Recent regulatory decisions have highlighted differences in opinion on how groundwater should be managed in Montgomery County with concerns about potential irreversible land sinkage in The Woodlands area pitted against arguments in favor of cost savings and private property rights.

On April 9, Groundwater Management Area 14—which includes the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District, the entity that regulates Montgomery County’s groundwater, and four other districts—voted on its proposed long-term goal for the regional Gulf Coast Aquifer System after months of meetings and discussions.

The goal, known as a desired future condition, or DFC, establishes how much groundwater districts within GMA 14 can pump from the aquifers, which are a series of underground permeable rock layers that provide groundwater for the region. Once formally approved, the DFC will undergo 90 days of public comment before being adopted by Jan. 5, 2022, and it will include plans for what groundwater conditions will look like in 2080, according to the LSGCD.

GMA 14’s proposed goal includes no more than 1 additional foot of subsidence, or land sinkage, from 2009-2080 for the aquifer system. However, officials with the LSGCD—the lone district to oppose the DFC—said they believe protecting property rights should be the priority.

“[That] is really the No. 1 goal,” LSGCD President Harry Hardman said. “That’s how we are going to be managing moving forward.”

However, residents and officials in The Woodlands have expressed concern about the regional effects if subsidence proves to be greater than anticipated. As of April 27, the Houston-Galveston Subsidence District said it has measured 26.7 centimeters of subsidence in The Woodlands area since 2000.

“The real reason that people should be concerned is that if the ground lowers, with the new Atlas 14 [rainfall data] numbers that are being used to compile flood data, the risk is just increased dramatically,” said Bruce Rieser, chair of The Woodland Township’s One Water Task Force and vice chair of the township board of directors. Rieser said in addition to increasing flooding risks, subsidence could do damage to foundations, pipelines, roads and other infrastructure.

“To sustain this community, we just need to be smart,” he said. “I understand the argument about water being a private property right, and that’s great, but there’s also a tenet in all water [regulation] that you are to do no harm downstream.”

‘No harm downstream’

Despite the inclusion of a subsidence goal in the proposed DFC, officials in The Woodlands said they are concerned about the potential negative effects of groundwater withdrawal if it is not constrained over time.The LSGCD was the sole member of GMA 14 opposed to including the subsidence metric in the DFC, advocating instead that the DFC consider metrics applicable to each district based on the best available science.

“The district is advocating for DFC statements that accurately represent the aquifer conditions and geology and for using metrics that are applicable to the districts based on their varying aquifer conditions,” LSGCD General Manager Samantha Reiter said in an email.

Despite objections and alternate motions, the LSGCD joined GMA 14 in unanimously approving the original proposed DFC statement without the language of a formal resolution. A final DFC statement will need to be adopted that includes a formal resolution by early next year.

Groundwater conservation districts are required to consider nine factors such as private property rights, socioeconomic effects and subsidence when proposing a desired future condition. However, the statute does not dictate how much weight each factor should receive.

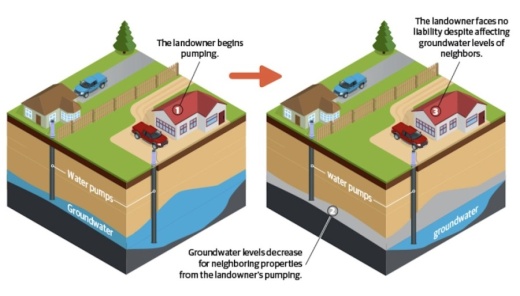

The LSGCD’s objections tie back to Texas’ Rule of Capture, adopted in 1904, which allows landowners to pump as much groundwater as they choose without liability, regardless of if that dries up a neighbor’s well. Groundwater conservation districts were created by the Texas Legislature in 1949 to regulate groundwater, and they issue pumping permits to local entities.

Jim Stinson, general manager of The Woodlands Water Agency, said the county saw reduced subsidence rates after groundwater withdrawal countywide was reduced in 2016 and surface water from the Lake Conroe treatment plant was introduced to portions of the county. The Woodlands uses a mix of 65% groundwater and 35% surface water, he said in late April.

Stinson said studies have shown previously diminishing water levels in the Jasper and Evangeline aquifers used in the county stabilized once groundwater use was reduced, and almost no fault movement was measured. He said he is concerned the newly proposed DFC could negate those benefits because it allows for more annual groundwater use.

“This positive environmental data was recorded with groundwater withdrawal capped at about 64,000 acre-feet per year. I am concerned that implementing the new DFC with a much higher groundwater allocation—97,000 acre-feet—will negate those positive environmental findings.”

An acre foot is the amount of water that would cover an acre 1 foot deep, or 325,851 gallons, according to the Texas Water Development Board.

Stinson said he felt a more reasonable approach would be to start with the lower groundwater allotment and allow increases over time while tracking subsidence, aquifer levels and fault activity.

At an April 27 presentation at a One Water Task Force meeting, Mike Turco, general manager of Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, which provides groundwater regulation and monitors subsidence, said subsidence activity appears to have ticked up in The Woodlands area over the past several years after dropping when less groundwater was extracted.

Changing priorities

According to Texas law, landowners own the water underneath their properties, and groundwater conservation districts must ensure regulations do not infringe on an entity’s or individual’s right to pump groundwater.

Groundwater conservation districts must walk a tightrope protecting individuals’ right to pump groundwater as well as the rights of those affected by others’ pumping, said Gregory Ellis, an attorney who represents Texas groundwater conservation districts and subsidence districts.

“You’re really always talking about property rights versus property rights,” Ellis said. “You have the property rights of the person who has the well ... [and] you have the property rights of the people who want to keep their land above sea level.”

In The Woodlands, some residents claim their properties are being damaged from subsidence and fault line activity, which have both been linked to excessive groundwater withdrawals.

“Property rights to me means the right to ... not have my foundation crack or my house subjected to flooding,” The Woodlands resident Carolyn Newman said.

Rieser said the issue affects not just individual property owners but the area’s entire business base.

“I think it’s important that everybody understands that The Woodlands’ tax base is $22 billion, and it’s acutely important to this county,” Rieser said. “Everybody should be mindful of what they do that could potentially impact that tax base.”

However, Hardman said the property rights of a few individuals cannot be the basis for groundwater decisions for the entire county.

“The people in The Woodlands have to weigh what’s more important to them: Having a higher water bill and not having subsidence or ... a reasonable amount of subsidence [and] keeping your water bills more affordable,” Hardman said.

Concerns about subsidence in The Woodlands have led in part to the formation of its One Water Task Force—which last year broadened the mission of a former drainage task force to include groundwater usage concerns.

Among other topics, the task force has suggested funding the installation of a extensometer into the Jasper Aquifer to measure subsidence and have a clear indication of whether it is happening at a higher rate than expected in The Woodlands.

Rieser said this information would help The Woodlands-area entities determine a path forward, regardless of the final form the DFC takes.

“I was a subsidence skeptic, but there is way too much evidence out there that I’ve seen with my own eyes ... and we can’t just ignore it,” Rieser said. “Is it imminent? No, but it is a long-term risk that needs to be addressed.”