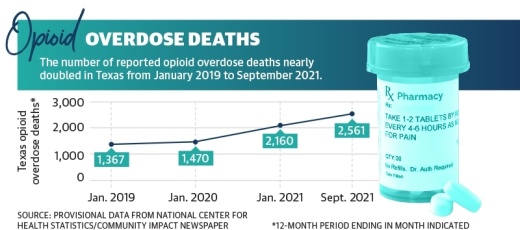

Information from the Texas attorney general’s office indicates in 2020, drug overdose deaths had increased by around 32% from the previous year, driven primarily by opioids. However, provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics has shown reported opioid overdose deaths nearly doubled in Texas from January 2019 to nearly doubled in Montgomery County from January 2019 to January 2021, and there was an additional 19% increase in deaths from January 2021 to September 2021, the most recent data available.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

With increased isolation and financial stresses, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated struggles against the opioid epidemic in Texas. Recovery treatment transitioned into less effective online services, and access to quality treatment, such as medication, became more complicated, according to local experts.

Opioid usage varies

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As a result, these drugs, which had formerly only been prescribed to treat acute pain, became the prescription of choice to treat chronic, long-term pain.

“One thing that’s been good for Montgomery County specifically, if you look in 2020 [and] 2021, there were three or four significant arrests of doctors in Montgomery County who were writing prescriptions to people—essentially illegally—allowing them to have access to these prescription pills when they didn’t really have a diagnosis for it,” said James Campbell, chief of emergency medical services for the Montgomery County Hospital District. “[Law enforcement] worked to arrest those doctors and get them out of practice, which has been a huge impact.”

In 2020, a little more than one prescription was issued on average for every three residents in Montgomery County. However, the dispensing rate has been cut in half since 2014, and from 2019-20, it declined 19%. Despite declining opioid dispensing rates countywide and across the state, total reported drug overdoses in Texas increased 33% from 2020-21, according to the NCHS.

Campbell said opioid overdose deaths remain constant; however, according to the NIDA, opioid usage can lead to illegal drugs that are not prescribed, such as heroin. According to the NIDA, nearly 80% of heroin users reported using prescription opioids prior to heroin.

“I think because the way Montgomery County is situated with the major highways on either side of the county, a lot of things pass through, and prescription pills usually are consistent,” Campbell said. “Heroin and [other] things come and go as drug trafficking comes and goes.”

Pandemic effects on treatment

Varisco described several underlying causes of substance use disorders that the pandemic exacerbated, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation. Varisco said he believes the drastic changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid recovery work performed for patients before the pandemic.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification treatment discharges became less common from 2016-19, when detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16%. This did not change the patient completion rate of detoxification treatment, which remained stable with fewer than half of patients completing treatment.

“When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

With in-person treatment at risk due to the coronavirus, health care centers went remote in 2020. Many centers were limited to offering substance use disorder care through telehealth services as opposed to in-person, personal programs, complicating opioid recovery for patients.

Katy Franklin, a substance use counselor at Conroe-based Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare, said the transition was difficult for patients. A federally qualified health care organization, Tri-County’s substance use program serves 13 counties, including Harris and Montgomery counties.

“It’s not the same level of care; you’re missing some things over Zoom that you wouldn’t [miss] in-person,” Franklin said of telehealth treatments. “Treatment was less effective for this particular population.”Despite being less effective, telehealth did allow some smaller clinics and private practices to expand their coverage areas. Lori Fiester, the clinical director at the Houston-based nonprofit Council on Recovery, said telehealth allowed patients without transportation access or those who are immunocompromised to receive care.

“We’ve had people across the state in our groups, including in the Austin area, which was really helpful for our groups to stay vital,” Fiester said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Varisco said there was some confusion about what treatments were acceptable. A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission executive commissioner, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation.

According to SAMHSA, buprenorphine and methadone are Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs used in combination with counseling to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Some barriers for treatment go beyond drug-related issues. Varisco, Fiester and Franklin agreed the lack of accessible public transportation in Texas increased difficulty for lower-income patients.

“If you’re prescribed for buprenorphine or methadone or whatever, you have to take a bus across the city [of Houston] to get the prescription,” Varisco said. “Proximity to care is just not there.”

Government solutions

State and county entities are working to address the opioid epidemic and the effects the pandemic had on recovery through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

Campbell said law enforcement initiatives, including the use of naloxone—an overdose emergency treatment—were implemented in 2019 to help curb an opioid overdose increase in Montgomery County.

“We train and educate law enforcement on how to use Narcan [device that delivers naloxone],” Campbell said. “When they arrive to a patient who’s not breathing from an overdose, they’re able to give the Narcan before the ambulance even arrives.”

According to Campbell, the MCHD administered naloxone 309 times in 2019, 304 times in 2020 and 375 times in 2021.

Statewide, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 that the state had secured a $1.17 billion settlement with three major pharmaceutical companies: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, and Cardinal. According to the attorney general, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements.

“Texans have been devastated by the opioid crisis, and it is important that this settlement is proportioned fairly among the communities that need it most,” Paxton said.

Paxton’s office has also reached out to local governments, encouraging them to sign on to existing settlements to receive funds. According to the attorney general’s website, 482 Texas municipalities signed on to two settlements with Janssen—owned by Johnson & Johnson—and with AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson.

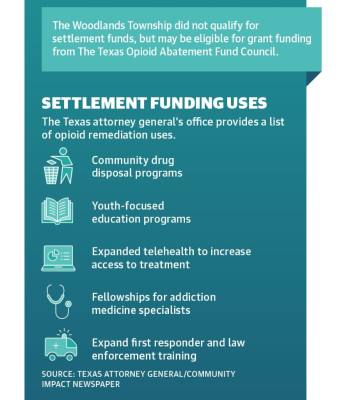

As of Feb. 24, Oak Ridge North was allocated approximately $33,512 from the settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors, and Shenandoah was allocated $47,122, according to the attorney general’s website. The Woodlands Township joined the settlement as well, and while the township did not qualify for direct settlement payments, it could receive grant funding from the Texas Opioid Abatement Fund Council, according to township documents. A list of funding uses provided by the attorney general’s office includes community drug disposal programs, training for first responders, and youth-focused programs that discourage or prevent misuse. Campbell said he believes early education is effective to prevent addiction.

State Senate Bill 435, which took effect in September 2019, directs local school health advisory councils to recommend appropriate opioid addiction and misuse curriculum for their districts. According to Conroe ISD officials, new health instructional materials are under review dealing with opioid use and addiction.

“We’re fortunate in Montgomery County,” Campbell said. “We have good resources, good law enforcement, good first responders, fire partners, public health. Montgomery County is doing very well.”