As of early 2022, incidents of family violence—which include emotional, financial, physical and sexual abuse—have remained high since the pandemic began in March 2020, according to local law enforcement officials.

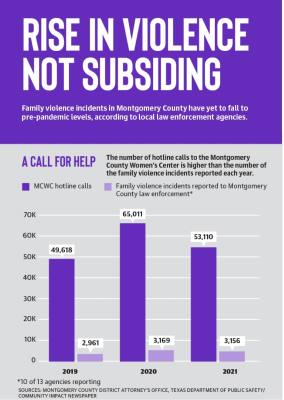

Because local and county incidents have not fallen to pre-pandemic numbers, area women’s centers continue to juggle the demand in services.

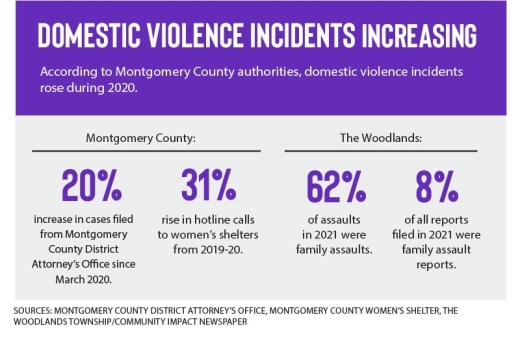

Echo Hutson, chief prosecutor of the Domestic Violence Division at the Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office, said in Montgomery County the number of filed domestic violence-related cases increased an average of 20% each month starting in March 2020 from the previous year. The rise in cases remained at a steady rate through 2021, with some months reaching as high as a 50% increase.

“Last year in 2021, after Montgomery County wasn’t locked down anymore and we were trying to get back to normal ... I went and pulled all the stats again,” Hutson said. “And we had the same 20% increase all the way through 2021.”

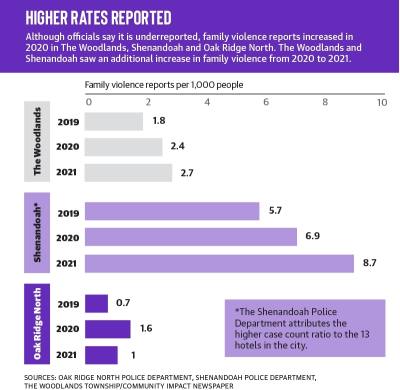

Family violence reports filed in The Woodlands Township increased 33% from 2019 to 2020, and an additional 15% from 2020 to 2021. In 2021, family violence reports made up nearly 8% of all reports filed by law enforcement in The Woodlands, and more than half of all reported assaults were family assaults.

According to Tim Holifield, captain of the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office South Patrol Division, the township also saw an additional increase in family violence reports from 2020 to 2021.

“We actually have a slight increase on family violence over 2020, which was a little bit of an increase [over 2019],” Holifield said during a township board of directors meeting Jan. 26. “Sometimes things get boiled over into arguments and even some that result in domestic violence and battery.”

Shenandoah and Oak Ridge North, cities which each have a population of roughly 3,000, both saw an increase in reports filed from 2019 to 2021, according to data from the cities’ police departments. Despite the rise in reports, officials say they anticipate family violence is still heavily underreported in the area.

Joel Gorden, sergeant detective with the Shenandoah Police Department, said a variety of factors discourage victims from reporting family violence such as financial implications, manipulation, fear of homelessness and fear of violence.

“[Domestic violence] is different because you’re in a relationship with somebody,” Gorden said. “It’s not like some stranger is assaulting you and you can call the police and your problem gets solved.”

Underreported incidents

According to a criminal victimization survey released by the U.S. Department of Justice in October, 52% of victims of domestic violence reported the crime to police in 2019. In 2020, 41% of victims reported the crime.

Ling Ren is a professor and graduate program director at the Sam Houston State University Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, specializing in a variety of topics, including domestic violence prosecution. She said there are several reasons for underreporting.

“It is well documented in the literature that many victims of [family violence] do not make criminal complaints or call the police due to a variety of concerns,” Ren said in an email to Community Impact Newspaper. “I believe during COVID[-19], the underreporting problem was exacerbated by social isolation, stay-home orders, illnesses and increased substance abuse.”

Ren said national estimates of underreporting may be determined by comparing national incident reports with self-reported victim surveys. However, Ren said there are no regional or jurisdictional variations addressed in the national-level estimates.

“There are also disagreements [and] debates among academia about the methods that were used to estimate the dark figure in family violence, so it is a big swamp,” Ren said, referring to underreported crime figures.

While Texas officers are required to file a report for all family violence incidents, the largest issue when determining the accurate number of assaults is that victims often do not make themselves known or report every incident to law enforcement, according to Hutson.

“Seventy-eight percent of the calls [to law enforcement] come from people who are not the victim. They come from family, neighbors, friends, coworkers,” Hutson said. “When victims do call themselves, the vast majority of it is in the moment of crisis when they think they’re either not going to make it out alive or they’re going to be seriously hurt or injured.”

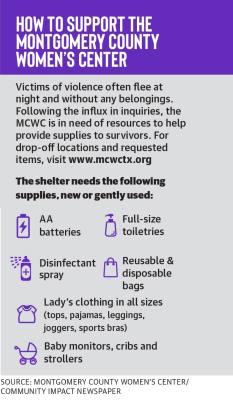

Hutson said victims are more likely to reach out to local support systems, such as the Montgomery County Women’s Center.

Ten of the 13 law enforcement agencies in Montgomery County provided family violence reports to the Texas Department of Public Safety Uniform Crime Reporting System. According to the data, there were 2,961 reported incidents of family violence in Montgomery County in 2019. However, according to Hutson, there were 49,618 hotline calls to MCWC.

In 2020, the incidents increased roughly 7%, while hotline calls increased 31%. In 2021, incidents and hotline calls were still 6.6% and 7% over 2019, respectively.

“I think [we need] education, awareness, understanding and also for the community [to understand] that we’re talking about one in three women,” Hutson said. “It’s so prevalent. It’s everywhere; but it’s behind closed doors.”

Center services strained

On Sept. 10, 2020, 93% of identified domestic violence programs in Texas participated in a one-day national count of domestic violence services conducted by the National Network to End Domestic Violence. The national count found 948 requests for services on this day were unmet due to a lack of resources.

Both the MCWC and Houston Area Women’s Center—which often work together to place victims in the Houston region—continued to see increased inquiries and strained resources through 2021.

Chau Nguyen, chief public strategies officer for the Houston Area Women’s Center, said the center saw roughly a 16% increase in hotline calls from 2019 to 2020 and an additional 17% rise from 2020 to 2021. HAWC offers services to victims throughout the Greater Houston area and in Harris County.

Nguyen said HAWC has a 120-shelter bed operation, and despite being the largest shelter provider in the Houston region, the center occasionally turns people away.

“On any given night, our shelter beds are full. There is a large demand for emergency housing,” Nguyen said. “Sometimes we have to turn away people.”••Both the MCWC and HAWC sometimes place victims in hotel rooms when beds are full.

“It’s a program we used pre-pandemic, making two or three placements a month,” Nguyen said. “During the pandemic, we used it 20, 30, 40 times a month because of additional funding.”

Legislation aimed to help victims

According to the Texas Council on Family Violence, five bills passed in the 87th Texas legislative session in 2021 that benefit victims of domestic and family violence. Hutson said she believes House Bill 766 is significant as it improves the immediate safety of a victim.

Judges may issue conditions of bonds to protect victims from a person arrested for domestic violence, and prior to HB 766, law enforcement officers were unable to verify conditions of bonds in the Texas Crime Information Center, meaning they generally could not enforce the conditions of bond. As a result, victims, law enforcement, and the community remain at risk, and offenders are often not held accountable if they violate conditions of bonds.

The bill, which went into effect Jan. 1, requires the sheriff to enter the conditions of bonds into the Texas Crime Information Center, so they are accessible and verifiable by law enforcement.

Additional pieces of legislation were passed to help survivors escape abusive situations by removing financial barriers victims may face, such as fees associated with breaking cell phone plans and obtaining birth certificates and drivers’ licenses.

“[Ending domestic violence] takes an entire community because we know domestic violence doesn’t just affect a person—it affects the entire community,” Nguyen said. “It has this cascading effect on the first responders and the children that witness violence, the hospital system, our workplace.”