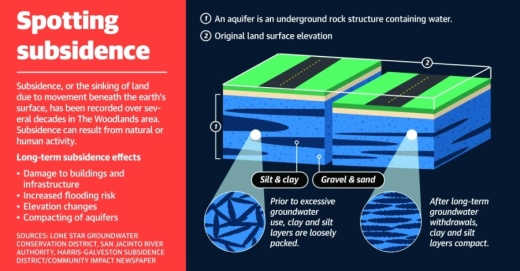

These entities are examining the future of groundwater usage ahead of a regional decision on new long-term groundwater usage rules that must be adopted in early 2022. However, officials and experts disagree on how much groundwater Montgomery County should be allowed to pump and how much subsidence—the gradual sinking of the land that can be caused by groundwater overuse—is acceptable as a result.

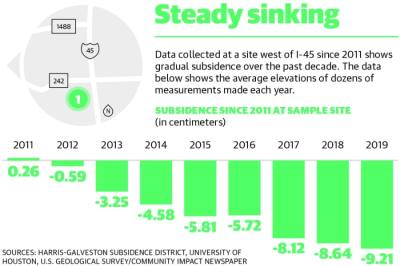

Hydrologists widely agree excessive groundwater pumpage can result in subsidence, which can lead to flooding and infrastructure damage as well as exacerbating the activity of fault lines—cracks in the earth’s crust. Subsidence is more heavily concentrated in southern Montgomery County, with some areas in The Woodlands recording a subsidence rate of just over 1 centimeter per year, according to data from the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District.

“You can’t undo subsidence,” said Jace Houston, the general manager of the San Jacinto River Authority, which provides surface water in Montgomery County. “Once the ground sinks an inch, you can’t make it come back.”

A new set of guidelines approved in September could allow for increased groundwater withdrawal, and new conditions for groundwater resources in the region will be decided in 2021. But as those parameters remain under discussion, a study funded by The Woodlands Township in cooperation with The Woodlands-based Houston Advanced Research Center is examining links between groundwater use and subsidence, which HARC hopes will help inform future decision-making.

“Everyone needs that water, and as a community we have to work together to figure out how to use it best not just for today but for the future,” said Stephanie Glenn, the program director of hydrology and watersheds at HARC.

Governing groundwater

Rules regarding water usage are overseen by several regional and local entities. Montgomery County is home to the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District, which regulates groundwater countywide. It is also a member of the 20-county Groundwater Management Area 14, which is composed of two subsidence districts and five groundwater conservation districts, including the LSGCD.

To reduce the county’s reliance on groundwater, many large-volume groundwater users in Montgomery County entered into an agreement with the SJRA in 2015 for the SJRA to provide surface water to certain entities using a $497 million surface water treatment plant on Lake Conroe and water pipe transmission system paid for by the entities.

Limits on groundwater use were also previously set by the LSGCD board with a long-term mandate for large-volume groundwater users. The plan required the reduction of groundwater usage to 70% of their 2009 totals beginning in 2016. However, guidelines set by the LSGCD and the SJRA have been disputed in recent years as water rates increased, including a 2015 lawsuit brought by the city of Conroe and other entities aimed at loosening LSGCD limits on groundwater usage.

In 2018, a judge declared the reduction rules void and unenforceable. To comply with the judge’s ruling, the LSGCD was required to adopt new rules and a new groundwater management plan. The LSGCD adopted new rules in September, raising pumping limits for groundwater, which district officials claim puts the LSGCD more in line with state law.

Jim Stinson, the general manager of The Woodlands Water Agency, said The Woodlands municipal utility district management agency has limited its annual water usage mix to 35% groundwater and 65% surface water under earlier LSGCD rules. With those rolled back, Stinson said it is likely municipalities outside The Woodlands that shifted to surface water use in recent years could return to more groundwater usage due to its lower cost and ease of delivery.

Stinson said he believes the new rules will adversely affect the county based on data showing reducing groundwater withdrawal could minimize fault movement and subsidence.

“The new LSGCD rules place Montgomery County in the crosshairs of a critical decision on the future of groundwater: Should groundwater be managed on a regional basis that has widespread public benefits? Or is groundwater a private property commodity where everyone, including individual landowners and for-profit water companies, have pumping rights that adversely impact others?” Stinson said.

New rules on tap

A planning committee of GMA 14, the regional body managing the Gulf Coast Aquifer System that provides groundwater in Montgomery County, is set to meet in late February to discuss the desired future condition, or DFC, for the aquifers—underground rock structures containing water—beneath Montgomery County and neighboring counties.

LSGCD is considering three scenarios for the new DFC based on different levels of groundwater pumping—ranging from 61,000 to 115,000-plus acre-feet of groundwater pumpage per year. One acre-foot of water is equal to 325,851 gallons and can support six Texans’ water usage over one year, according to the Texas Water Development Board.

Models predict subsidence of anywhere from 0.25 to 2.5 feet at points throughout Montgomery County over the next six decades, and all three scenarios used 1 foot of subsidence as a modeling constraint.

LSGCD General Manager Samantha Stried Reiter said the district is one of a few within GMA 14 to have its own subsidence-measuring devices, and she believes all representatives of area entities are concerned with future subsidence. However, LSGCD officials said they are not concerned about the level of estimated subsidence projected by their DFC scenarios.

“The model scenarios did not predict unacceptable levels of subsidence in Montgomery County under any of the scenarios we are considering. The district has supported subsidence studies historically and is currently in the middle of another subsidence study,” Reiter said in an email.

Reiter said she believes crafting a balanced DFC would not necessarily require either an exclusive focus on property rights or total protection of aquifer resources.

“You can still be concerned and study aquifer conditions but that doesn’t necessarily translate to zero increases particularly if the science shows you are on track with [the] DFC. ... Our best available data, science and rules support additional production by the permit holders,” she said.

While the regional water districts consider what role subsidence concerns should play in the crafting of future pumping goals, the process has already been recorded to varying degrees throughout Montgomery County.Several data points monitored by the University of Houston and H-GSD in The Woodlands have shown consistent subsidence in the past decade. A site south of St. Luke’s Way west of I-45 has sunk at a rate of more than 1 centimeter per year since mid-2011, while several sites in Cochran’s Crossing have fallen between 0.53 and 0.8 centimeters per year since 2014-15.

Action in The Woodlands area

The potential effects of groundwater withdrawal on subsidence and fault line activity have prompted The Woodlands Township to take action.

The township’s partial funding of a $120,000 Groundwater Research Consortium and Science Advisory Committee with HARC, which Glenn said would act as a “peer-reviewed body” to examine data and produce reports related to groundwater usage, was approved by the township board last July ahead of the group’s formation in August.

The township’s Drainage Task Force was also renamed the One Water Task Force in October in response to the scope and complexity of water issues in the area.

The topics of water use and subsidence are significant in The Woodlands, officials said, because several areas of subsidence activity have been identified in south Montgomery County, and several fault lines run through the area, which also is subject to flooding along Spring Creek.

“If we go back to going ahead and pumping indiscriminately, we have ample evidence in The Woodlands of subsidence triggering additional fault activity in areas of Panther Creek and Cochran’s Crossing, and that’s worrying,” said Bruce Rieser, who chairs the One Water Task Force and is also vice chair of The Woodlands Township’s board of directors.

As of its Jan. 27 meeting, the board of directors agreed to send letters to the LSGCD and GMA 14 to register its concerns about changes to the groundwater withdrawal rate. Chair Gordy Bunch said at the meeting he wanted to recommend changes be slow, measured and monitored.

He also noted his personal experience with what he described as the effects of subsidence and fault line activity on a home he owned, which he claims cost him $1 million in damage, including extensive cracks in the house and pool.

The topic has also engaged residents. Mark Unland, who called into the Jan. 27 board of directors meeting, said he was concerned about the many layers of government that subsidence planning has to navigate as well as its relation to flooding.

“It is a slow-motion train wreck,” Unland said. “It’s going to take decades for this to ultimately pan out. ... We have two arms of government, [and] one arm is making decisions, which could make subsidence worse, which could make flooding worse.”

Rieser said one compromise could be a 50-50 mix of groundwater and surface water, which would help to keep the surface water treatment plant in Conroe solvent while minimizing subsidence.

Bunch said he has subsidence measured at his property every six months. He said subsidence effects seemed to slow when surface water entered into the local water mix, and he believes a measured approach to incorporating groundwater usage would be effective.

Joe Sherwin, Oak Ridge North’s public works director, said the city—which sources its water from two groundwater wells and Lake Conroe’s surface water—continues to monitor potential subsidence as well.

“The development of sustainable water resources is vital as the community grows, and declining water levels in the aquifer will be an issue for all communities in Montgomery County to address together,” Sherwin said in an email.

Eva Vigh contributed to this report.