This gradual, vertical decline is known as subsidence, or the sinking of the land due to compaction beneath the earth’s surface. The UH study stated the sinking in the Greater Houston area is chiefly caused by pumping water from underground reserves, which compacts sublayers of clay and silt in aquifers beneath the Earth’s surface.

The Woodlands switched to a blend of groundwater and surface water in 2016, using water from San Jacinto River Authority’s surface water treatment plant on Lake Conroe, due to concerns about extracting groundwater, according to The Woodlands Water Agency, which oversees 10 municipal utility districts.

However, officials with the entity that regulates groundwater usage in Montgomery County—the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District—disagree groundwater extraction is responsible for subsidence in the area. Officials said the district launched a study in 2019 to better determine the underlying causes.

“We believe that some of the data has been presented in a way that is misleading,” said Jim Spigener, president of the LSGCD board of directors, regarding remote sensing data used in subsidence studies.

He said satellite data does not provide adequate information about which aquifers are affected, nor does it provide certainty regarding the cause of subsidence.

Groundwater is an affordable and clean source of water, said Shuhab Khan, a geology professor at the University of Houston and one of the report’s authors. He said there is a balance to using groundwater.

“Groundwater is the cleanest water all over the world,” Khan said. “It is a means for drinking, for agriculture, for industry, and when we start pumping more water than the amount of water that is replenishing [aquifers], that balance is gone.”

Over time, subsidence can cause damage to property, pipes and roads, Khan said. It also makes an area more susceptible to flooding.

Although the conditions that cause subsidence can be lessened by cities using alternative sources, such as surface and potable water, the effects of subsidence are permanent, said Robert Mace, water policy director at Texas State University.

“If you reduce your pumping, you can then decrease the maximum subsidence that would have occurred,” he said. “But for the most part, land subsidence is a one-way trip. Once it’s compressed, it’s not coming back up.”

Study findings

The UH report found the biggest contributor to subsidence was the use of groundwater.

Wells can be drilled into an aquifer, which consists of layers of underground, water-bearing rock, and water can be pumped out for use by residents. Since property owners own the rights to water produced from wells on their properties, pumping groundwater is also a property-rights issue,

which officials with the LSGCD have said they want to defend.

“The law in Texas says that the people own the water below them,” Spigener said. “And ... you can’t just go take people’s property away from them.”

However, SJRA General Manager Jace Houston said the relationship between subsidence and groundwater withdrawal has been established, and the UH report offers proof of the impact of groundwater withdrawal.

“This is not something you can just ignore,” Houston said. “You cannot stick your head in the sand and keep pumping all the groundwater you want.”

While The Woodlands has increased its use of surface water from 35% of the total to an annual 50/50 average mix with groundwater as of Sept. 1, Houston said that is not the case in most of Montgomery County, where there are no requirements to use surface water.

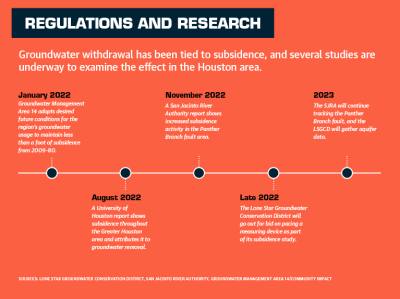

Groundwater Management Area 14, which includes the Greater Houston area, adopted a set of desired future conditions Jan. 5 stating there should not be subsidence of more than 1 additional foot between 2009-80, but the metric is optional for groundwater conservation districts.

LSGCD officials have said they are not restricting groundwater pumping because they believe more data is needed to prove that it causes substantial subsidence, and the district is in the process of obtaining that data with its study evaluating existing subsidence data and obtaining new aquifer data.

“The best science we’ve got right now tells us ... we can expect less than a foot average subsidence in the next 50 years,” Spigener said, referring to models of available groundwater in the Gulf Coast Aquifer System.

Spigener said he believes the rate of subsidence is not at a level that should be considered alarming in Montgomery County.

“Subsidence is important, but the forest is not on fire,” he said.

However, Houston said he sees the problem as more urgent as subsidence leads to more active fault lines and increases flooding effects in the region.

“Water levels will continue to decline; subsidence will continue to occur until someday enough people get upset enough to go and convince the LSGCD to begin regulating groundwater again,” Houston said.

Ongoing research

The UH study pinpointed new hot spots of subsidence in areas including The Woodlands and Spring, citing south Montgomery County as an area of “manifest substantial negative displacement” that will worsen as the population grows.

One indicator of the expected population growth can be seen in a Population and Survey Analysts demographic study presented to Conroe ISD on Dec. 6, which projected growth in the region could lead the district to see as many as 98,000 students by 2032, up from its current enrollment estimate of around 73,000.

To pinpoint which aquifers are seeing the greatest effect from groundwater extraction, Spigener said Phase 3 of the district’s ongoing study into subsidence involves putting an extensometer in place in The Woodlands area to measure the extent of subsidence in the ground by determining changes in soil due to compaction.

However, each device costs $1 million-$1.5 million, and six devices are needed, Spigener said. The process of installing the device takes six to nine months, and prebidding meetings were held in late November for the first device. It would likely take up to two years for the first data to be collected, he said.

“Our [annual] budget is $2 million for the whole district, so it really is a long-term [project]; we’re not going to do this overnight,” Spigener said.

While the district has funds set aside for the first extensometer, Spigener said funding from water stakeholders will be needed for subsequent devices. That would include entities such as the SJRA, the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, the city of Conroe and others, he said.

Despite the doubts expressed by the LSGCD, other water entities in the region said they believe groundwater withdrawal should be regulated.

“Subsidence in Montgomery County is driven by groundwater withdrawl and is well-documented over the past 20-plus years,” said John Geiger, water awareness and education coordinator for The Woodlands Water Agency. “We expect further Woodlands-area improvements in 2023 by using a 50% blend of surface and groundwater.”

Spigener said he will wait for extensometer data results before drawing conclusions about the specific causes of subsidence.

“People take that remote sensing data, radar sensing data, and put it out there and say, ‘Oh my god, we’re pumping too much groundwater.’ And my question is—are you absolutely certain that’s what it is?” Spigener said.

Potential effects

Among the effects of subsidence can be increased flooding and increased fault activity.

H-GSD General Manager Mike Turco said subsidence has also contributed to flooding across the Houston area.

“These [flooding events] are in the same areas where we are seeing subsidence rates at 1 1/2 to 3 centimeters per year,” he said.

In The Woodlands area, one area that has historically been affected by flooding is off Research Forest Drive near The Woodlands High School, said Laura Norton, president of Montgomery County Municipal Utility District No. 47, which serves an area around Research Forest.

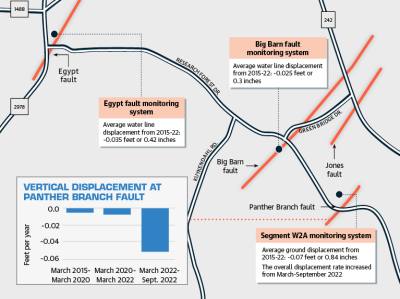

She said the area is also a location where faults run through The Woodlands. The Jones and Panther Branch faults are located near Research Forest, and a November report by the SJRA shows an increase in subsidence in the area where the Panther Branch fault is suspected to cross a water pipeline.

Norton said damage to homes and dips in the road can be seen in the area in the form of cracks in the road, in driveways and foundations.

The UH study states its findings also imply subsidence may be responsible for fault movement in the Greater Houston area based on analysis of land displacement.

“If current ground pumping trends continue, faults in ... The Woodlands will likely become reactivated and/or increase in activity over time,” according to the report.

Norton said she believes that is happening, noting that faulting and subsidence lessens when less groundwater is extracted.

A semiannual SJRA report issued in November showed a marked increased in subsidence at a monitoring system near the suspected Panther Branch fault compared to six months earlier. Vertical displacement increased from 0.008 feet per year to 0.051 feet per year at the site, according to a report.

SJRA Director of Operations Ed Shackelford said a study underway by the SJRA is looking to confirm the fault location, which could mean additional protection is needed for the water line there.

Meanwhile, Houston said the $500 million SJRA plant, which became operational in 2015, is being used at minimum capacity because of the lack of incentives to use surface water. It is not in danger of being shut down, he said, but it is not being used for the purpose for which it was built.

“There’s no regulation so they have no incentive to use any more than necessary,” Houston said. “As it sits unused, some of the equipment can deteriorate. And it can be expensive to start it back up.”

Editor's note: In the print edition of this story the line chart on Page 44 should read "Water level below surface by feet at Research Forest well."