesthetics or effects on property values when determining whether to approve an air permit.

Advocacy groups are also concerned there is little oversight once a concrete batch plant is built. In theory, if a plant follows its permit guidelines, there will likely not be detrimental environmental or public health effects, Williams said. The problem is companies do not always operate according to regulations, he said.

A 2016 audit conducted by the city of Houston Bureau of Pollution Control uncovered 44 violations among 39 investigations of concrete batch plants within city limits.

Robert Endress, the president of the Sendera Lake Estates Homeowners Association, a neighborhood within 2 miles of the proposed plant, said he fears the burden of monitoring will fall on residents.

“Once a plant is installed, the onus is on the public to point out issues and potential violations,” he said.

Endress also said there is no holistic review that takes into account noise, traffic, and air and water quality effects.

“No one is stepping back and saying, ‘Is this really a safe and appropriate place for a plant?’” he said.

However, Buendia said facilities are required to submit discharge monitoring reports to the TCEQ, and inspectors regularly come to visit plants. He added that he has seen facilities operating outside of compliance, and he will ensure his plant follows strict protocol.

“I’ve seen ... facilities that are not up to par, .... and I’ve seen facilities that go above and beyond,” he said. “All of these requirements are going to be complied with.”

Legal action

Endress said the community has organized a GoFundMe to pay for legal fees for attorneys. However, few legal options exist.

Williams said the best course for residents in most concrete batch plant cases is via a contested hearing, a court hearing where a judge issues a final order. This occurs if an applicant’s proposed site falls within 440 yards of residential homes.

Buendia Concrete’s original application did trigger a contested hearing, but the company withdrew its original application, according to a March 31 letter from the TCEQ. At first, residents were relieved, Endress said. But Buendia Concrete then refiled for a permit for a site a short distance away with several modifications that made a contested hearing no longer applicable.

Residents believe this was a way for Buendia Concrete to avoid a contested hearing, and Williams said he has seen this tactic used in rural areas. Buendia denied these allegations and said when he refiled his permit, the new location in a flood plain required more stringent requirements than a standard permit. He said he is willing to meet with residents to discuss their concerns. ••“All you’ll have to do is just reach out,” he said.

Meanwhile, Endress said he fears despite community efforts, the proposed Buendia Concrete plant will still move forward. In 2017, a proposed plant on Old Hockley Road caused a similar stir, according to previous reporting by Community Impact Newspaper. However, the permit was granted, and the plant is in operation.

“Are we just spinning our wheels?” Endress said.

Additional Reporting by Anna Lotz