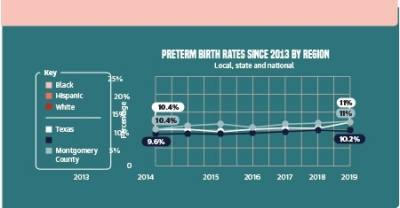

The county earned a D with a preterm birth rate of 10.7% in a 2021 survey that reported birthrates of babies born prior to 37 weeks for counties nationwide. Texas also received a D with 10.8% of all births considered preterm. The annual report also includes data on infant mortality rates, racial disparities, vulnerability and access to prenatal care.

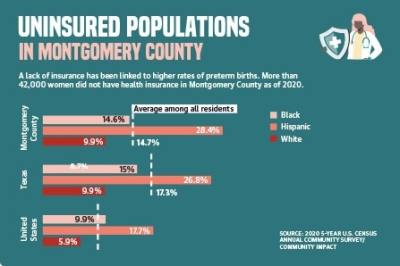

A lack of access to prenatal care in certain geographical areas of the county widens the gap in preterm births among races. Uninsured women often do not receive prenatal care at an appropriate time, leading to a higher chance of complications, such as preterm birth and hypertension, according to the March of Dimes, a nonprofit that promotes research and education for maternal and infant health.

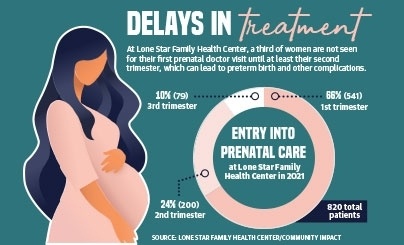

Karen Harwell, CEO at the Lone Star Family Health Center, a Montgomery County nonprofit clinic that serves primarily underserved communities, said a large number of its prenatal patients do not get seen until the third trimester of pregnancy.

“Those are horrendous rates,” she said. “We try to do a ton of community education and work with partners that may come across women that they can refer to us earlier rather than later.”

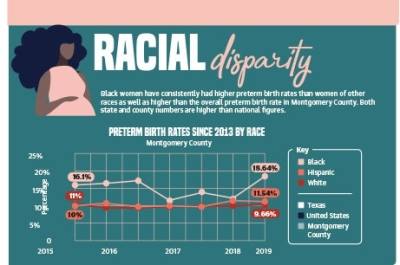

Racial disparities

One of the largest areas of concern in Montgomery County was the discrepancy in preterm birth rates between Black and white women. Jennifer Torres, senior executive director for the March of Dimes Greater Houston, said in the 2021 report, which highlights data from 2019, white and Hispanic women had preterm birth rates of 10% and 11%, respectively, while Black women had a preterm birth rate of 16.1%.

“That’s a big discrepancy, especially when you look at other counties like Harris County, Fort Bend—there isn’t as big of a gap there,” Torres said.

Heather Butscher, maternal and child health director for the March of Dimes Greater Houston, said the organization has developed training for health care providers on implicit bias and other factors that could affect how service is provided. Implicit biases, she said, are imprints that all people are born with.

“Our brain is wired to create shortcuts—when we see people, we create inferences about them that we really can’t control, but we need to be aware of them,” Butscher said.

She said the training focuses on teaching providers how to leave their biases at the door.

Torres said she recently spoke with a Black woman from Montgomery County who did not receive the care she needed after giving birth because she said she was not taken seriously.

“She’s a physician, and she kept telling her provider 48 hours after she gave birth—she wasn’t feeling right—but just didn’t get the attention that was needed,” Torres said. “We hear women, they go home, and they die a few days later after childbirth because of a condition or a situation that wasn’t taken care of.”

Harwell said a high percentage of Lone Star Family Health patients are Hispanic or Black and often are being seen for the first time too late into the pregnancy. Out of 820 total deliveries at the clinic last year, 34% did not receive care until at least the second trimester.

“We had 200 of those that started prenatal care in their third trimester, which is horrendous,” Harwell said. “Over one-third did not receive care until their fourth month, which is also horrendous.”

Access to prenatal care

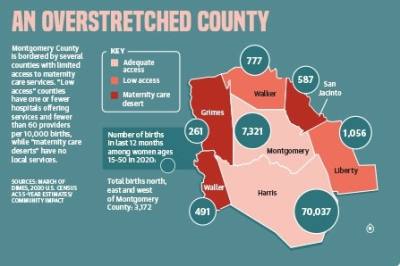

Women on the edges of Montgomery County may have a more difficult time accessing adequate prenatal care, Torres said.

“The counties surrounding—they are considered maternity care deserts, which means there’s little or no access to maternal care,” she said.

On its north, east and west sides, Montgomery County is surrounded by counties with low access to prenatal care or by maternity care deserts—defined as a county where no hospitals provide obstetric care and there are no birth centers, no obstetricians/gynecologists and no certified nurse midwives.

Butscher said much of March of Dimes’ work involves ensuring hospitals and clinics are closely aligned so mothers are able to remain in the area through birth and continue follow-up care close to home.

“In Montgomery County, we have the satellite hospitals; we have Lone Star [Family Health Center] covering our Medicaid population,” she said. “We know that there are some areas, though, where it’s just difficult for whatever reason to get to a physician’s office or a hospital.”

Hospitals in The Woodlands area include Memorial Hermann, Houston Methodist, St. Luke's Health and Texas Children’s Hospital.

But there are some areas even in Montgomery County where expectant mothers may find it difficult to get prenatal care, including the Tamina community east of I-45, East Montgomery County, New Caney and the outskirts of Conroe.

“We know there’s places where there’s not even good roads, let alone a bus route to get you to your obstetric provider,” Butscher said. “Women and families, ... they have to choose priorities. Gas is also expensive, even if you have a car. If you have to go that long distance, there’s so many barriers.”

Harwell said around 37,000 people in Montgomery County go to a community health center for services.

In areas such as Tamina—a Montgomery County community east of Shenandoah that has a largely Black population—community members may be less likely to seek care due to cultural norms and a lack of trust in health care systems, Harwell said. To reach those communities, Lone Star tries to mirror the demographics of its patients in both its staff and board of directors.

“It’s amazing, just subconsciously, the level of kind of trust and just connection that you feel with someone when they kind of share a similar background,” she said.

Finding solutions

While Lone Star Family Health Center sees a few patients with private insurance, Harwell said the vast majority are uninsured or on Medicare or Medicaid. For uninsured women, one barrier to receiving care is knowing whether they qualify for coverage.

“Off the bat we try to make sure people can qualify for any type of third-party coverage,” she said. “Most of the time for pregnant women—and they may or may not know it—there is coverage for them.”

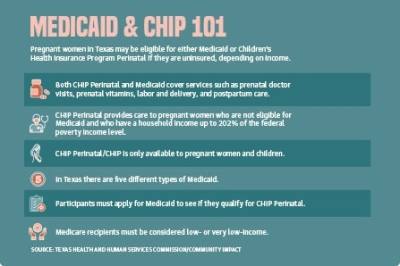

In Texas, pregnant women are eligible to receive coverage through Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program Perinatal.

According to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, 426,432 pregnant women were reported to be on Medicaid or CHIP Perinatal as of June, a 31% increase since June 2021.

Although many women are eligible to receive coverage, it can be administratively burdensome if they discover they are pregnant prior to beginning the process, Harwell said.

“You need to determine whether you could be eligible, then wait and see if that eligibility actually comes through. If you sit around and wait for all of that to happen, you’re in your second trimester,” Harwell said.

Torres said the majority of women on Medicaid do not get to a prenatal visit until at least the fifth month of pregnancy.

In addition to implicit bias training, the March of Dimes has launched two other initiatives to help reduce preterm births and improve care.

The hypertension awareness initiative involves the distribution of blood pressure cuffs and education to high-risk, low-income pregnant women. Another initiative, Beyond Labels, establishes a statewide health care network to help mothers dealing from mental illness during and after pregnancy.

Local hospitals, including Memorial Hermann, are also taking steps to address prenatal health care issues. In April 2021, it established a Maternal Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Council to address racial disparities in treatment.

Butscher said prenatal support efforts extend across multiple sources of health care.

“It’s not just the hospital; it’s not just the clinic; it’s not just the provider—it’s what we can do as communities to support moms and families,” Butscher said.