According to the Texas Workforce Commission, the number of child care workers in the Gulf Coast region in 2018 was 19,554. By 2020, the most recent yearof data collected, the number had fallen to 12,310.

Deborah Kaschik, owner of Young Learners Academy locations in The Woodlands and Oak Ridge North, said the facilities have experienced a staffing shortage since the pandemic.

“A majority of our employees that left and didn’t come back found other avenues for employment during the pandemic,” Kaschik said. “Some went back to school and changed careers; some became nannies; ... some did retire.”

Low salaries, high student ratios

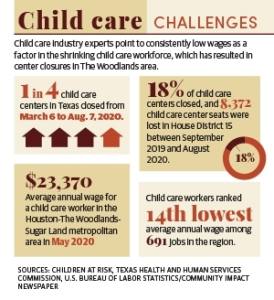

While experts and child care center owners point to early retirement and safety concerns as reasons child care workers did not return, studies show the main reason the industry is losing workforce is because of low wages.

A survey released in September by the National Association for the Education of Young Children reported 86% of child care centers in Texas are experiencing a staffing shortage; 79% of those surveyed identified wages as the main recruitment challenge.

Kim Kofron, the director of early childhood education with Texas-based nonprofit Children at Risk, was previously the executive director for the Texas Association for the Education of Young Children.

“The early childhood workforce is a low-income industry, and the thing about COVID[-19] is [child care] is a high-risk [job] dealing with children, and you’re indoors with lots of little bodies that carry lots of germs,” Kofron said. “If it’s a low-income job, then we’re losing our child workforce too, and that also creates a scarcity.”

In May 2020, The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the average annual wage for a child care worker in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metropolitan area was $23,370—the 14th lowest-paying occupation out of the 691 occupations in the region.

Child care center owners said keeping a low teacher-to-child ratio must be maintained for centers to legally operate. Kaschik said keeping a sustainable ratio requires higher wages, but higher wages raise the costs of parent fees, potentially driving business away. Consequently, area owners are competing with larger companies that may offer higher wages.

“We have raised our hourly rates in order to try to keep who we have and attract more people, but sometimes it’s just hard to compete with big-box stores and retailers that can pay $20 an hour,” Kaschik said.

Kaschik said some days her facilities become so short staffed she pulls qualified front office or administrative staff to step in the classrooms.

Arlena McLaughlin, who operates seven Primrose schools in The Woodlands and Spring, said other staff step in when there are not enough teachers to meet Primrose’s required ratios.

“We didn’t have to close on days we were short [on] teaching staff as our leadership teams assumed the teaching role in classrooms,” McLaughlin said.McLaughlin said Primrose saw a decline in available employees during the pandemic and offered incentives to staff to stay with the company. She adjusted wages, offered bonuses and provided the required pre-service training to recruit new team members.“We were expecting a larger return to work this fall, but it didn’t happen,” McLaughlin said.

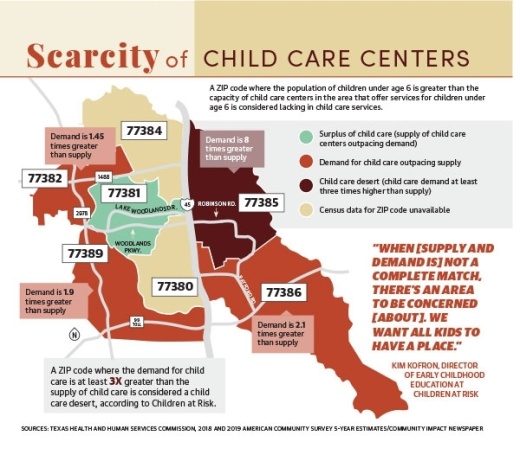

Scarcity in The Woodlands area

The lack of an available workforce forced area centers to close their doors, unable to keep up legally required teacher-to-child ratios. These closures have contributed to the existing child care scarcity in south Montgomery County.Children at Risk studies and monitors child care deserts—communities where the demand for child care is at least three times greater than the supply. The nonprofit released a report in March that found between September 2019 and August 2020, 18% of child care centers closed and 8,372 child care seats were lost due to the pandemic in Texas House District 15, which includes The Woodlands, Shenandoah and Oak Ridge North.Kofron said a variety of factors contribute to the child care scarcity, including the availability of the workforce, traffic patterns, where employers are located, income levels and poverty levels.

However, she said the pandemic increased the number of child care deserts across Texas because of the increase in unemployment and parents working from home, changing the demand for child care and resulting in closures.

“It’s all about parent choice, and I think parents are making different choices now than what they were making two years ago,” Kofron said.

According to census data from the 2018 and 2019 American Community Survey five-year estimates and data from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, in ZIP codes 77382, 77389 and 77386, the population of children under age 6 is 1.45 to 2.1 times greater than the capacity of child care centers that offer services for children under age 6.

“When [supply and demand is] not a complete match, there’s an area to be concerned [about]. We want all kids to have a place,” Kofron said. “Three times is just where we classify that as a desert.”Although there is a surplus capacity in one area ZIP code—77381—one area of the region classifies as a child care desert: 77385, which includes Oak Ridge North and eastern parts of The Woodlands.Demand in Oak Ridge North

The population of children under age 6 is over eight times greater than the capacity of child care centers in 77385. According to Children at Risk, Oak Ridge North was considered a child care desert prior to the start of the pandemic.

The population in 77385 has similar average household incomes, education status and poverty rates to 77381, according to census data. Kofron said a potential factor in the disparity between child care options between the two ZIP codes is traffic.

“I think availability of workforce is a factor. I think the other thing is it goes down to traffic patterns,” Kofron said. “If it’s a community where there’s car traffic [or] public transportation traffic, those are things that all play into that.”

The city’s main thoroughfare is Robinson Road, which city officials said carries more than 16,000 trips a day—a number that is expected to increase—on a two-lane road constructed for local residential traffic.

Kaschik said mobility plays a role in where centers open. As a result of the scarcity of child care options in the Oak Ridge North community, Kaschik has waitlisted classes despite being one of the largest child care providers in the area with a capacity over 180 children.

“Our Oak Ridge location [has] several of the classes full and waitlisted, whereas our Woodlands location, only a couple of the classes are waitlisted,” Kaschik said. “It’s interesting because [they are] just across the freeway. ... I think accessibility is huge when you’re planning where to build that building or open that location.”

Child care sector recovery

Hiranya Nath, an economics professor at Sam Houston State University, said the child care industry has not recovered from the downturn despite the return of other industries.“As the [COVID-19] situation has improved and the economic activities are getting back to some level of normalcy, the demand for child care has gone up,” Nath said. “One of the biggest challenges facing the industry is that many workers in the child care sector have quit their jobs, citing low compensation.”

Nath said President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill may provide a boost to the industry if it passes in the Senate. According to a news release from The White House, the bill would provide $400 billion in nationwide funding to child care and preschool services to expand access to free and high-quality preschool.

“If the worker crisis persists in the child care sector, it may have a domino effect on employment growth in other sectors as some parents will not be able to work as they will have to take care of their children,” Nath said.

A study released in September by the National Association for the Education of Young Children reported 29% of Texas respondents working in child care centers and 11% of those working in family child care homes reduced debt they took on during the pandemic using relief funds. Another 56% expect they will be able to reduce debt with future relief funds.

Kofron said the child care industry may see recovery with state COVID-19 relief funding from the American Rescue Plan Act. She said funds are going through the TWC, which houses and manages the child care subsidy program. The program encourages center owners to open in low-income communities. In addition, she said cities and counties may use it to help small businesses, such as child care centers.

“I think what the pandemic has shown us is, one, how vital child care is for our Texas economy,” Kofron said. “We can’t get families back to work if there’s no place to watch the children.”